In his new book, Chris Smaje argues against lab-grown meat and ecomodernism and champions a future where more people return to rural areas to rebuild local economies.

In his new book, Chris Smaje argues against lab-grown meat and ecomodernism and champions a future where more people return to rural areas to rebuild local economies.

November 15, 2023

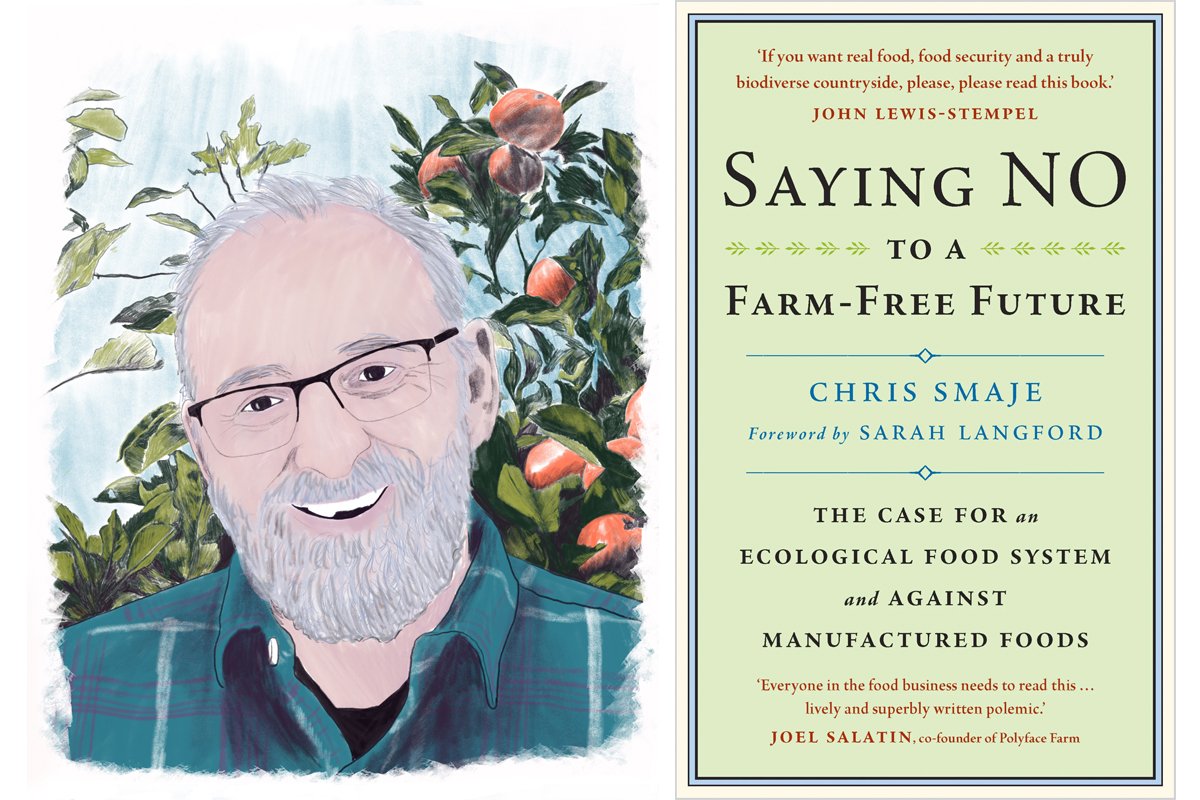

Photo illustration: Nhatt Nichols

Imagine a future where humans live entirely in cities in an attempt to minimize their impact on the natural world. Meat is made in factories and grazing is a thing of the past.

This is not a world Chris Smaje wants to live in. The writer, farmer, and social scientist doesn’t believe that humans need to take themselves out of the natural world to protect it, and he argues for agrarian localism over ecomodernism in his latest book, Saying No to a Farm-Free Future.

Ecomodernists believe that it is possible to protect nature and lessen the environmental impact of human development primarily through technological advances. This is achieved by shifting our development away from the natural world. Agrarian localists like Smaje argue that we can’t separate people from nature, and instead we should focus on reducing our impact by working more directly with our local environments: farming at a smaller scale, incorporating rewilding principles into our farming practices, and relying more on human power than internal combustion.

“Plenty of people are figuring out farming that works for them locally in most parts of the world; there’s an Indigenous tradition of land use that we can build on.”

The book is, at the core, a rebuttal to George Monbiot’s book, Regenesis: Feeding the World Without Devouring the Planet. But it’s also much more than that. After his public response to Monbiot’s book elicited a response from readers, Smaje saw an opportunity to write about the role of farming, grazing, and rural places in an increasingly unstable and unpredictable future.

Smaje is a passionate and wryly funny writer. About his initial reluctance to wade into the debate he writes, “There’s something to be said for not . . . ‘paddeling the douchecanoe’ by rising to the bait of ecomodernist provocations . . . Once the veil is removed, what’s left is . . . well, basically just shrill activism and hippy dreaming with a high-tech gloss.”

The book advocates for doing less and doing it more thoughtfully at a time when humanity’s biggest challenges are often being addressed using more tech, more capital, and more emphasis on the role of cities. Smaje champions a future where more people return to rural areas and emphasizes small farms’ role in supporting local economies, healthy environments, and stronger relationships between people and animals.

He writes: “Our societies must turn to low-energy, low-capital, low-carbon agroecological approaches geared to meeting local needs primarily from local land, air and water. . . . Agriculture at its best can do this.”

Civil Eats spoke with Smaje recently to discuss his book, the role of farms in the future, and his view of humans as a keystone species.

While reading your book, I had this image of you sitting down and reading George Monbiot’s book and then furiously typing into the night.

I connected with George in 2015 after the Ecomodernist Manifesto was published. I wrote a critique of it that he read and was very enthusiastic about. He wrote an article in The Guardian critiquing ecomodernism. He mentioned my article, so he gave a boost to my writing, which I appreciated at the time. But gradually, he’s drifted into a position indistinguishable from ecomodernism.

He has been pretty much the only journalist with a mainstream media platform who has been a radical, progressive, green voice, so it matters what he says. He hasn’t written much about food and farming in recent years; this was his big food book. And it’s very, very problematic. I wrote a review on my blog and got into a Twitter argument with him about it. My publisher picked up on that, and almost before I knew it, I had signed a book contract.

I want to move on to making a case for agrarian localism and not be Mr. Anti-George Monbiot, but one of the issues is his book emphasizes how much [his case for lab-cultured meat] is grounded in the science and the data and a lot of people who don’t have the background or the time tend to read a book like that and say, “Oh, look it’s got 500 references in the back, it must be true.” I wanted to write something well-referenced and make a counter-argument. I think there are a lot of problems with his arguments; the energetic aspects of single-cell protein-manufactured foods are quite problematic.

The ecomodernist position emphasizes big-picture, top-down solutions. You’re countering that with what we can do at a much smaller level, fighting against monoculture, advocating for small places, and finding community food solutions. It’s much more challenging to do that on a large scale. Where are people doing this well, and how do we replicate it?

It’s a tricky question. There are loads of people doing it right; the problem is the politics and economics around it that make it so difficult for people to access land and spend time producing food locally.

“We’re overproducing cheap arable grains because it’s so easy to make them extend into landscapes where we probably shouldn’t be farming.”

Plenty of people are figuring out farming that works for them locally in most parts of the world; there’s an Indigenous tradition of land use that we can build on.

Can you talk about agrarian localism?

One of the big debates here in the U.K. is the overproduction of sheep in the upland areas of Britain. That’s partly because the only thing you can produce in upland Britain that you can sell realistically in global markets is sheep, so we’re driven in that way. My argument is that we need the food sovereignty idea developed by Via Campesina: reclaiming food for local communities. Historically, I’ve been a veg grower, and historically, in most places, people would grow their own vegetables, or at least they would be grown locally because it was uneconomic to trot them around. Now, in rich countries, energy is cheap and labor is [expensive], so we import vegetables.

One part of the agrarian localism idea is that if we are moving towards a future of energy constraint, climate change, geopolitical disruption, and, to some extent, the global food system is causing many of those problems, we need to re-localize. Another part of my argument is ecological feedback. If you buy food commodities that come from God knows where, you don’t know the ecological or the social conditions of production, whereas if you’re producing them yourself, or they’re being produced within your community, you are getting ecological and social feedback about the conditions of their production. This is critical for reinhabiting our lived spaces ecologically, making our livelihoods, and knowing the consequences of making a livelihood.

By creating more sustainable and resilient systems that are meaningful to us locally, we can see what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. It’s also self-limiting; once you’ve produced enough food to eat, you stop. We’re overproducing cheap arable grains because it’s so easy to make them extend into landscapes where we probably shouldn’t be farming. With a more localist perspective, you wouldn’t be doing that.

You mention the idea of using less a few times in your book, which I love. What we’re doing now is just not sustainable. There is no magic bullet where people in the developed world can continue to lead their current lifestyle, while we save the planet and feed everybody.

This thinking is a characteristic of ecomodernism. That high-energy, high-capital magic bullet thinking draws a veil over the underlying politics, economic relationships, and inequalities that I think are problematic.

Could you talk about humans as a keystone species?

We get into this mindset where we see humans as gods. We think if we separate ourselves from nature as much as possible, if we all live in cities and let the wild things do their own thing, then we’ll be fine.

“Keystone species are disproportionately impactful species. Humans are clearly a keystone species.”

That’s not going to work at so many different levels. We have to make ourselves the ecological protagonists of our landscapes, which goes back to local traditional farming, wherein people have figured out those ecological relationships.

Humans are great at inventing symbolic systems that overrun the local ecology. Thinking of ourselves as a keystone species gets quite philosophical around human impact; we seem to be in this mass extinction, which is caused by humans.

It’s possible to go to the other extreme, which is part of the ecomodernist view that it’s wrong for us to impact nature in any way. That’s not realistic; we are all organisms that impact each other. Keystone species are disproportionately impactful species. Humans are clearly a keystone species.

We create mosaic landscapes in the same way herbivore-grazing regimes or fire regimes create a mix of open and pit forest habitats, creating niches for all sorts of organisms. Nowhere does it say that humans shouldn’t be part of this push and pull between different species, but we’re getting something badly wrong. We need to find a niche for ourselves to reimagine our relationship with the more-than-human world. How can we be a good keystone species instead of running around knocking over all the china in the shop?

Absolutely. A lot of problems come from trying to separate us from the world.

It’s good to be aware, build in checks and balances, and find a way within our human way of doing things to connect with local potential.

What role, if any, will cities play in your ideal future?

The degree of urbanization in the world has been driven by cheap, abundant fossil energy. Part of the answer to all these questions is about energy futures. If we carry on using fossil fuels, we’re going to torch the planet.

We will likely have to accustom ourselves to a lower energy situation. If we’re manufacturing things and selling them to each other, maybe urbanization is viable [if we are manufacturing food in cities], but I don’t think it’s a long-term, sustainable solution. We’re looking at deurbanization unless there’s some miraculous ecomodernist energy transition. I’d like to think there’s still a place for towns and cities and a mixed landscape of geographic levels. I’m not massively into big cities because, in terms of consumption, they [draw on a great deal of resources from the developing world]. We need to relocalize urbanism so that towns have a real economic and ecological relationship with the hinterland.

There’s a mythology of everyone going to the city to make their fortune. If you think about the history of people migrating to the U.S. and [benefiting from] generating a much bigger economy, then sure. But we’re now in a situation where that isn’t really what’s happening. Increasingly, we’re talking about people in economically precarious situations, a lot of slum dwelling with people in service industries that are very labor-intensive.

The reality of a lot of urban living now, globally, is not particularly positive. What are the implications if we’re talking about more industrial food production—higher yields and less land? Given that one or two billion people in the world are relying on agriculture for their livelihoods? What’s going to happen to those folks?

What do you want readers to take away from this book, outside of being a response to ecomodernists like Monbiot?

We face numerous interconnected problems that aren’t going to be solved top-down by new technologies. The best bet is to work on them bottom up and locally, while connecting positively with people in wider networks. Ultimately, this is going to involve developing new kinds of ecological culture.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.