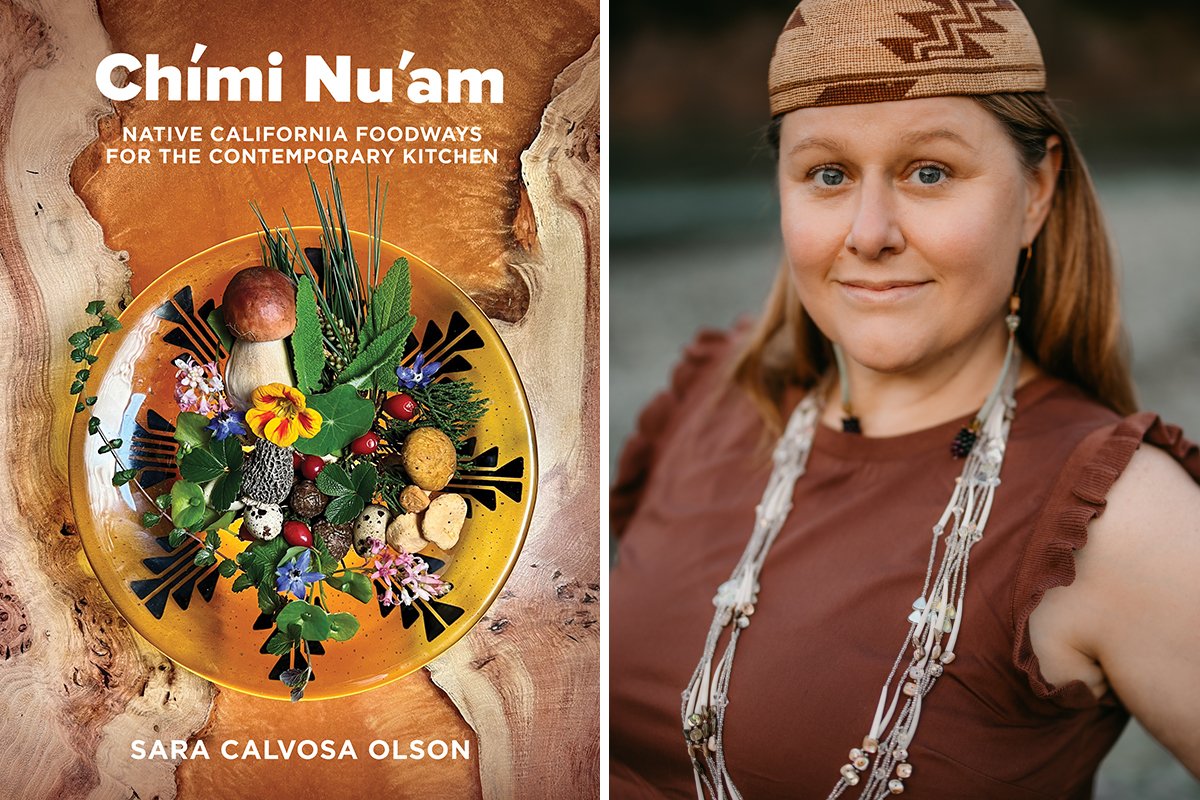

Karuk writer and home cook Sara Calvosa Olson has assembled a collection of Native recipes to help readers reconnect to the natural world.

Karuk writer and home cook Sara Calvosa Olson has assembled a collection of Native recipes to help readers reconnect to the natural world.

November 28, 2023

Photo courtesy of Sara Calvosa Olson

Sara Calvosa Olson didn’t set out to write a traditional cookbook. She had spent several years writing a column about the Indigenous foodways of California for the quarterly magazine News From Native California when she landed a book deal with Heyday Books (the magazine’s publisher) to expand on the column. Then, the pandemic hit and Calvosa Olson turned toward her own kitchen and began writing about and developing recipes based on the meals she’d been cooking for more than two decades. Chími Nu’am: Native California Foodways for the Contemporary Kitchen, released earlier this fall, is the fruit of that labor.

Calvosa Olson grew up with a Karuk mother and an Italian father on a homestead in the Hoopa Valley Reservation, near California’s northern edge. She spent a great deal of time during those formative years outside, learning about her plant and animal relatives and eating a combination of commodity foods and the foods her parents grew, gathered, hunted, and bartered for. “Family celebrations and special foods were formative to the way I now show love and connect to my identity as a flourishing matriarch,” she writes in the introduction to Chími Nu’am.

“We are all colonized, our palates are colonized. And it’s kind of impossible to raise children who don’t love Fruit Snacks and other processed foods.”

Although Calvosa Olson moved to the Bay Area, she stayed in touch with the Karuk community and continued to nurture the food traditions with which she was raised. She writes:

“When I had children of my own, I wanted to connect my sons to these family recipes and to being Karuk, as we were living away from Karuk community and traditional lands. By intentionally establishing this connection, I discovered a love for developing new and colorful recipes based on our old family recipes and traditions. Gathering wild foods, sharing, teaching, cooking, and tending have all been an opportunity to grow and heal in the nurturing way I didn’t know I needed.”

Chími Nu’am, which translates to “Let’s eat!” in the Karuk language, is in many ways a record of that process in addition to a compendium of recipes. Organized by season, the book guides its readers in gathering, processing, and cooking with Indigenous foods in hopes of helping us begin to integrate more traditional ingredients into our oversimplified modern palates.

Its recipes range from creative takes on familiar foods—blackberry-braised smoked salmon and elk chili beans—to dishes that will be entirely new to many readers, such as nettle tortillas, miner’s lettuce salad, and spruce-tip syrup. And it includes recipes for nearly a dozen foods made with acorns, including crackers, muffins, crepes, and hand pies, as well as a rustic acorn bread that calls for one cup of acorn flour and two cups of wheat flour.

Calvosa Olson has written a book that will speak to multiple audiences. But whether she’s guiding Indigenous readers to embrace more of their cultural foods or making recommendations for non-Indigenous readers interested in decolonizing their diets in an ethical way (hint: it’s about reciprocity), her voice and philosophy come through clearly on the page.

Civil Eats spoke to Calvosa Olson recently about the book, how she hopes it will reach those very different audiences, and her urgent call to all of us to begin reconnecting to the natural world through food.

How did the recipes in the book take shape, and how did you decide what to include and what to leave out to protect or preserve specific cultural foods and traditions?

I think we can all agree that Native people have lost so much, and so much has been taken, appropriated, and diluted. There are still some cultural foodways that are very similar to the foodways that we have always eaten. And because there are so few, I didn’t feel like it would be appropriate to put those in a book for everybody. Even in the work that I do for my own family, there’s a difference between what is for us in ceremony and what is for us to incorporate in our everyday lives or to maintain our connection to our stewardship.

We are all colonized, our palates are colonized. And it’s kind of impossible to raise children who don’t love Fruit Snacks and other processed foods. But I really wanted them to develop a love for foods that are bitter or fishy—those types of things that we shy away from in Western culture.

“We are all suffering from diet-related diseases. It’s terrible. And it’s so difficult to right that ship for many reasons.”

Different audiences will experience this book differently, but as a non-Indigenous reader, I felt invited in—invited to take part and understand more of the cultural experience behind these foods rather than merely follow recipes. That said, gathering and preparing these ingredients is also going to be a learning curve for some readers.

We all need to develop relationships with our foodways, and our lifeways, and what’s going on around us. Nobody can turn on the news and disagree with that. We need to at least develop some relationships with the rhythms of the world around us right now. So, I want the book to be a warm welcome in to do that.

But also, how you do that is very important. And I love that people are asking: How do I do it ethically? You have this opportunity to go forward intentionally and choose the lens that you want to view this work through, and you can center Indigenous people, and our traditional knowledge and our relationship-building and community-centered lifeways, as you go forward. Which means that you are also building relationship and building community with Indigenous people and we’re all working together.

And how do you interact with Native people who have been deliberately othered in the state, and deliberately made invisible? Growing up in the U.S., we don’t hear from Indigenous people, and that’s what causes a lot of the mystic Indian tropes. And you can see that in the [U.S.] education system, which ignores Native people, and refers to us in the past. But we are still here, and we are safeguarding so much of the world’s biodiversity.

We’re also at the forefront of environmental science; we have incredibly sophisticated people working in our environmental departments. We have climate action plans, we have stewardship plans, we have everything we could possibly need to go forward to rehabilitate the land except power and influence. Even if I only reach one person at a time, and they went about things in a different way and began to understand the value of [traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous foodways] in a new way, that would be a success.

You recommend that non-Native folks contact their local tribal representatives when they want to learn how to gather acorns and other Indigenous ingredients. What do you say to people who worry that they’d be bothering them in asking for their services?

There are non-Native people out there who run foraging classes and you have the choice to either pay them or you can call or email tribal peoples or tribal entities and say, “Listen, I’m interested in learning more about this. And I can pay non-Native foragers, but I would prefer to put my resources with you. I want to center your knowledge. Do you offer any classes to the public for gathering or know of anybody willing to show us how to gather?”

I realize it’s uncomfortable! Because, again, [people are used to] othering of us, and don’t know how to interact with us. They feel like they’re going to bother us. But that just keeps people going to foragers who are non-Native. But overcoming that awkwardness is important because the worst thing that can happen is that they can say, “Yikes, we don’t know anybody.”

“People are still reliant on commodity food and subsistence gathering. And often when you go out to gather your traditional foods, they’re not there anymore.”

You share strategies for decolonizing your diet gradually by adding, for example, a cup of squash to frybread or a cup of acorn flour to bread to replace processed white flour. Can you say more about that approach?

Because our palates are all colonized, to some degree, we have to reintroduce these foods gradually. There’s a dilution that occurs. But I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad thing. Because we can’t all go rushing into the forest right now to completely decolonize our diets. It’s impossible. We would we need to set up new food systems that are as robust as the ones we have now before we could do that. This is a gradual change.

One cup of acorn flour instead of one cup of white flour is still one less cup of white flour. In [Indigenous] communities that really matters. We are all suffering from diet-related diseases. It’s terrible. And it’s so difficult to right that ship for many reasons. There’s so little food education, no access to healthy foods. People are still reliant on commodity food and subsistence gathering. And often when you go out to gather your traditional foods, they’re not there anymore. The fish are gone and the fires have burned the mycelium mats, so the mushrooms aren’t coming back the same.

Anything that we can do to start turning this ship around is important. And it’s about eating and nourishment, yes. But it’s also about connecting to community and connecting to our role as people for the environment—and waking up to our obligations to everything around us.

You recommend that readers start to expand their worldview and their approach to Indigenous foods slowly, but you also go on to write, “I want to impress upon everybody the urgency with which we must act to keep our ecosystems healthy.” How do you balance that desire to move slowly and build deeper connections to ecosystems against that larger sense of urgency?

“Hurry up! And go slow”—that’s what I’m telling people. Connecting to this approach requires you to go slow in the beginning, but as you develop your own connections and your own relationships it’s like a snowball; it will start to build on itself exponentially. And you will become more attuned to these issues and more connected to the activism that Indigenous people are engaged in. And then, in a year, you will have so much more knowledge and it will be an exponential leap to the next year. And it goes on from there. If you go too fast, and you’re not developing relationships or practicing reciprocity, then you’re just perpetuating the same cycles of settler colonialism and extraction that got us into this mess in the first place.

You worked with the California Indian Museum and Cultural Center teaching cooking to Indigenous elders during the pandemic. Can you speak to how that work helped shape this book?

Indigenous readers were really the first and only audience that I was considering at first. This whole book took a lot of checking in with community and gut-checking constantly about how to go forward and be inclusive, because I really, genuinely believe that we need everybody together to do this. And I don’t think that Indigenous people alone can do this. But I do want to prioritize the health of our communities first, because I want us to be healthy and ready to keep it up.

“We are reclaiming that history and knowledge, and we have to teach it to our children.”

As lost as [non-Native people] might feel sometimes about how to go forward and who to ask about Indigenous foods and practices, we often feel the same way. Many Native people are disconnected from family and community, and they’re spread out or flung all over the place. For instance, I’m on Coast Miwok land, but I’m not Coast Miwok, so I’m still a guest on this land. How do I go forward here in a way that centers reciprocity? And we’re all asking these kinds of questions.

Most of our foodways were not documented in California because it was considered “women’s work.” We just have smoked salmon and acorn soup. I know we had a massive variety of foods, and it was vibrant, colorful, nuanced, and delicious. And yet, if you were to read documentation about the Karuk tribe, you would see that we only ate two things.

We are reclaiming that history and knowledge, and we have to teach it to our children. And sometimes I teach it to older people who were sent to boarding schools or whose parents were sent to boarding schools and didn’t want to have anything to do with their indigeneity when they returned. It is complicated for all of us. There are not very many people doing this work in a way that is engaging all people. And that’s mainly because there are so few of us and the first focus has to be on fortifying the people in our own communities. But I’m a white Indian, so I want to be able to leverage my whiteness to speak to a non-Native community, and to engage them about how to go about this in a good way. I’m like a liaison.

I have a whole half of me that isn’t Native, and it’s a challenge to reconcile these two sides. But I don’t have to reconcile them right now. What I can do is use what was good on [my Italian side]—the things I learned about family and community and how to show my love through food and laughter and storytelling—to uplift the Native people in my communities.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Muffins are such a forgiving bake, so this is a great place to mess around with some dried fruits and toasted nuts if you like a little extra something in your morning nosh. Muffins are also very easy for little hands to make! Get the niblings involved with this one.

Makes 12 muffins

1½ cups all-purpose flour 1⁄2 cup acorn flour

½ cup chocolate chips (see Note)

¼ cup maple sugar

1½ teaspoons baking soda

1½ teaspoons baking powder

1½ teaspoons pumpkin pie spice

½ teaspoon salt

1⅓ cups whole milk

1 large egg

1 tablespoon pure vanilla extract

1 cup cooked squash puree

Note: This is a very forgiving recipe, so you can add more or fewer chocolate chips or substitute them with dried fruit and/or nuts.

Preheat the oven to 375°F.

In a large bowl, mix together the flours, chocolate chips, maple sugar, baking soda, baking powder, pumpkin pie spice, and salt.

In another large bowl, mix together the milk, egg, vanilla, and squash puree.

Stir them together to form a batter. Do not overmix. Fill the cups of two 6-cup muffin tins three-quarters of the way full.

Bake for 20 minutes, until a toothpick inserted into the center of a muffin comes out clean.

This recipe is excerpted from Chími Nu’am: Native California Foodways for the Contemporary Kitchen by Sara Calvosa Olson. Reprinted with permission from Heyday © 2023.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.