As summer kicks off, we’ve got more than two dozen books to share with you.

As summer kicks off, we’ve got more than two dozen books to share with you.

June 20, 2024

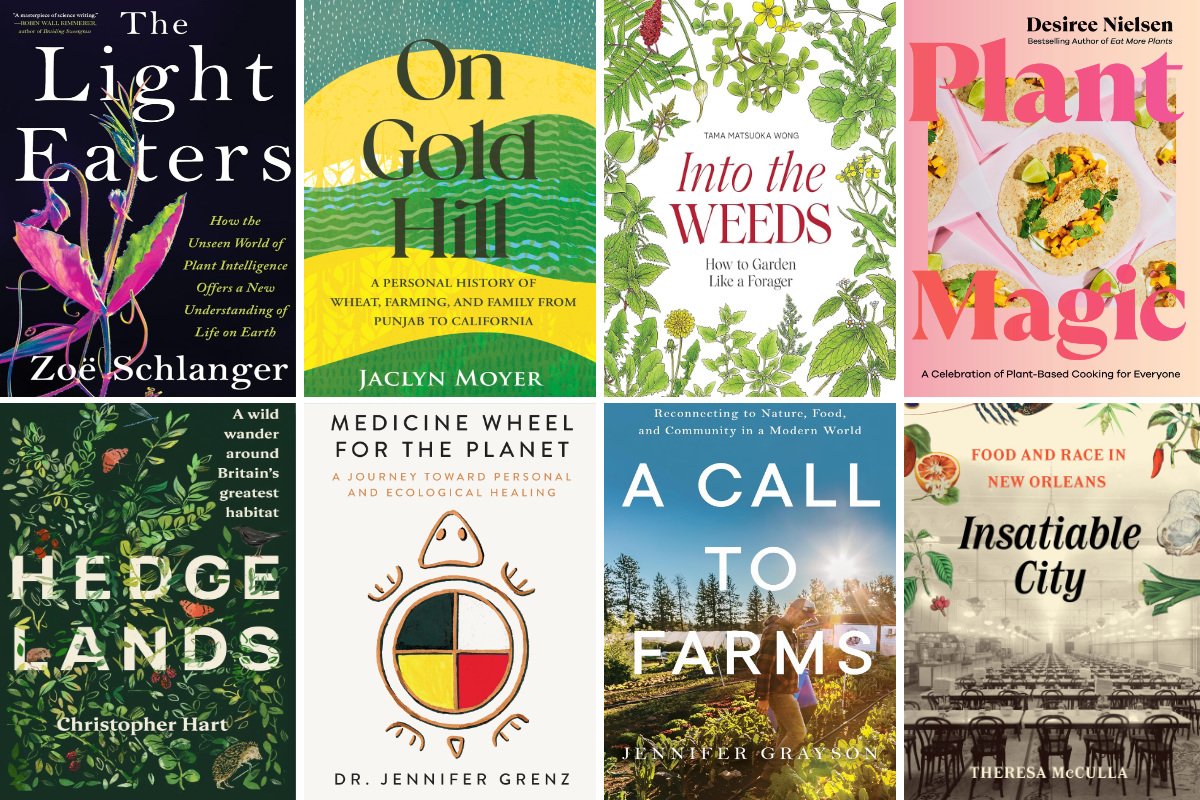

To ring in the first day of summer, we at Civil Eats want to offer you a list of food and farming books we think are worth your time and attention. From memoirs to cultural histories to journalistic inquiries that take on topics ranging from plant intelligence to school food to climate migration, here are 21 titles we hope you’ll enjoy. We even tossed in a few cookbooks to shake up and inspire your summer meal prep. Wishing you time to rest, relax—and read!—in the weeks to come.

If you want to suggest a book we missed, please let us know in the comments below or by email.

Appetite for Change: Soulful Recipes from a North Minneapolis Kitchen

By Appetite for Change, Inc. with Beth Dooley

The dishes throughout Appetite for Change are decidedly Minnesotan. Although items like Cranberry Cream Cheese Bars may have a broad Midwestern appeal, Appetite for Change—the nonprofit behind the book—has a tighter focus. The book’s recipes were developed with a strong connection to the local community. Founded in 2011 as a social enterprise in Minneapolis’ historically Black northside, Appetite for Change uses food, youth programming, and workforce development to build health, wealth, and social change in the community.

The dishes throughout Appetite for Change are decidedly Minnesotan. Although items like Cranberry Cream Cheese Bars may have a broad Midwestern appeal, Appetite for Change—the nonprofit behind the book—has a tighter focus. The book’s recipes were developed with a strong connection to the local community. Founded in 2011 as a social enterprise in Minneapolis’ historically Black northside, Appetite for Change uses food, youth programming, and workforce development to build health, wealth, and social change in the community.

So it’s no surprise that Appetite for Change the book is just as much about community stories as it is food. Take the Purple Rain Salad: An ode to Prince, the recipe—which combines raspberries with cabbage, radish, grapes, and more—was co-created by AFC youth and originally sold at Minnesota Twins baseball games. Eaters of all stripes, from vegans and vegetarians to committed carnivores, will discover recipes they’ll love in this book—and come away with a warm and fuzzy feeling about what’s possible in the world, too.

—Cinnamon Janzer

Transforming School Food Politics around the World

Edited by Jennifer E. Gaddis and Sarah A. Robert

School meal programs are a public good, a form of community care, and a means of advancing broader aims of justice, food sovereignty, education, environmental sustainability, and health. Or so argue university professors Jennifer Gaddis and Sarah Robert, the book’s editors. This collection of 15 essays spotlights how communities around the world are transforming school food programs—and politics—for the better.

School meal programs are a public good, a form of community care, and a means of advancing broader aims of justice, food sovereignty, education, environmental sustainability, and health. Or so argue university professors Jennifer Gaddis and Sarah Robert, the book’s editors. This collection of 15 essays spotlights how communities around the world are transforming school food programs—and politics—for the better.

Written by diverse voices, including youth, teachers, school food practitioners, farmers, and policymakers, the essays offer powerful examples of what could be. Japan’s holistic school meal program, for example, involves children in all aspects of the food cycle, from growing it to washing the dishes, in order to foster community spirit and an appreciation for nature and the food system. Brazil’s national requirement that 30 percent of school food ingredients be sourced from local and regional family farms helps empower and fund women agroecological producers. Meanwhile, in the U.S., Rebel Ventures puts youth at the center of innovating nutritious, enjoyable meals for Philadelphia students, while the Yum Yum Bus, the brainchild of school nutrition workers, ensures that all children who need summer meals get them in rural North Carolina.

Gaddis, an advisory board member of the National Farm to School Network, and Robert, author of School Food Politics, believe that feminist politics, which value the caring labor that goes into feeding and educating children, is essential for transforming meal programs. Additionally, they say, children must have a voice in policymaking. The book is a hopeful, informative read for anyone who seeks to change school food systems.

—Meg Wilcox

You Can’t Market Manure at Lunchtime: And Other Lessons from the Food Industry for Creating a More Sustainable Company

By Maisie Ganzler

Many, many years ago, I spent a long time covering the world of sustainable business practices. It left me with a greater understanding of the complexities of trying to make capitalism less extractive—and it also left me quite cynical about the endeavor. So I was interested to read Ganzler’s how-to book about making, achieving, and maintaining food-industry corporate sustainability goals.

Many, many years ago, I spent a long time covering the world of sustainable business practices. It left me with a greater understanding of the complexities of trying to make capitalism less extractive—and it also left me quite cynical about the endeavor. So I was interested to read Ganzler’s how-to book about making, achieving, and maintaining food-industry corporate sustainability goals.

Ganzler, who leads the sustainability efforts of Bon Appétit Management Company (BAMCO), knows what she’s talking about: BAMCO is recognized as a leader in sustainable food service, especially in the areas of climate-consciousness, local food, animal welfare, and worker rights. In You Can’t Market Manure, Ganzler showcases the commitments of high-profile companies like Stonyfield, Whole Foods, Clif Bar, and others, walking readers through how to best pursue corporate sustainability, set meaningful goals (and adjust when you fail), collaborate with partners and adversaries alike, and sell their company’s story.

While Marketing Manure is surely useful for sustainability leaders—and I also would have found it a priceless tool 15 years ago, when sustainability concepts and practices were fledgling—it also underscores the shortcomings of market-led sustainability. An early chapter focuses on improving chicken farming, touting the success of ambitious projects like No Antibiotics Ever and the corporate Better Chicken Commitment. At the time Ganzler wrote the book, these projects were still on a path to success, but, as we reported last month, have since taken a turn for the worse. Despite all the promises, corporate sustainability commitments will only become reality through consistent pressure and vigilance, and they all too easily devolve into mere lip service.

—Matthew Wheeland

Countering Dispossession, Reclaiming Land: A Social Movement Ethnography

By David Gilbert

Along the slopes of a volcano in Indonesia, a group of Minangkabau Indigenous agricultural workers began quietly reclaiming their land in 1993, growing cinnamon trees, chilies, eggplants, and other foods on the edges of plantations. This marked the beginning of an agrarian movement chronicled by David Gilbert in Countering Dispossession, Reclaiming Land.

Along the slopes of a volcano in Indonesia, a group of Minangkabau Indigenous agricultural workers began quietly reclaiming their land in 1993, growing cinnamon trees, chilies, eggplants, and other foods on the edges of plantations. This marked the beginning of an agrarian movement chronicled by David Gilbert in Countering Dispossession, Reclaiming Land.

An environmental anthropologist and scholar of social movements, Gilbert meticulously traces the two-decades-long effort to reclaim land that had been violently wrested from the local community by Indonesia’s New Order regime. Now the land is marked by a gate that reads “Tanah Ulayat” (Collective Land), leading into a vibrant, shared food forest where small vegetable plots are sheltered by a canopy of trees.

Based on 14 months of ethnographic fieldwork, this book offers a vivid, intimate microhistory of the village of Casiavera, where once-landless workers and peasant farmers created “a new political agroecology.” This scholarship is a work of trust, even capturing the eco-political movement’s emotional undercurrents. “We no longer trembled with fear. No, we were not afraid anymore,” said one resident of Casiavera, recalling a blockade they formed to take back the plantations.

Countering Dispossession, Reclaiming Land is a profound story of what a “land back” movement can look like in practice, reaffirming the possibility that violently occupied land can be reclaimed, from Palestine to Crimea.

—Grey Moran

A Call to Farms: Reconnecting to Nature, Food, and Community in a Modern World

By Jennifer Grayson

The fragility of our food system became more prominent than ever during the COVID-19 pandemic, when supply chains struggled to stay tethered due to global trade disruptions. Six months into the pandemic, journalist Jennifer Grayson uprooted herself and her family from their home in Los Angeles and moved to Bend, Oregon, where Grayson embarked on a regenerative agriculture internship.

The fragility of our food system became more prominent than ever during the COVID-19 pandemic, when supply chains struggled to stay tethered due to global trade disruptions. Six months into the pandemic, journalist Jennifer Grayson uprooted herself and her family from their home in Los Angeles and moved to Bend, Oregon, where Grayson embarked on a regenerative agriculture internship.

In A Call to Farms, Grayson highlights profiles of young farmers—from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Western North Carolina to central Massachusetts—working to create more sustainable farms. Underlying each profile are the effects and unique challenges farmers are facing due to a rapidly changing climate. These snapshots provide a window into a world of farming where young people are actively resisting the industrialized monocultures that dominate our landscape; their farms are often grounded in education, sustainable practices, and, above all, community.

Of her own time in Oregon, Grayson writes, “In my quest to bring my family to live with nature and connect to our food, I had forgotten an essential part of the equation: that throughout human history, neither was possible in the absence of community.”

—Nina Elkadi

Medicine Wheel for the Planet: A Journey Toward Personal and Ecological Healing

By Jennifer Grenz

“To use only fragmented pieces of [Indigenous] knowledge is to admire a tree without its roots,” Nlaka’pamux ecologist turned land healer Jennifer Grenz writes in Medicine Wheel for the Planet. The book details her journey to connect head (Western science) with heart (Indigenous worldview)—the latter of which she says is the “missing puzzle piece” in our efforts to re-establish planetary health amid an ongoing climate crisis. The tome complements her work leading the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Ecology Lab, which aims to restore natural ecosystems and reclaim food systems through community-applied traditional ecological knowledge.

“To use only fragmented pieces of [Indigenous] knowledge is to admire a tree without its roots,” Nlaka’pamux ecologist turned land healer Jennifer Grenz writes in Medicine Wheel for the Planet. The book details her journey to connect head (Western science) with heart (Indigenous worldview)—the latter of which she says is the “missing puzzle piece” in our efforts to re-establish planetary health amid an ongoing climate crisis. The tome complements her work leading the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Ecology Lab, which aims to restore natural ecosystems and reclaim food systems through community-applied traditional ecological knowledge.

A farm kid at heart, Grenz recalls how her perspective was dismissed and disparaged during her 20 years as a Pacific Northwest field researcher, when she was told time and again that she “takes her work too personally.” Instead of becoming discouraged, she doubled down on her unapologetic application of Indigenous wisdom. She encourages all of us to embrace a Native worldview, including the teachings of the medicine wheel’s four directions (as outlined in her book): the North, which draws upon the knowledge and wisdom of elders; the East, where we let go of colonial narratives and see with fresh eyes; the South, where we apply new-old worldviews to envision a way forward; and the West, where a relational approach to land reconciliation is realized. This, Grenz and other Indigenous thought leaders believe, is the only path forward.

—Kate Nelson

The Good Eater: A Vegan’s Search for the Future of Food

By Nina Guilbeault

Nina Guilbeault admits she isn’t the first person you might expect to write about how veganism entered the mainstream. The Harvard-trained sociologist was born to a modest family in the Soviet Union. “Growing up in the rubble of the collapse, we didn’t have much choice about what to eat,” she writes. But her life changed when her beloved dedushka, or grandfather, was diagnosed with cancer and she started to research the link between diet and disease.

Nina Guilbeault admits she isn’t the first person you might expect to write about how veganism entered the mainstream. The Harvard-trained sociologist was born to a modest family in the Soviet Union. “Growing up in the rubble of the collapse, we didn’t have much choice about what to eat,” she writes. But her life changed when her beloved dedushka, or grandfather, was diagnosed with cancer and she started to research the link between diet and disease.

Thus began a global journey to research vegan movements. Guilbeault ventured to Silicon Valley to examine veganism’s transformation from a social movement to a market-based model, and inside the U.S. “vegan mafia” to grasp the millions of dollars behind it. Guilbeault’s personal journey ends up being far more nuanced and complex than she ever expected. “A book I thought would be about veganism turned out to be about the much larger quest of discovering what kind of food system I wanted to build, and how,” she writes. In the end, The Good Eater is a worthwhile examination of eating well in a food system designed for the opposite.

—Naomi Starkman

Food in a Just World: Compassionate Eating in a Time of Climate Change

By Tracey Harris and Terry Gibbs

“Is there such a thing as happy meat?” This treatise on food-system reform poses this question and many others about how political and economic forces often beyond our control shape our dietary choices. How, then, can we foster what the authors term “compassionate eating”?

“Is there such a thing as happy meat?” This treatise on food-system reform poses this question and many others about how political and economic forces often beyond our control shape our dietary choices. How, then, can we foster what the authors term “compassionate eating”?

Learning how food is produced is a significant step, but it’s not easy: “Opacity insulates consumers from the worst practices of food production,” the authors write. Industrialized fish, poultry, and meat processing are far removed from consumer consciousness by design—corporations spend millions lobbying lawmakers to resist transparency, and to eschew regulations that hinder maximum profit.

Another step we can take is recognizing the interconnectedness between the land and its inhabitants, and making this the focus of our decision-making. “What has become increasingly obvious to many is that all struggles for justice for human and nonhuman animals and for environmental harmony are inextricably linked,” the authors write.

Food in a Just World makes this abundantly clear, and points to a largely plant-based diet as a solution for many of our planetary ills. But without significant changes to how we govern ourselves and conduct our economies, this solution seems out of reach. This book reminds us to raise our voices and make individual choices to, as the authors say, “begin to heal ourselves and the planet and everyone on it.”

—Leorah Gavidor

Hedgelands: A Wild Wander around Britain’s Greatest Habitat [U.S. Edition]

By Christopher Hart

Hedgelands is a delightful paean to a staple of British life and a critical part of the nation’s rural ecology: the hedge. Christopher Hart takes readers through the history of the hedge, or hedgerows, as an ancient cultural artifact through to its modern role as a threatened and an unexpectedly diverse and complicated ecological wonderland. Hedgelands reflects deep curiosity about and love for a ubiquitous landscape feature. Hart speaks particularly to “conservation hedges” designed for biodiversity and located along active agricultural lands, estates, woodlands, marshes, and anywhere else human stewardship might imagine.

Hedgelands is a delightful paean to a staple of British life and a critical part of the nation’s rural ecology: the hedge. Christopher Hart takes readers through the history of the hedge, or hedgerows, as an ancient cultural artifact through to its modern role as a threatened and an unexpectedly diverse and complicated ecological wonderland. Hedgelands reflects deep curiosity about and love for a ubiquitous landscape feature. Hart speaks particularly to “conservation hedges” designed for biodiversity and located along active agricultural lands, estates, woodlands, marshes, and anywhere else human stewardship might imagine.

Conservation hedges are growing in popularity worldwide, and this text makes a passionate case for them. Britons have been using a variety of techniques to shape hedges for centuries, and some well-maintained specimens are hundreds of years old. Within a healthy hedge environment, a criss-cross of branches shelters a variety of plants, insects, mammals, and birds that live in harmony with surrounding fields: an estimated 25 percent of Britain’s mammals, for example, call hedges home. The hedge is a unique combination of built and natural environment that reflects complex co-evolution, shaping both British farming practices and the natural environment.

Hedgelands makes an urgent case for conserving the nation’s remaining hedges—only around 400,000 kilometers of hedging remain, with Hart noting that many are in poor condition, consisting of little more than “stumps”—and the loss of this quintessential British symbol could have a profound ripple effect.

—s.e. smith

The Eighth Moon: A Memoir of Belonging and Rebellion

By Jennifer Kabat

The Eighth Moon is a personal history of a place. Set in the Western Catskills in upstate New York, where Kabat moves from London seeking to repair her health, this researched memoir is written in the continuous present, bringing geologic events and Indigenous and white settlements into close perspective.

The Eighth Moon is a personal history of a place. Set in the Western Catskills in upstate New York, where Kabat moves from London seeking to repair her health, this researched memoir is written in the continuous present, bringing geologic events and Indigenous and white settlements into close perspective.

The book opens during the Anti-Rent wars of the 1840s, with a violent populist uprising against unpayable rents, wherein young white men—tenant farmers—donned leather masks, calico dresses, and pantaloons to hide themselves as they rebelled against their landlords, the Dutch heirs who were part of the lingering feudal rent system installed two centuries earlier.

Kabat links this to other rent strikes over the next two centuries, and to the raging populism that began to percolate in the recession of the late aughts in the 21st century. Throughout, she questions hierarchies of ownership amidst people, plants, and the land, while tracing the communal dreams of utopias and cooperative movements that happened nearby. Her parents worked for and were deeply invested in cooperative business structures, from farms to groceries and electric co-ops. In a way, they set the stage for their daughter’s interrogation of how the socioeconomic structures we choose threaten democracy.

—Amy Halloran

On the Move: The Overheating Earth and the Uprooting of America

By Abrahm Lustgarten

On the Move provides a poignant exploration of the climate-driven migration reshaping the American landscape. With scientific rigor and a compelling narrative, Lustgarten vividly portrays communities grappling with escalating climate impacts. As he looks at wildfire-ravaged California,hurricane-battered Gulf Coast towns, and other stricken areas, he critiques the shortsighted policies exacerbating vulnerability, particularly for marginalized communities.

On the Move provides a poignant exploration of the climate-driven migration reshaping the American landscape. With scientific rigor and a compelling narrative, Lustgarten vividly portrays communities grappling with escalating climate impacts. As he looks at wildfire-ravaged California,hurricane-battered Gulf Coast towns, and other stricken areas, he critiques the shortsighted policies exacerbating vulnerability, particularly for marginalized communities.

The book’s emotional core lies in its portrayal of the human toll, from Central American farmers forced to abandon lands due to droughts to other once-thriving agricultural communities enduring ongoing depopulation. Lustgarten forecasts a significant northward shift in America’s climate niche and demands proactive social and infrastructural investments for agriculture and food system resilience.

On the Move offers a blueprint for how we can address climate migration, urging comprehensive strategies that integrate environmental defense and social supports. In doing so, the book compels us to confront one of our era’s defining challenges.

—Jonnah Perkins

The Basics of Regenerative Agriculture: Chemical-Free, Nature-Friendly and Community-Focused Food

By Ross Mars

Of all the buzzwords in the agricultural world, “regenerative” is surely among the buzziest. The label bears a certain aura of righteousness as a step beyond “organic,” yet it’s maddeningly difficult to pin down.

Of all the buzzwords in the agricultural world, “regenerative” is surely among the buzziest. The label bears a certain aura of righteousness as a step beyond “organic,” yet it’s maddeningly difficult to pin down.

The late Australian permaculturist Ross Mars dedicated his career to fleshing out the word in theory and practice. His final work, The Basics of Regenerative Agriculture, offers an accessible primer to a lifetime of learning. Mars argues that any meaningful definition of “regenerative” must concentrate on outcomes, such as increased biodiversity and stable livelihood for farmers, and he shares a list of 20 principles like “enable nutrient cycling” and “enhance ecological succession” as lodestars for the movement. He’s particularly concerned with soil health—“We are technically made of topsoil,” he points out—and readers come away with a deep understanding of how carbon and nutrients flow (aided by charming hand-drawn illustrations).

But Mars believes that a regenerative paradigm shift can heal much more than the soil, transforming all parts of an industrial agricultural system that both contributes to and risks disruption from the climate crisis.

—Daniel Walton

Insatiable City: Food and Race In New Orleans

By Theresa McCulla

Do you know what and who is considered Creole? Insatiable City: Food and Race in New Orleans answers this question and unveils the realities of how New Orleans was founded and who shaped it—both willingly and forcibly. Mixed with doses of food culture, the book delves into the journeys that brought people and food to the city, the lifestyles of free and enslaved Black American laborers along with white powerholders, and tourism.

Do you know what and who is considered Creole? Insatiable City: Food and Race in New Orleans answers this question and unveils the realities of how New Orleans was founded and who shaped it—both willingly and forcibly. Mixed with doses of food culture, the book delves into the journeys that brought people and food to the city, the lifestyles of free and enslaved Black American laborers along with white powerholders, and tourism.

Each chapter captures a different historical aspect of New Orleans’ food and people. One chapter describes the slave trade blocks that were an attraction for tourists, and another juxtaposes luxurious hotels and food with the atrocious cruelties behind the scenes—laborers eating scraps, or no food at all. “Field and Levee” focuses on the huge sugar industry that dominated New Orleans’ economy and the laborers who worked hard on the boats. And “Mother Market” introduces the Choctaw, who established a public market that became a place for Black Americans to trade and sell goods until they were barred, and the market became a place for travelers and the elite to shop. To top it off, McCulla masterfully ties images to newspaper excerpts and individual stories, dipping you into an earlier time in New Orleans.

—Kalisha Bass

On Gold Hill: A Personal History of Wheat, Farming, and Family, from Punjab to California

By Jaclyn Moyer

The child of a forbidden marriage between a white American man and a Punjabi-American woman, Jaclyn Moyer did not learn much about her Indian heritage growing up. Because of the family fracture, she never visited India, did not speak the language, and could not replicate her grandmother’s traditional cooking. That changed, however, after Moyer and her partner established an organic farm on 10 acres in the Sierra foothills of California.

The child of a forbidden marriage between a white American man and a Punjabi-American woman, Jaclyn Moyer did not learn much about her Indian heritage growing up. Because of the family fracture, she never visited India, did not speak the language, and could not replicate her grandmother’s traditional cooking. That changed, however, after Moyer and her partner established an organic farm on 10 acres in the Sierra foothills of California.

The couple decided to grow, in addition to vegetables, an heirloom variety of wheat called Sonora. Moyer soon learned that this variety of wheat originated in Punjab, the region in northern India where her mother was born. “Might this obscure wheat contain within it a door to my own heritage?” she asks. “Could cultivating it offer me an opportunity to make up for all that had not passed down to me?”

In On Gold Hill, Moyer weaves together her attempt to grow the grain with the story she unearths of her family through the generations. She layers these personal narratives with the larger histories of wheat cultivation over the millennia and the more recent organic farming movement. Moyer writes with beautiful, evocative prose. She does not romanticize her own farming experience, or the global chain of events at the center of today’s food and farming systems. This well-researched memoir about identity, heritage, and the systems that feed us is sweet, insightful, and challenging from the first page—and very much worth a read.

—Christina Cooke

Plant Magic: A Celebration of Plant-Based Cooking for Everyone

By Desiree Nielsen

Dietitian and author Desiree Nielsen doesn’t want to tell you what you shouldn’t eat. Instead, she practices “positive nutrition” by advocating for “unrestricted eating” of all kinds of cool plants that should be making their way onto our plates. As she writes in Plant Magic, this approach works because our brains will fight back against restrictions—and because what we put into our bodies will have a greater impact on our health than what we don’t.

Dietitian and author Desiree Nielsen doesn’t want to tell you what you shouldn’t eat. Instead, she practices “positive nutrition” by advocating for “unrestricted eating” of all kinds of cool plants that should be making their way onto our plates. As she writes in Plant Magic, this approach works because our brains will fight back against restrictions—and because what we put into our bodies will have a greater impact on our health than what we don’t.

Nielsen shares her joy for getting more nutrient-dense plants into our diets, with some helpful insights. Chew on a few fennel seeds after dinner to ease digestion and freshen your breath, for example, or incorporate cumin for its anti-inflammatory and digestion-soothing properties. She leans hard into tahini, pairing it with tomatoes and dates; transforming it into a ranch dressing to coat a broccoli salad; or whipping it with sweet potato and harissa for a spicy dip.

If you’re new to plant-based cooking, you may need to add some new ingredients to your pantry, such as spelt flour or hemp hearts. But doing so will open up a new world of meat-free possibilities, and Nielsen promises they will taste good. “If it’s not delicious,” she writes, “what’s the point?”

—Tilde Herrera

Perennial Ceremony: Lessons and Gifts from a Dakota Garden

By Teresa Peterson

In a busy world that seems so often to be filled with struggle, despair, and hate, Teresa Peterson shares a tale of love, wisdom, and reciprocity cultivated through the close observation and attentive following of her garden’s seasonality. Delicately weaving together poetry, prose, and recipes for dishes like Wild Rice, Roast, and Hominy for a Crowd and Zucchini Brownies, Peterson offers an easily devoured glimpse into mitakuye owasin—the Dakota way of living and being in deep relationship with our natural relatives: land, plants, and water.

In a busy world that seems so often to be filled with struggle, despair, and hate, Teresa Peterson shares a tale of love, wisdom, and reciprocity cultivated through the close observation and attentive following of her garden’s seasonality. Delicately weaving together poetry, prose, and recipes for dishes like Wild Rice, Roast, and Hominy for a Crowd and Zucchini Brownies, Peterson offers an easily devoured glimpse into mitakuye owasin—the Dakota way of living and being in deep relationship with our natural relatives: land, plants, and water.

Told through sections that follow the seasons, Peterson brings us along for everything from her struggle to reconcile Christianity with Dakota spirituality to tales of her great-great-grandmother’s eventual return to her homelands. We learn, too, of her encounters with outspoken red squirrels and conversations with university students enrolled in a course on sustainability leadership. It’s gardening as an act of love for Mother Earth that ties these seemingly disparate threads together. “The garden has always been a space for me to work through my own everyday problems or to reflect on issues too big for me to solve,” Peterson writes—a balm for the soul residing in an often-troubled world.

—Cinnamon Janzer

The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth

By Zoë Schlanger

Plants create the oxygen we breathe; they feed and shelter us and an infinity of other creatures; and they delight us in innumerable ways—with their beauty, their fragrance, the shade they provide. Obviously, they’re alive—but how alive, exactly? Over the past 20 years, aided by leaps in technology, botanists have uncovered plant behaviors that challenge our very idea of what a plant is.

Plants create the oxygen we breathe; they feed and shelter us and an infinity of other creatures; and they delight us in innumerable ways—with their beauty, their fragrance, the shade they provide. Obviously, they’re alive—but how alive, exactly? Over the past 20 years, aided by leaps in technology, botanists have uncovered plant behaviors that challenge our very idea of what a plant is.

For environmental journalist Zoë Schlanger, this was a story “too good to stay locked in the realms of academia.” She embarked on a years-long journey, interviewing scores of scientists all over the world and describing, in shimmering prose, their findings: Plants can communicate with one another—and even other species—by releasing chemicals into the air, or through a network of underground fungi. Some plants can recognize genetic kin, arranging their roots and leaves to hospitably share light and soil. They can hear sounds. Plants have recent memories that they pass on to their seeds. A few are able to shape-shift, mimicking the forms of other plants around them.

A rigorous thinker and gifted, expansive storyteller, Schlanger gives us the context to understand what we’re learning, interspersing details of plant physiology with sweeping overviews of how life evolved on Earth, the history of the scientific method, and the place of plants in Indigenous cultures. This stunning book upends our take-them-for-granted view of plants and encourages us to really see them—to our profound benefit.

—Margo True

Amrikan: 125 Recipes from the Indian American Diaspora

By Khushbu Shah

This cookbook explores Indian immigrant foodways in America and invites readers to add these methods and ingredients to everyday cooking. Shah is the first person of color to serve as restaurant editor for Food & Wine magazine, and her enthusiasm will send you straight to the kitchen. She starts by dismantling myths about all Indian food being spicy and overly complicated, then addresses assumptions about vegetarianism and briefly discusses caste and its relation to eating, giving reading references for a deeper dive.

This cookbook explores Indian immigrant foodways in America and invites readers to add these methods and ingredients to everyday cooking. Shah is the first person of color to serve as restaurant editor for Food & Wine magazine, and her enthusiasm will send you straight to the kitchen. She starts by dismantling myths about all Indian food being spicy and overly complicated, then addresses assumptions about vegetarianism and briefly discusses caste and its relation to eating, giving reading references for a deeper dive.

Shah shows you how to stock your pantry and get rolling with simple basics, like Cabbage Nu Shaak, a quick stir-fry that her mother, a dentist, made multiple times a week—and that Shah still makes today, paired with Yogurt Rice, a simple stovetop pudding. Paneer and dal are the starring proteins in this mostly vegetarian cookbook that provides excellent meat alternatives—for instance, the Tandoori chicken wing marinade of yogurt and spices works great on cauliflower.

Using this book is fun, and with Shah’s curiosity as your guide, you’ll be looking at noodles and flour tortillas from a whole new perspective. Dive into cheeky pokes at stereotypes with a bingo board that names common objects of the diaspora and note maybe the best blurb ever—a goofy quip from the author’s father urging you to buy this book because his daughter didn’t become a doctor.

—Amy Halloran

Food Margins: Lessons from an Unlikely Grocer

By Cathy Stanton

Bringing in more grocery stores seems like a straightforward solution to serve communities that lack access to food—especially to diverse and fresh locally grown produce. But what seems like an obvious solution comes with deep-rooted problems that require much untangling. Scholar Cathy Stanton explores these complexities in Food Margins, a blend of history, ethnography, and memoir.

Bringing in more grocery stores seems like a straightforward solution to serve communities that lack access to food—especially to diverse and fresh locally grown produce. But what seems like an obvious solution comes with deep-rooted problems that require much untangling. Scholar Cathy Stanton explores these complexities in Food Margins, a blend of history, ethnography, and memoir.

The book spotlights Quabbin Harvest, a food co-op in downtown Orange, Massachusetts, a former mill town that has seen better days. Ever since Quabbin launched in 2015, it has struggled to stay afloat, at one point on the brink of bankruptcy. Stanton’s book focuses on the co-op’s trials and tribulations as it wrestles with supply chain issues and maintaining its membership base. The book is at its best when Stanton writes about her personal involvement in the initiative; she eventually steps in to manage the business, working with the board, volunteers, and consultants. She packs in gripping stories of how she and fellow local-food supporters try to attract shoppers/members to Quabbin –launching a cooked food line, running fundraisers, creating a share-the-shelf program, downsizing freezers—and covering them with chalkboard signs reading, “We are re-imagining the store” when they couldn’t stock them with enough food. There is a touching story of Dean Cycon, the owner of Dean’s Beans, snapping up Quabbin memberships for all his staff and arranging a credit arrangement to help the co-op keep going.

Ultimately, Food Margins leaves the reader gripped with the question of whether Quabbin will survive and with a deep appreciation of what it takes to bring fresh food to the shelf.

—Amy Wu

Feeding a Divided America: Reflections of a Western Rancher in the Era of Climate Change

By Gilles Stockton

In this collection of interconnected essays, Gilles Stockton straddles two worlds: the bucolic grasslands of Montana, where he ranches cattle and sheep, and the polished halls of Congress, where he’s pushed for agricultural reform as a past president of the Montana Cattlemen’s Association. He ably bridges those perspectives here, exploring “the realities of production agriculture within the context of living in rural America.”

In this collection of interconnected essays, Gilles Stockton straddles two worlds: the bucolic grasslands of Montana, where he ranches cattle and sheep, and the polished halls of Congress, where he’s pushed for agricultural reform as a past president of the Montana Cattlemen’s Association. He ably bridges those perspectives here, exploring “the realities of production agriculture within the context of living in rural America.”

At his best, Stockton comes across like a latter-day Wendell Berry with an economics degree, connecting his unshakeable convictions in the value of rural community with detailed analysis of dysfunction in the livestock industry. While some sections can get wonky, Stockton also keeps his writing grounded in references to his real-world experience, like seeing huge tracts of nearby rangeland be bought up by absentee billionaires. “Is it wise for urban America to continue treating the rural parts of this country as a mere colony?” he asks.

Although Stockton admits that there are no easy answers, Feeding a Divided America advocates for diversified farming and rural respect as good places to start repairing a persistent cultural divide.

—Daniel Walton

Frostbite: How Refrigeration Changed Our Food, Our Planet, and Ourselves

By Nicola Twilley

While a cool drink and a good summer read may go hand in hand, Nicola Twilley’s new book, Frostbite, will have you thinking twice about taking that refreshing sip for granted. As the seasoned journalist and co-host of the podcast Gastropod reveals, the fridge that keeps beer frosty and sprigs of mint fresh is just the tip of the iceberg in the cold supply chain. Starting with refrigerated storage on the farm, the artificial cryosphere includes meat processing facilities, distribution centers, trucks and shipping containers, and supermarket display cases—a vast network designed to ensure safe, efficient, and convenient delivery of food into our iceboxes.

While a cool drink and a good summer read may go hand in hand, Nicola Twilley’s new book, Frostbite, will have you thinking twice about taking that refreshing sip for granted. As the seasoned journalist and co-host of the podcast Gastropod reveals, the fridge that keeps beer frosty and sprigs of mint fresh is just the tip of the iceberg in the cold supply chain. Starting with refrigerated storage on the farm, the artificial cryosphere includes meat processing facilities, distribution centers, trucks and shipping containers, and supermarket display cases—a vast network designed to ensure safe, efficient, and convenient delivery of food into our iceboxes.

Through meticulous reporting—the result of a titanic, 17-year odyssey into the chilly depths of the refrigeration infrastructure, including a stint in the numbing cold of a freezer warehouse—Twilley unveils the history of cold storage and its evolution into the extensive and pervasive refrigerated food system we have today. But despite the technology’s promise to deliver food security and abundance, our seemingly insatiable appetite for manufactured cold comes at a shiver-inducing price, she discovers, with profound impacts on our health, socioeconomic and geopolitical landscape, and climate change.

—Naoki Nitta

The SalviSoul Cookbook: Salvadoran Recipes and the Women Who Preserve Them

By Karla T. Vasquez

As journalists, we understand the importance of documentation—the need to record moments in time to memorialize them in history. As food journalists, we understand even further that how people nurture themselves not only informs their personal identities, but culture as a whole. The SalviSoul Cookbook fully encapsulates food’s power to preserve all of this.

As journalists, we understand the importance of documentation—the need to record moments in time to memorialize them in history. As food journalists, we understand even further that how people nurture themselves not only informs their personal identities, but culture as a whole. The SalviSoul Cookbook fully encapsulates food’s power to preserve all of this.

When author, food historian, and Salvadoran Karla Vasquez started researching Salvadoran cuisine 10 years ago at the Los Angeles Central Library, a librarian tried to help her find recordings of Salvadoran foodways. Coming up short, she quipped to Vasquez that if she wanted to find a book about Salvadoran cuisine, “You’re going to have to write it yourself.” And that’s exactly what Vasquez did.

In addition to recipes, the book contains 33 stories from Salvadoreñas that Vasquez sat down with to speak about their histories. The book makes readers feel like they’re learning to prepare traditional Salvadoran meals with love, while sitting at a table with phenomenal women who crossed borders carrying with them the recipes they used to feed their families. Known as the first exclusively Salvadoran cookbook from a major publisher in the United States, this cookbook creates space for more books that document overlooked foodways.

—Marisa Martinez

Into the Weeds: How to Garden Like a Forager

By Tama Matsuoka Wong

In the popular understanding, hunter-gatherer societies were replaced by those that adopted modern agricultural practices. In Into the Weeds, however, Tama Matsuoka Wong introduces readers to the anthropological concept of the “middle ground” between foraging and farming.

In the popular understanding, hunter-gatherer societies were replaced by those that adopted modern agricultural practices. In Into the Weeds, however, Tama Matsuoka Wong introduces readers to the anthropological concept of the “middle ground” between foraging and farming.

Many people around the world, she explains, have long both collected and tended to plants, and we can follow that example to create “wild gardens of the middle ground.” Into the Weeds unpacks this philosophy and acts as a guidebook for applying it to any backyard. Instead of clearing expanses of arable land, she says, we can plant gardens that build on the existing natural elements of a place, forage for wood sorrel on the edges of garden beds, and gather purslane that’s poking through cracks in cement.

Given Matsuoka Wong’s credentials as forager to renowned New York City restaurants, including Daniel and Atomix, one might imagine her approach to be entirely aspirational. While that’s partly true, the book is also filled with practical advice, like simple instructions for collecting and storing seeds and how to use chicken wire to protect crops from deer. Plus, the entire premise should help relieve the pressure traditional gardeners often feel to create neat, weed-free rows and maintain clearly delineated divisions between what we grow and what grows around us. “In the end, she writes, “nature slips through the boundaries and blurs them.” And that’s a good thing.

—Lisa Held

Other Notable Books

Planting With Purpose: How Farmers Create a Resilient Food Landscape

By Stephen Ellingson

Hungry Beautiful Animals: The Joyful Case for Going Vegan

By Matthew C. Halteman

A-Gong’s Table: Vegan Recipes from a Taiwanese Home

By George Lee

Farmer Eva’s Green Garden Life (a children’s book)

By Jacqueline Biggs Martin

Our Recent Books Coverage

Forage. Gather. Feast. 100+ Recipes from West Coast Forests, Shores, & Urban Spaces

Forage. Gather. Feast. 100+ Recipes from West Coast Forests, Shores, & Urban Spaces

By Maria Finn

One of this foraging cookbook’s goals is to inspire people to develop deeper relationships with their local ecosystems so they’ll be motivated to protect those places.

Devoured: The Extraordinary Story of Kudzu, the Vine That Ate the South

By Ayurella Horn-Muller

Journalist Horn-Muller detangles the South’s fickle relationship with the boundless kudzu vine, chronicling the way it has evolved over centuries and dissecting what climate change could mean for its future across the United States.

Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry

By Austin Frerick

In his new book, the Iowa native and competition expert exposes the system that has allowed seven families, including those behind Cargill, JBS, Driscoll’s, and Walmart, to build enormous power.

The Winter Market Gardener: A Successful Grower’s Handbook for Year-Round Harvests

By Jean-Martin Fortier and Catherine Sylvestre

In his latest book, the Canadian market farmer and educator hopes to inspire a new generation of small-scale farmers to extend their growing seasons in an effort to boost food sovereignty.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.