The PBS documentary ‘One with the Whale’ explores the importance of subsistence hunting and gathering in a Yupik village—and what happens when mainlanders misunderstand it.

The PBS documentary ‘One with the Whale’ explores the importance of subsistence hunting and gathering in a Yupik village—and what happens when mainlanders misunderstand it.

April 22, 2024

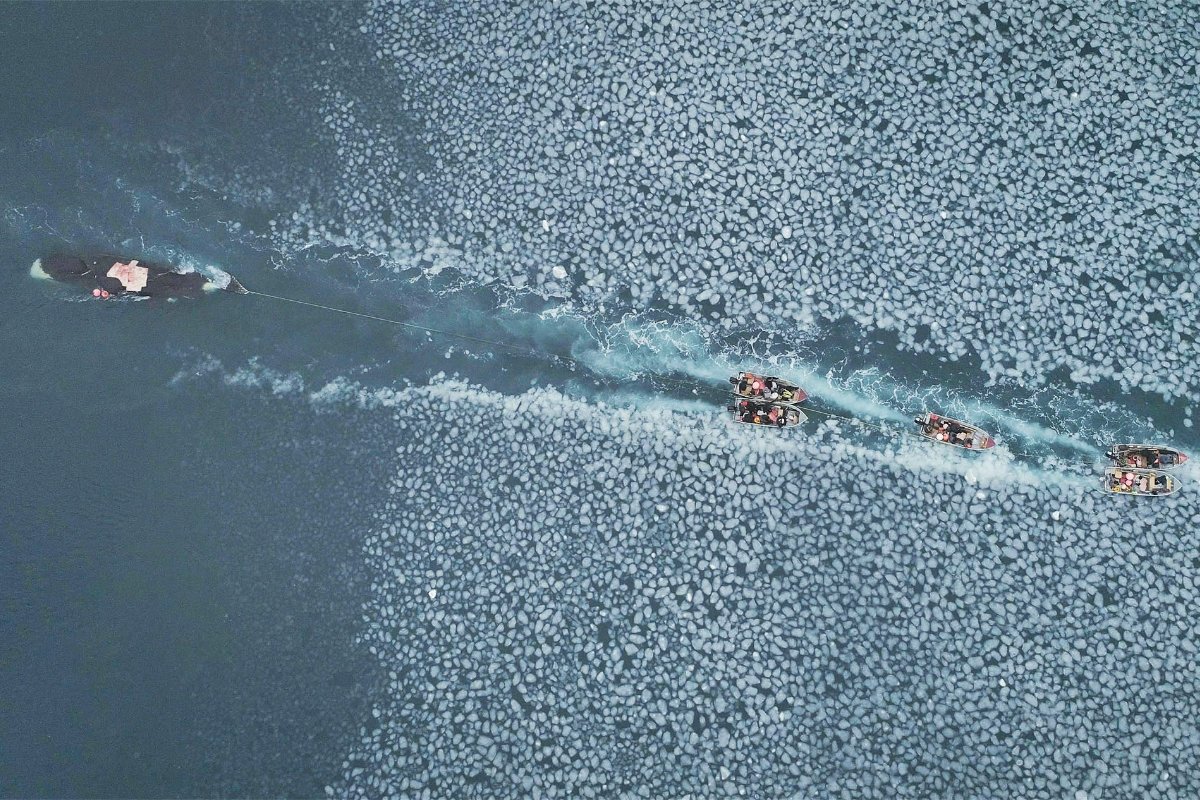

Hunters parting the ice as they tow the whale back home. (Photo credit: Jim Wickens)

For many Alaska Native communities, subsistence hunting and fishing is a way of life. For the Apassingok family, it accounts for more than 80 percent of their food. If Daniel Apassingok and his sons, Chris and Chase, have a particularly fruitful day out on the water pursuing seals, walruses, and whales, they can feed their entire Siberian Yupik village of Gambell.

So it was a collective victory for the village in April 2017, when then-16-year-old Chris became the youngest person in his community to harpoon a whale: Gambell fed off the bounty for months. But after his mom, Susan, posted about the exciting accomplishment on Facebook and the Anchorage newspaper picked up the news, the family received thousands of online hate messages—even death threats.

At once heartbreaking and heartwarming, this story is the subject of One with the Whale, a new, award-winning documentary that premieres on PBS’s Independent Lens on April 22. Created by co-directors Pete Chelkowski and Jim Wickens with the community’s blessing, it showcases the struggles of subsistence hunting—and the lack of understanding about its importance.

“Subsistence hunting is a traditional lifestyle that’s been passed down from generation to generation, and we rely upon it dearly,” says Daniel Apassingok. “It helps feed not just the community, but the next village and people all over the state.”

With a population of around 600 people, the remote town of Gambell sits on the northwest cape of St. Lawrence Island within the Bering Sea, closer to Russia (36 miles) than the Alaska mainland (200 miles). The environment there is rugged and barren, lacking trees or other vegetation. Conditions can be harsh, with temperatures dropping to -20°F in the winter.

For Chelkowski and Wickens, who are not Indigenous, making this film had a profound impact on their understanding of Alaska Native lifeways. “I’m from New York City, and there are probably more people living in the building I grew up in than in the whole village of Gambell—so witnessing the way of life in Gambell was really eye-opening,” says Chelkowski “But this is not some fairy tale; these are real people who are living in the most difficult conditions on the planet and overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles. And they do it with hope and love.”

In Gambell, packaged foods and other supplies arrive only by plane, and the inflated prices at the local grocery store reflect those import efforts. For their family of five, Susan spends upward of $500 a week on the mainly processed foods that line the store shelves. Compounding matters, a lack of jobs makes it tough for many Gambell residents—whose poverty rate hovers around 35 percent—to afford those high food costs.

“You have to hunt, you have to gather berries, you have to gather sea vegetables,” former John Apangalook School principal Rob Taylor explains in the film. “If you don’t do subsistence activities, you die.”

“You have to hunt, you have to gather berries, you have to gather sea vegetables. If you don’t do subsistence activities, you die.”

The school allows students to miss 10 school days per year for subsistence hunting and gathering, though kids often skip out on more than that in order to put food on the table. Given the imperative of providing for their families, it can be tough to impress upon young people the importance of formal education.

Of particular significance is the springtime bowhead whale migration, which kicks off a weeks-long whaling season starting in late March or early April, when temperatures warm up to 20°F. Apassingok recalls some seasons, like last year’s, when they didn’t catch any whales. In those years, they try to make up for the lost harvest by catching more seals and walruses throughout the spring and summer. But whales—particularly bowheads, one of the largest and heaviest species—are the ultimate prize. Each can yield hundreds of pounds of meat and maktak (skin with blubber), which are rich sources of lean protein, healthy polyunsaturated fatty acids, and vitamins A, D, and E.

Gambell is one of 11 Alaska villages that participate in whaling as authorized by the International Whaling Commission and regulated by the nonprofit Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission, which oversees the quota system. The estimated 50 whales harvested by Alaska Native communities annually provide about 2 million pounds of food, which would cost upward of $20 million to replace with a store-bought protein such as beef, which averages anywhere from $10 to $20 per pound in these remote places.

“A small 30-foot whale will feed a family for a few weeks,” says Apassingok. “If you catch three whales, you can feed a family for the summer. Some people can’t afford to buy their food from the stores, especially when they have big families.”

The Yupik way of life is threatened by climate change, which is causing extreme weather, flooding, coastal erosion, and unprecedented ice loss across the Bering Sea. Those evolving conditions, in turn, have been shown to impact algae, zooplankton, fish, and seabird populations in recent years.

In addition to addressing food security concerns, whaling is also an important cultural tradition that has been practiced by Siberian Yupik peoples for thousands of years. Apassingok remembers going on his first hunting excursion at 5 years old. His son Chris started hunting seals at age 7, then at 15 became a striker—the hunter posted at the front of the boat during harrowing whaling outings. In Gambell, many of these customs have been well-maintained as a result of its isolated locale, far from modern-day influences.

The traditional and modern worlds collided back in 2017 after news spread of Chris’s rite-of-passage harpooning of a 200-year-old, 57-foot bowhead whale. When Canadian-American environmentalist Paul Watson heard about it, he took to social media.

“Some 16-year-old kid is a frigging ‘hero’ for snuffing out the life of this unique, self-aware, intelligent, social, sentient being,” the now-deleted Facebook post read. (The quote is preserved in a High Country News article from the time.). “But hey, it’s OK because murdering whales is a part of his culture, part of his tradition. . . . I don’t give a damn for the bullshit politically correct attitude that certain groups of people have a ‘right’ to murder a whale.”

That inflammatory post prompted Watson’s followers—and countless other keyboard warriors—to troll the Apassingok family. Thousands of negative comments flooded in, sending the shy and stoic Chris on a downward spiral that nearly prevented him from graduating from high school.

But the community rallied around him, as did many prominent Alaskans. Governor Bill Walker presented Chris with a certificate “in recognition of his skill and expertise in landing a bowhead and receiving the gift of the ancient whale’s life to sustain his people, and upholding the values and traditions of Alaska Native culture despite opposition.” U.S. Senator Dan Sullivan also recognized him as “Alaskan of the Week” on the Senate floor then went on to hold a Commerce Committee hearing about the importance of whaling in Alaska.

“Our traditional lifestyle should be understood like a job or any other livelihood. With this film, we’re trying to help the world understand why we do this for a living.”

In October 2017, Chris was tapped to give the keynote speech at the Elders and Youth Conference, which preceded the notable Alaska Federation of Natives conference. “We take care of our land and ocean as they take care of us,” he said. “The biggest rule we are taught by the elders is to never become discouraged while hunting in hard situations. Even though we almost die, we must never give up. We must be prepared for any situation. We must know how to foretell the weather ourselves as our ancestors did. We must never be discouraged by any accident or anybody who may threaten us. I am part land, I am part water, I am always Native.” He then called upon attendees to join him in upholding traditional sustenance activities.

Seven years after that distressing situation, Chris and his family are both excited and anxious about having their story told to mainstream audiences. Naysayers will inevitably surface, especially as the documentary’s timing coincides with a call from Polynesian Indigenous groups to grant whales legal personhood as a protective measure. But the Apassingoks and the filmmakers hope that One with the Whale impresses upon viewers the vital role that whaling plays for Yupik peoples.

“The misunderstanding I see [about subsistence hunting] is beyond my imagination,” says Apassingok. “Our traditional lifestyle should be understood like a job or any other livelihood. With this film, we’re trying to help the world understand why we do this for a living.”

Chelkowski hopes the documentary inspires empathy among non-Native viewers, much like making the film did for him. “Subsistence hunters in Alaska are not only one with the whale; they’re one with nature,” he says. “They have co-existed beautifully with these animals for thousands of years. Without the whale, they can’t survive. In the end, the whale symbolizes tradition, love, and family.”

“One with the Whale” premieres on PBS’s Independent Lens on April 22. Watch the trailer below.

Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article misspelled the name of the Siberian Yupik people. We apologize for the error and appreciate the readers who alerted us to the mistake.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.