Not everyone respects that right. But the Wampanoag are determined to continue, saying their work is an essential expression of 12,000 years of heritage, sovereignty, and lifeways.

Not everyone respects that right. But the Wampanoag are determined to continue, saying their work is an essential expression of 12,000 years of heritage, sovereignty, and lifeways.

August 21, 2024

Freshly caught and harvested quahog clams from Cape Cod.

This is the first of a two-part series.

On a recent spring afternoon, CheeNulKa Pocknett’s truck rattled slowly across Monomoscoy Island, the engine roar swallowing the caw of seabirds. It caught the attention of a gray-haired woman working in her garden who popped up from behind a wall of red and yellow tulips, a scowl shading her face.

“She knows me and doesn’t like me,” Pocknett said, casting a half-hearted wave in her direction. Pocknett, a member of the Wampanoag tribe, is a regular here on Mashpee’s Little River, a stretch of Cape Cod ringed by multi-story homes, each with its own private dock. He knows all the good fishing spots—or at least, what were once good fishing spots—along the murky perimeter.

Pocknett steered down a gravel driveway and parked between two wind-worn wooden houses, unfurling his 6’7” frame from the driver’s side, boots first. He hefted a 50-pound rake and stack of plastic baskets from the bed of his truck and tramped toward the river, ignoring the “private property” warnings staked around the backyard. Like his ancestors for 12,000 years, he had come to this river in search of a hard-shelled clam known as a quahog, and no amount of anti-trespassing signs could keep him away.

“They’re preventing us from practicing our culture, our right of ways, our livelihood.”

Pocknett sloshed through the shallows, waders dredging up brown clouds of mud. “This is nothing like ‘black mayonnaise,’” he said, referring to other areas where once-sandy bottoms are now thick sludge. “Here it’s actually not so bad.”

Low-lying Mashpee is carved from water: from mosquito-bogged marshes, pine-shrouded ponds, and rivers that wind in brackish ropes past condos and golf courses. Since the 1970s, much of the town’s waterfront has been privatized and developed by nonmembers of the Wampanoag tribe.

The manicured and serene landscape above the waterline belies tremendous damage below, where shellfish and finfish have thinned—and in some cases disappeared—due to nitrogen pollution emitted from multi-million–dollar developments and their septic tanks. Stripped of land and resources, a dwindling group of Mashpee’s Wampanoag is committed now more than ever to asserting their rights to hunting and fishing.

The Monomoscoy Island beach on Mashpee’s Little River, where CheeNulKa Pocknett frequently digs for wild quahogs (pictured right), with a private dock that extends into the water. (Photo credit: Emma Glassman-Hughes)

These “Aboriginal rights,” as they’re legally known, are reflected in treaties between the U.S. and sovereign Indigenous nations, and grant unlimited harvests, even from private property. But not everyone on Cape Cod respects these rights, sometimes resulting in screaming matches and 911 calls. Wampanoag fishers, like Pocknett, are forced to shrug it off. Their work, they say, is to both triage a dying ecosystem and continue an essential expression of their heritage, sovereignty, and lifeways.

Under the April gloom, Pocknett waded deeper into the river, the current pulling at his knees. With a grunt, he plunged his rake into the water and dug in.

For thousands of years, the Wampanoag—the “People of the First Light”—have harvested fish for food, trade, art, and fertilizer. A shellfish farmer as well as a fisherman, 39-year-old Pocknett can trace his lineage on these Atlantic shores well into the past, before poquauhock, in Algonquin, became “quahog,” before his ancestor, Massasoit, would be known as the first “Indian” to meet the pilgrims, and long before federal recognition (won by the Wampanoag in 2007) held any meaning for the Indigenous nations of this continent. For most of that time, the Wampanoag stewarded a thriving waterway.

When he isn’t raking for wild quahog, Pocknett manages the tribe’s shellfish farm, using modern aquaculture practices that are a footnote in the Wampanoags’ millennia-old relationship to the waterways of the Cape. Generations before Pocknett’s great uncle founded the First Light Shellfish Farm on Popponesset Bay, in the 1970s, Pocknett says it’s likely the tribe cultivated bivalve species and maintained the shallows with ancient clam gardening techniques, constructing “reefs” out of rocks in the sandy bottoms of the bays and rivers. The abundant eelgrass that once grew in those same waters fostered eels, scallops, and fish species like striped bass, all important elements of the Wampanoag diet, culture, and worldview.

CheeNulKa Pocknett reached down to grab the handle of a 50-pound bull rake used to dig quahogs on the Monomoscoy Island beach along Mashpee’s Little River. (Photo credit: Emma Glassman-Hughes)

The natural abundance of the bay, however, has been severely diminished by development and nitrogen pollution. Today, Pocknett and his cousins receive funding from U.S. Fish and Wildlife to raise the tribe’s quahogs and oysters in that pocket of the Popponesset, a small body cradled on the Cape’s southwestern arm. Instead of clam reefs, the farmers use oyster cages and clunky steel rakes to manage their crop.

This helps the local ecosystem somewhat, as shellfish remove nitrogen from the water by absorbing small amounts into their shells. But the eelgrass is already gone from this bay, as are most of its wild fish. And First Light is not nearly big enough to replace what’s been lost, Cape-wide.

Off the farm, other bays and rivers that sustained past generations with abundant wild shellfish have been radically transformed, too. Areas that were once quahog hotbeds are now so mucky from nitrogen-fed algae that they’re inhospitable to growth. Aboriginal rights allow Wampanoags to cross public and private land to fish, but they don’t guarantee that there will be any fish in the water once they arrive.

Those sites that remain viable have limited fishing access. Many have been blocked by private developers, fences, or overgrown brush. But there are psychological deterrences, as well. The prospect of aggravated non-Indigenous neighbors is enough to keep some Wampanoags out of the water.

One of Pocknett’s cousins, Aaron Hendricks, worries that for Wampanoag youth, the once-proud practice of fishing is now entangled with shame. He recently recalled a day from his childhood when he was about four. His Aunt June took him fishing in Simons Narrows, down a dirt path that had previously “always been a way to the water.” A strange woman burst out of the property, “cussing, yelling, screaming that you can’t park here.”

Now 42, Hendricks has his own children to teach—except instead of taking the well-worn paths “my people showed me as a puppy,” he said, they sneak through “a briar patch and a thousand mosquitoes and poison ivy” to avoid confrontation. “Half the kids don’t even want to go because they hear the stories,” he said. “I don’t want to show them that. It scars them, type shit.”

Pocknett’s fishing trips can also devolve into ugly confrontations, pitting his tribe’s ancient claims to fishing grounds against the rights of property owners in newer developments. Pocknett often live-streams these encounters on Facebook, as he did four years ago, when a homeowner reported him and his brother for trespassing on a Monomoscoy Island driveway.

In that encounter, Pocknett accused the Mashpee police and natural resources officers of impeding his rights. In the footage, Pocknett’s voice throbs with rage: “We fish every day, they don’t care. They tell us that we’re nothing but a bunch of dumb Indians.” When asked about the incident, he was only slightly more measured. “They’re preventing us from practicing our culture, our right of ways, our livelihood,” he said.

The beach at Punkhorn Point on Popponesset Bay, where the First Light aquaculturists load their boats. (Photo credit: Emma Glassman-Hughes)

Such confrontations are likely to continue. As of April, the tribe has 321 total acres of reservation land, designated by the Supreme Court when it ended a protracted legal battle that began in 2015. All but one of those acres, however, are landlocked. To fish as they’ve always fished, Wampanoags have no choice but to assert their Aboriginal rights on private property. So, Pocknett walks through yards.

Not everyone in Mashpee respects the rights of the Wampanoag. Non-Indigenous officials have historically misunderstood these rights—or ignored them. In recent years, for example, the local Shellfish Commission began discussing tribal fishing rights in its monthly meetings at the Mashpee Town Hall. Minutes from a January 2019 meeting note: “Can anyone pass through private property based on the colonial ordinance? It is still unknown.”

A few months later, minutes show that the commission discussed a statement issued by Wampanoag police claiming the tribe “has the right to access water to fish through any property.” The Commission’s response was firm: “The town manager has notified both the police and the tribal council that this is not where the town of Mashpee stands,” those minutes say. “No-one [sic] can access the water through private property.”

“Putting up a bunch of fences and denying somebody access to a parcel of land or water that they have a property interest in” goes against fundamental rules of law.

Legal experts on Indigenous affairs disagree. A landmark 1999 appeal in the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court favored the Mashpee tribe’s extensive Aboriginal rights and forever clarified the state’s stance, according to a New England–based lawyer who is working with the tribe on current litigation and asked not to be named to avoid appearing biased.

The 1999 case, Commonwealth v. Maxim, determined that Aboriginal rights supersede a town’s shellfish bylaws, which set rigid standards and limits for non-Indigenous hunting and fishing. The decision relied primarily on protections outlined in the Treaty of Falmouth, signed in 1749.

Other cases, including the 1974 “Boldt Decision” in Washington State, have firmly set legal precedent for sovereign fishing rights. In Massachusetts, in 1982, the state House of Representatives adopted a resolution recognizing “the ancient and aboriginal claim of Indians” to “hunt and fish the wildlife of this land for the sustenance of their families.”

Matthew Fletcher, director of Michigan State University’s Indigenous Law and Policy Center and member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, spent seven weeks as a visiting professor of Federal Indian Law at Harvard Law School this spring and sits as a judge on the Mashpee tribe’s appellate court. In an interview, he said anyone who claims Wampanoag fishing rights are unclear is willfully overlooking decades of precedent. Aboriginal fishing rights are property rights and should be understood as such, he said.

“Putting up a bunch of fences and denying somebody access to a parcel of land or water that they have a property interest in” goes against fundamental rules of law, Fletcher said. The property interest of the Wampanoags in this case is their Aboriginal fishing right, which extends to those lands and waters.

“Under every rule of law, going back to England before there was the United States, people have a right to access, within reasonable limits, other people’s property in order to get to their property,” Fletcher said. “You learn that in the first year of law school. And Indian people are denied that basic right every single day.”

The denial of rights in Mashpee can be subtle, as with “No Trespassing” signs, or overt, as when local homeowners involve police. Attitudes vary, but the town is marred with distrust.

On a summer day at Mashpee Neck Marina, I took a walk down a residential street crowded with large homes, each with a neatly trimmed yard and picture windows looking out on the Santuit River, where a fleet of chrome yachts and speedboats winked under the midday sun. At one home, I met a seasonal resident named Kathy, who declined to give her last name, but said she tries to keep Wampanoag fishers from crossing her yard. She and her husband had stapled “No Trespassing” signs to the pitch pines that gird a narrow path from the front of the house to the river in the back.

“They’re tribal people, and they carry buckets down there and take oysters in bulk,” Kathy said, standing in her doorway, a small dog drooped over her feet. “They think they own the land. They think it’s theirs.”

Nearby, in another doorway, an older man said the Wampanoag have “always been respectful” of him and his property. His wife, who joined him at the door, was less amiable. “We won’t say anything about the Wampanoags in any newspaper,” she said angrily, motioning for her husband to come inside. “We don’t want any trouble,” she said, then slammed the door.

In late September, a row of sullen three-story homes stood guard over the Mashpee River, flat as a sheet of glass. Down a gravel path, the beach at Punkhorn Point bid its quiet farewell to summer, the sand populated now by a large blue crab, belly-up in surrender, and a silent procession of fiddler crabs creeping through tufts of beachgrass.

Nearby, Pocknett measured out bolts of hazard-orange mesh, a cigarette affixed to his bottom lip. He pulled a few bull rakes from his truck and dragged them to a small motorboat in a clatter of steel, tossing them in the boat along with plastic baskets, a coil of rope, and enough cigarette packs for each of his three cousins, who had also come to work.

In 2022, the tribe was awarded an aquaculture grant of $1.1 million through the Economic Development Administration, part of the American Rescue Plan’s Indigenous Communities program. The cousins were preparing for the arrival of Pocknett’s uncle, Buddy, who was driving in with a truckload of baby quahogs. They would plant the clams out near a sandbar in Popponesset Bay, knowing that each mollusk would clear out some nitrogen, if only a little, as it grew.

Two million baby quahogs sat in sacks in the back of Vernon “Buddy” Pocknett’s truck, ready to be seeded into the Popponesset Bay off Punkhorn Point. (Photo credit: Emma Glassman-Hughes)

When Buddy arrived, the men transferred a dozen sacks containing 2 million baby quahogs into the boat, and cast off for where the murky water ran clear.

Here, Pocknett dropped anchor. The men disembarked, water up to their knees. A couple of them set the mesh in a giant rectangle in the bed of the bay, then sprinkled the tiny shellfish over the water like seeds. As his cousins scattered the new crop, Pocknett attached a rake to his waist with a rusty chain and shuffled to the side a few feet to dig for larger clams. The rake’s cage allowed small clams to slip through the bars, giving the next generation a chance to grow.

In legal terms, the Mashpee tribe’s traditional hunting and fishing rights are protected acts of “sustenance.” The state understands that to mean pure calories. But Fletcher, of Michigan, argues the Indigenous interpretation honors full livelihood. “It is deeply cynical and cramped for non-Indians to say sustenance is merely calories,” he said.

To Pocknett, true sustenance means much more. Out on the sandbar, he leaned back 45 degrees, driving his rake into the mud with coordinated thrusts of hips and arms. Sustenance means to “provide life,” he said. “Not just food.”

September 4, 2024

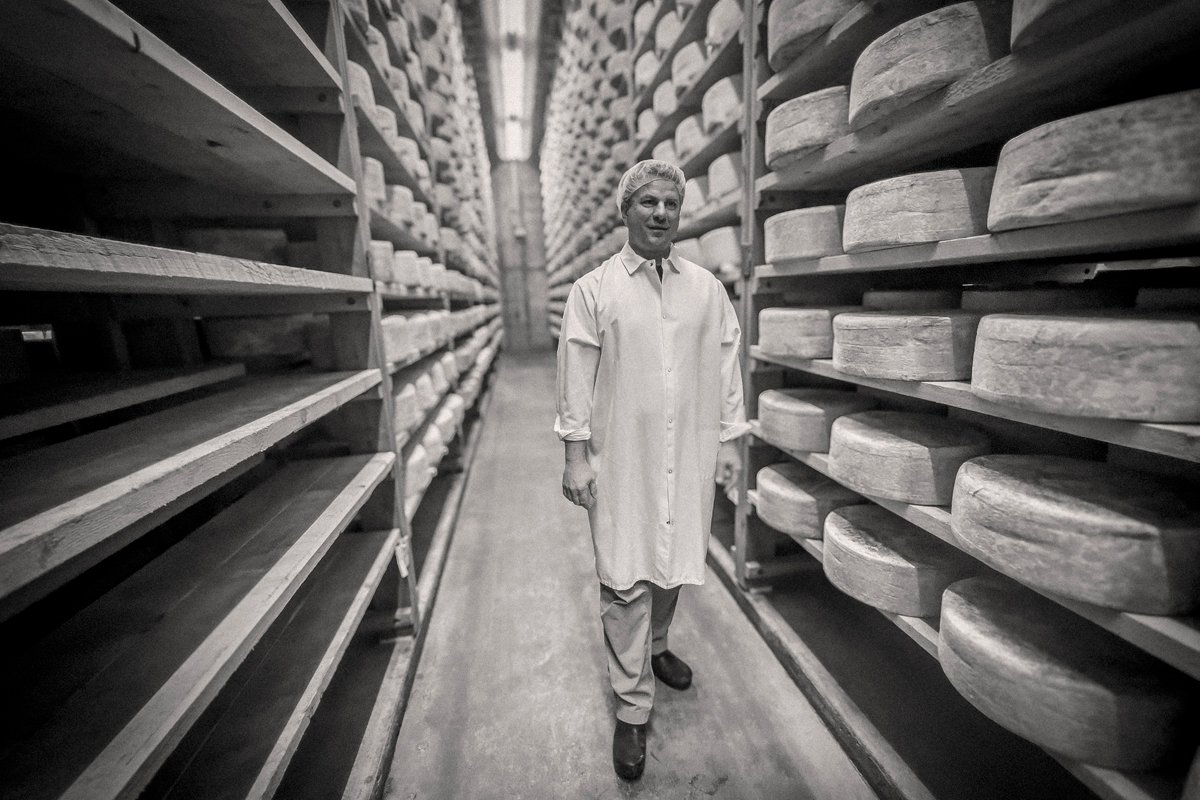

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Two unexpected trucks with 4 people (2 men, 2 women) come onto private property, smoking, joking — 3 of the 4 doing nothing at all of an indigenous nature. Owner? Perhaps the elderly owner lives alone, feels security and safety seems shattered. Perhaps has lived 60+ years there in a small home. Not rich. Unlimited access to whom and when, like at night, a group — dig for a clam and bring your friends. Unproductive broken shells littered around to cut bare feet. No control for one’s own peace and security and safety. And by the way, perhaps the owner is an avid proponent of indigenous people’s rights, but feels threatened by the aggressiveness and confrontation of prepared anger, ranting and videoing.

Not a simple one-sided situation. Journalistic Perspective, please.