The author’s new book unveils the transformative impact that manufactured chill has had on our food system—and the frosty consequences of cold-chain dependence.

The author’s new book unveils the transformative impact that manufactured chill has had on our food system—and the frosty consequences of cold-chain dependence.

June 24, 2024

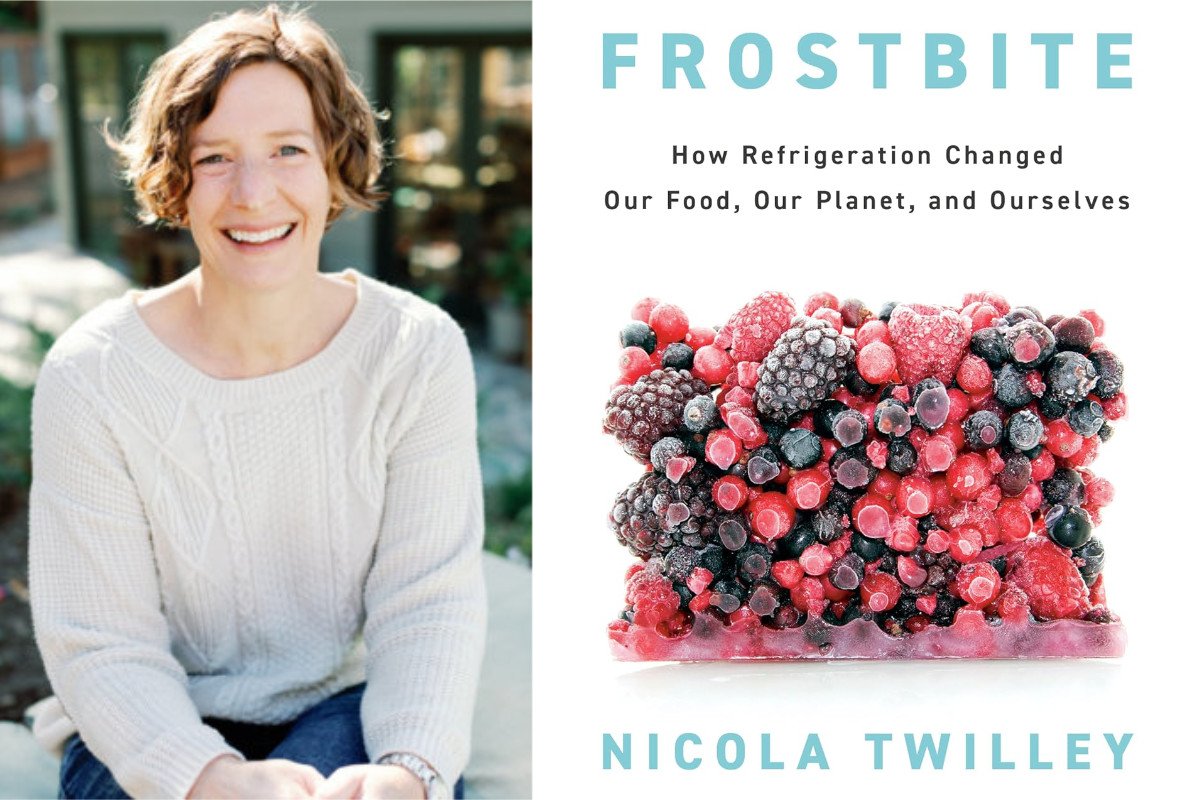

Author photo credit: Rebecca Fishman

A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

In 2012, the Royal Society—the British equivalent of the National Academy of Science—declared refrigeration “the most important invention in the history of food and drink.”

Polemic proclamations aside, refrigeration speaks volumes about our food system, says Nicola Twilley, seasoned journalist and co-host of the podcast Gastropod. The ability to manufacture cold has shaped not just our diet and health, she argues, but our economy, landscape, and geopolitics. “Its fingerprints are everywhere,from the height [increases in] 19th-century army recruits to Irish Independence and women’s liberation.”

“Refrigeration has been seen as an unarguable benefit to society—without it, a third of everything [grown] used to go bad before it could be sold.”

Her new book, Frostbite, plunges readers into the chilly depths of the cold chain—the refrigerated infrastructure that envelops our food as it moves from farm to table—and the far-reaching consequences of developing a food system utterly dependent on cold preservation, storage, and delivery.

As the cold chain continues to expand at a frenzied pace, however, it comes at a shiver-inducing cost, Twilley says—to our health, the socioeconomic and geopolitical landscape, and climate change.

Civil Eats spoke with Twilley about her book, how refrigeration has transformed our relationship with food, and the implications of feeding the world’s seemingly insatiable appetite for manufactured cold.

What exactly is the cold supply chain?

It’s an interconnected network of refrigerated spaces, trucks, shipping containers, and air transportation. About three-quarters of everything on American plates passes through it, starting on the farm, extending to the supermarket, and ending at your fridge. The cold chain has created this vast artificial winter and the global food system that we have today—a world with out-of-season produce, [imported] meats, and Alaskan salmon that’s pin-boned in China, then sold in the U.S.

Can you explain the logistics of creating a cheeseburger entirely from scratch, and how the refrigerated food system makes that possible?

I tell the story of [open-data activist] Waldo Jaquith, who went off the grid with his wife in 2010 to test the limits of self-sufficiency. They built a home in rural Virginia, growing their own vegetables and raising chickens, and set off on a mission to make a cheeseburger—this sort of pinnacle of industrial food—from scratch.

He outlined the steps: He’d grow his own tomatoes, mustard plant, and wheat for the buns. It was the meat and cheese, though, where things fell down. In a pre-refrigeration scenario, you’d slaughter the cow in the cool winter months, but to make cheese at the same time as the beef, you’d need another [cow] that’s nursing [to get the milk and rennet].

Then if you want a tomato on your burger, that’s a late summer produce; if you want lettuce leaf, that’s spring or fall. Without refrigeration, none of those things can be ready at the same time. Sure, you could turn the tomatoes into ketchup and age the cheese. But when you think about how many cheeseburgers Americans eat, bringing those ingredients together in a pre-refrigeration world would have been like dining on a peacock stuffed into a swan—an incredible feat of food sourcing that requires a lot of preparation and planning.

So, the cheeseburger couldn’t have existed without our refrigerated supply chain, and they didn’t; the earliest records are from the 1920s.

Like so many innovations that we consider essential, including the internet, refrigeration comes at a steep price.

It’s a fascinating conundrum. Refrigeration has been seen as an unarguable benefit to society—without it, a third of everything [grown] used to go bad before it could be sold. Food waste has huge environmental and economic impacts on food security, water use, and methane emissions from rotting food, so on that level alone, it’s incredible.

“As consumers, we’ve voted with our dollars to have [produce that’s] cold and sturdy—rather than tasty or healthy.”

Refrigeration allows apple farmers in Washington, for example, to store their annual harvest and spread out sales over the next year. Cold transport allows banana growers in Central America to access a huge export market. People now talk about eating seasonally without having any idea of how it used to be. Historians think that much of Europe used to be pre-scorbutic (a pre-scurvy condition due to vitamin C deficiency) right before spring, from the lack of fresh fruit and vegetables. So, manufactured cold has given us the abundance that we have today, including sheer cool delights like cocktails and ice cream.

Still, a century of refrigeration has also revealed equally enormous downsides. For growers, the economic benefits aren’t so long term: Once the market opens up globally, the money and opportunities tend to go to whoever can do it for the absolute least, and that pushes prices and revenue down for everyone. Refrigeration has contributed to unsustainable monocultures that promote pests, diseases, and resource depletion; although we can have asparagus out of season in the U.S., exports from Peru are draining that country’s aquifer.

The global domination of bananas—the world’s most popular fruit—is made entirely possible by refrigerated shipping and [artificial] ripening. But through consolidation and dependence on a single crop, big plantations in Central America and the foreign corporations that run them have also [left a legacy of] political monoculture in the region.

There are also subtle downsides to taste and nutrition. Fruits and vegetables have been reshaped to fit into a refrigerated supply chain, and part of that has removed flavor—literally switched off genes responsible for producing it. There’s also evidence that nutrient levels have fallen as crops are bred for the cold chain. Yet as consumers, we’ve voted with our dollars to have [produce that’s] cold and sturdy—rather than tasty or healthy.

“The cold chain only makes economic sense at a certain scale, one that tends to rule out small producers.”

At the planetary level, refrigerant gases and the energy used for cooling are among the biggest contributors to climate change. Astonishingly, refrigeration hasn’t reduced food waste—it’s just moved it to the other end [of the consumption pipeline]. In overstuffing our fridges and supermarket shelves, we’re chucking a third of our food supply and [creating even more] greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, the global cold chain keeps expanding—between 2018 and 2020, world [refrigeration] capacity increased nearly 20 percent. I think it’s a potential time bomb.

What is refrigeration’s role in transforming the beef industry?

A lot of the beef industry’s development was driven by the need to feed an increasing urban population. Historically, cattle would walk themselves to market—losing weight en route—and get slaughtered in the city. The cold chain allowed livestock to be raised far away from cities and put meatpacking plants in places where you could bypass pesky things like a unionized workforce. It took skilled butchering jobs away from urban stockyards and made [slaughterhouses] more dangerous.

In the big picture, I think refrigeration contributes to the detachment we have from our meat supply and what happens to these animals before they arrive on our plates. That fosters an approach that says, “I just want the cheapest price possible,” because essentially, that’s the only information we have about the meat.

It’s also led to massive industry consolidation, with four companies now controlling more than 70 percent of the U.S. beef market.

The cold chain only makes economic sense at a certain scale, one that tends to rule out small producers. Cattle farmers in New England, where land is more expensive, can’t compete with those in the American West, who have economic advantages that come with being big. That spurs consolidation: Along with gigantic industrial feedlots, meat processing plants capable of slaughtering thousands of cattle a day have become the norm.

What are the implications of the rest of the world rushing to build U.S.-style cold systems?

Currently, 70 percent of all food consumed in the U.S. passes through a cold chain, while in China, less than a quarter of meats and 5 percent of fruits and veg are sold under refrigeration. With mechanical cooling already responsible for [a significant portion of] global greenhouse emissions, the implications are you can’t build an American-size [system] around the world using current technology and stay within the 2-degree [Celsius global temperature] threshold of the U.N. Paris Climate Agreement. It’s literally not possible.

Conversely, reimagining and reinventing cold technology offers a lot of hope for building a better food system. Rwanda, for instance, is developing a National Cooling Strategy, the first of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa. Although there’s a minimum size required to make refrigeration work economically, in a country where small-scale farmers make up nearly half the population, the system has to be implemented so that it doesn’t throw people off their land or lead to monoculture.

Meanwhile, how can we make the U.S. system more sustainable? The Biden administration is investing in developing a more resilient meat supply chain, for example, largely by decentralizing the industry. Will initiatives like that help?

It’s obviously harder in the U.S., where we have an entrenched system. But there are so many advantages to making things smaller—the industry will definitely be more resilient if one E. coli contamination doesn’t shut down a tenth of your meat supply. While you need to have some level of aggregation, focusing on infrastructure like community refrigeration hubs can help bring the cost of the cold chain down and make [smaller producers] more competitive with agribusiness.

For perishable products, the mantra in the American food system is “the cold chain, the cold chain, the cold chain.” We refrigerate when we don’t need to. If the U.S. mandated salmonella vaccinations for chickens as the U.K. does, you wouldn’t need to refrigerate eggs. Also, there’s a company producing a permeable, edible coating for [harvested] produce that drastically slows ripening—essentially what cold does, with fewer impacts on flavor. Some European countries regulate supermarket size in order to preserve downtowns while curbing massive weekly shopping trips that encourage food waste.

There are solutions at all points along the chain that don’t require new technology. We’re dealing with an entrenched system, however, so we need regulation and incentives to make it work.

As you state, our country’s dependence on refrigeration is disproportionately high—the average U.S. fridge is 40 percent bigger than a French one, while 1 in 4 American households owns multiple units. What can consumers do to wean themselves off cold food?

Unplug that second refrigerator in your garage and recycle it properly to have the gases captured; you’lll find that it reduces food waste and electric bills simultaneously. And there’d be less wishful thinking if we shopped more frequently, in smaller amounts; we buy to fill the space you have. Go to the farmers’ market and buy what’s in season locally. Produce tastes better [that way], too—it’s not just some myth made up by Alice Waters (laugh).

Do you see any glimmer of hope in all of this?

Post-harvest science and technology is this Cinderella-like sector of research and development. There are people doing great work here, but almost nothing is being spent on it. If you want to enter a field that could transform the world, that’s a place where you’re needed.

There’s one striking aspect to note about our food system: It has only been refrigerated for a little more than a century. If it’s that recent, we can transform it.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.