Walmart and the Walton Family Foundation have relied on a debatable definition of “sustainable” seafood that allows it to achieve its sourcing goals without fundamentally changing its business model.

Walmart and the Walton Family Foundation have relied on a debatable definition of “sustainable” seafood that allows it to achieve its sourcing goals without fundamentally changing its business model.

November 21, 2023

Photo credit: Scott Carr, Getty Images; illustration by Civil Eats

Portions of this essay were previously published as “Walmart’s Ocean: Certifications, Catch Shares, and the Ripple Effects of Corporate Governance on Marine Environments” in Big Box USA: The Environmental Impact of America’s Biggest Retail Stores. Eds. Bartow Elmore, Rachel Gross, and Sherri Sheu. 2023. Colorado University Press.

In March 2023, consumers filed a class action lawsuit against Walmart. This is not unusual—Walmart gets sued about 20 times per day. What was unusual was the reason: The lawsuit alleged that Walmart misled consumers by selling seafood products “certified sustainable” by the nonprofit Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), advertised with a prominent blue checkmark in the shape of a fish.

The lawsuit alleged that “as Walmart knew or should have known, MSC hands out this certification to those who use industrial fishing methods that injure marine life as well as ocean habitats with destructive fishing methods . . . Reasonable consumers believe the fisheries providing these products are maintaining healthy fish populations and protecting ecosystems.”

In fact, the MSC standards themselves promise such protections for the oceans, marine life, and humans. However, the suit also alleged that MSC-certified fisheries engage in the suffocation and crushing of dolphins caught in fishing nets, the killing of endangered sea turtles caught on hooks, and the entangling of critically endangered whales in fishing gear.

“Walmart failed to ensure that the fisheries only sourced using sustainable means, making its promises meaningless,” the lawsuit claimed.

The litigation is unlikely to result in a massive payout for Walmart shoppers. Walmart has moved to dismiss the lawsuit and has stated that “the MSC URL included on the product packaging . . . informs a reasonable consumer what ‘sustainable’ does and does not mean in this context,” while the MSC—which has responded to similar criticism in the past—has not issued a statement.

As a historian of science researching the history of fisheries science, sustainability, and ecosystem and food system management, I believe that this litigation, and similar critiques, raise questions about the Marine Stewardship Council’s rapid rise to prominence and its unique relationship to the world’s largest retailer.

MSC’s influence extends far beyond Walmart. Perhaps the most prominent sustainability certification label for sustainably caught wild fish, it can be found at restaurant chains from McDonald’s to Red Lobster and Olive Garden, and on canned tuna brands including Bumblebee and Chicken of the Sea. Retailers from Costco and IKEA to Whole Foods increase MSC’s credibility among shoppers.

But it turns out that Walmart’s support has been essential to the development and scaling up of MSC’s certification, and perhaps also key to what critics view as the certification’s weaknesses. To understand the rise of MSC, we need to look back into the history of Walmart.

What began as a single general store, “Walton’s 5-10,” in 1950, has become almost incomprehensibly vast, operating on a scale that is larger than that of many countries. Each week, 265 million people shop at Walmart somewhere in the world. By 2018, Walmart controlled 26 percent of the grocery market in the U.S. (as much as 90 percent in some locations), and was called the largest fish retailer in North America by 2015.

“Walmart’s support has been essential to the development and scaling up of MSC’s certification, and perhaps also key to what critics view as the certification’s weaknesses.”

In 2006, however, Walmart faced two serious problems, one relating to supply and the other to demand. On the supply side, Peter Redmond, Walmart’s vice president for seafood and deli, fretted over insecurity in Walmart’s supply chain as the retailer rapidly expanded into the grocery sector.

“I am already having a hard time getting supply,” he reported. “If we add 250 stores a year, imagine how hard it will be in five years.” Walmart’s business model requires suppliers to be consistent, reliable, transparent, and agreeable to changes, particularly price reductions. A complex seafood supply chain where a single fillet might change hands half a dozen times met none of these criteria.

Redmond was concerned about receiving inferior products—or possibly none at all. Over the prior two decades, several huge, historically stable fisheries, including the famed Newfoundland and Grand Banks cod fishery, had collapsed, and a controversial but widely reported scientific paper warned that all commercially fished stocks could collapse by 2048.

On the demand side, put simply, Walmart had an image problem. Once considered “America’s Most Admired Company,” Walmart had begun receiving a torrent of negative publicity on issues ranging from alleged bullying tactics over a proposed store location to allegedly encouraging employees to rely on Medicaid and food stamps (and in one case, holding a food drive for its own food-insecure employees) to compensate for Walmart’s low wages.

Into this breach stepped Rob Walton, son of founder Sam Walton, whose family remains Walmart’s most influential investors. Rob was growing concerned with both the company’s image and the planet’s environmental trajectory. He arranged for his close friend and diving buddy Peter Seligmann, chairman of environmental nonprofit Conservation International, to meet with Walmart’s then-CEO Lee Scott. Seligmann helped convince Scott that a commitment to sustainability would provide much-needed good publicity, while helping secure the stability of volatile supply chains like seafood.

In August 2006, Walmart announced a multi-faceted campaign to go green. For seafood, the corporation began selling products with the Marine Stewardship Council MSC-certified label. They started with 10 products from Beaver Street Seafood and AquaCuisine but had bigger ambitions: “We have set a goal to procure all wild-caught seafood for North America from fisheries certified by the MSC within the next three to five years,” Redmond announced.

Founded in 1997, MSC allowed fisheries to apply to receive its signature blue checkmark by hiring a third party to assess the fishery according to 23 principles. Those principles included priorities such as helping overfished stocks recover and avoiding overfishing and practices that degraded ocean habitat. The assessment was then opened to public comment and objections, redrafted, and the fishery certified or rejected. Certified fisheries undergo reassessment every five years. The process is similar today.

At the time, MSC publicly rejected the role of governments, centering the roles of consumers, environmental groups, and industry instead. A 1996 paper by MSC founder Michael Sutton featured a prominent epigraph from the Secretary General of the U.N. Environment Program (UNEP) stating simply, “The market is replacing our democratic institutions as the key determinant in our society.”

“Walmart’s partnership with MSC turned certification from a value-added product to a necessity for its seafood suppliers. Those businesses now had to pay for the MSC certification process.”

Despite UNEP’s warning tone, Sutton saw this not as a problem, but as an opportunity; the state had failed to manage fisheries sustainably, so it was time to let market forces work their magic. “Government, laws, and treaties aside,” Sutton wrote, “the market will begin to determine the means of fish production.” This pro-market belief fit well with their future partners at Walmart: the Walton family, who own a controlling share of Walmart and whose eponymous Walton Family Foundation was garnering a reputation in the early 2000s for supporting free market causes, including charter schools and school vouchers.

Walmart wasn’t the first retailer to adopt MSC certifications, but it was the biggest, and where Walmart went, other industry players followed. Walmart’s partnership with MSC turned MSC certification from a value-added product to a necessity for its seafood suppliers. Those businesses now had to pay for the MSC certification process (a cost MSC estimates between $15 to $120,000 in consultant fees), if they wanted to keep selling to Walmart (as well as an additional 0.5 percent in royalty fees to MSC if they want to use the MSC logo).

Within the decade, many other major retailers including Aldi, Carrefour, IKEA, and Tesco, and restaurant chains like McDonald’s and Darden, the owner of Olive Garden and Eddie V’s Prime Seafood, had partnerships with MSC.

MSC also received money from the Walton Family Foundation, run by the children and grandchildren of Sam Walton, including Rob Walton, who helped convince Walmart’s CEO to embark on the conservation program in the first place. In 2010, the foundation was MSC’s largest single donor, contributing $4.5 million. Walton Family Foundation donations to MSC fluctuated over the next decade but often exceeded seven figures, including a 2021 grant of $1.05 million.

“In 2015, 73 percent of the organization’s income, or $14 million, came from charging seafood companies 0.05 percent of the wholesale value of sales to use its label, according to a leaked WWF report.”

In 2010, in the same newsletter announcing their partnership with Walmart, the MSC also announced a “new strategic plan [that] sets out how we will scale up our activities and accelerate the delivery of our mission.” After “an intensive planning process generously funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation,” MSC accelerated development. Their budget increased from a little over $2 million in 2005 to nearly $20 million in 2013, and the number of certified fisheries increased seven-fold from 2006 to 2013.

But scaling rarely comes without turbulence, and an enlarged MSC quickly found itself navigating rougher seas. An increasing number of scientists and conservation groups, from Greenpeace to Pew Environmental Group to MSC’s co-founding organization, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), found fault with MSC practices.

Some were concerned with MSC’s objection process, in which any outside organization concerned about a pending certification—often environmental groups or fishers from adjacent fisheries—paid up to £15,000 to lodge complaints (in August 2010, the maximum fee was lowered to £5,000). Those objections were also handled by lawyers who were explicitly instructed not to consider biological critiques, and objections almost never succeeded.

Others were concerned that MSC had a significant, and increasing, financial interest in certifying fisheries: In 2015, 73 percent of the organization’s income, or $14 million, came from charging seafood companies 0.05 percent of the wholesale value of sales to use its label, according to a leaked WWF report. The MSC thus had direct financial incentive to certify more fisheries and allow larger catches.

“MSC’s definition of sustainable fishing was loose enough to justify the certification of fisheries that were overfished or where overfishing was ongoing. Those words—overfished and overfishing—don’t have a universally agreed-upon definition.”

WWF characterized MSC as having “aggressively pursued global scale growth” and said it had “begun to reap very large sums from the fishing industry.” MSC Science and Standards Director David Agnew denied “any conflict of interest with his organization’s logo licensing or financial model,” while WWF characterized the report as an unofficial working document that was part of an “ongoing dialogue that we are having with the MSC to drive positive change in the marine environment.”

But there was an even deeper critique. MSC’s definition of sustainable fishing was loose enough to justify the certification of fisheries that were overfished or where overfishing was ongoing. Those words—overfished and overfishing—don’t have a universally agreed-upon definition. So, MSC, critics say, set the bar low, using one of the most permissive definitions. Under a more stringent definition, a third of its certified fisheries failed to meet the mark in a scientific review.

And MSC-certified fisheries can also do enormous environmental damage. Even though MSC’s principles clearly state that certified fisheries should not damage ecosystems, the only fishing techniques that are explicitly banned are dynamite, poison fishing, and shark-finning. Other fishing methods that have been attributed to high rates of bycatch and ecosystem damage—including bottom trawling and longlining, the standard practices of well-capitalized, wealthy countries like the U.S.—are not considered inherently unsustainable but run against its principles, although they are still permitted under the certification. For instance, the MSC-certified Northeast Arctic saithe fishery uses bottom-trawling, and therefore catches endangered golden redfish, too.

“Proponents of the MSC argue that it serves as an incentive for those in certified fisheries to avoid overfishing, no matter how large or industrialized, while detractors suggest that it can greenwash unsustainable and damaging fisheries, all while keeping demand high among unsuspecting consumers.”

This is just one way MSC certification has benefited wealthier fishers and their industries. Smaller-scale fishers, often from heavily fishing-dependent communities, are also less able to afford the certification fees and never get certified in the first place. In a marketplace saturated with MSC’s blue checkmark, they lose market leverage, even if they use more environmentally friendly techniques, are more sustainable, and provide greater employment and food security.

Even so, small-scale fishing vessels were alleged to disproportionately feature on MSC’s promotional material in a 2020 study in PLOS, the nonprofit academic journal. MSC disagreed with this analysis, in particular defending the potential sustainability of large industrial fisheries, but also affirmed that as of 2020, “the percentage of small-scale fisheries achieving MSC certification [was] . . . around 16 percent,” while “small-scale fisheries account for roughly 90 percent of fishers.” MSC also called attention to a new initiative, the Ocean Stewardship Fund, which has dedicated over $4.9 million to over 106 diverse fishery improvement projects in small-scale and developing nations fishing programs.

But did MSC actually improve the stocks of the fisheries themselves? Proponents of the MSC argue that it serves as an incentive for those in certified fisheries to avoid overfishing, no matter how large or industrialized, while detractors suggest that it can greenwash unsustainable and damaging fisheries, all while keeping demand high among unsuspecting consumers.

Walmart’s own shifting sustainability goals fed detractors’ concerns: It amended its initial goal of only stocking certified sustainable fish to include fisheries “on their way” to earning a sustainability label. By 2017, Walmart’s official Seafood Policy claimed that by 2025 all seafood would be sourced from fisheries that are “third-party certified” by the MSC (or some other certifier recognized by the Global Sustainable Seafood Initiative), or “actively working toward certification.”

The MSC itself has also issued certifications for fisheries aspiring to, but not yet achieving, sustainability. WWF, no longer affiliated with MSC, raised the alarm, arguing that the certification of fisheries targeting endangered bluefin tuna by Japan and France at the time was premature. Wasn’t the MSC supposed to certify fisheries that were already sustainable, not reward aspirations alone? Now Walmart’s “100 percent sustainable” seafood department could stock products from fisheries “on their way” to receiving a certification that said they were on their way to sustainability.

MSC later claimed that WWF’s concerns had been addressed, arguing, “The assessor’s recommendation for the MSC to certify the fishery is informed by the latest scientific advice,” with contributions from marine scientists and NGOs, including WWF.

“Walmart’s partnership with MSC has helped make the concept of sustainable fish—the concept of sustainability itself—into a commodity, sellable through a blue checkmark.”

Nevertheless, this is how Walmart’s partnership with MSC has helped make the concept of sustainable fish—the concept of sustainability itself—into a commodity, sellable through a blue checkmark. In some cases, MSC certification may have saved thousands of seabirds and other marine life, while in others it may have greenwashed unsustainable fishing practices and hurt other conservation efforts.

It also has a clear effect on the fishing industry, which now must navigate an expensive new market of certification consultancies that favors large industrial fisheries over small community-based ones. MSC has heard this criticism, and has worked toward getting smaller-scale fisheries in poor countries certified. Unknown, however, is whether those fisheries can still support local communities once they are part of an MSC program. The programs are, after all, market tools for global supply chains, and can untether local fisheries from their otherwise protein-sparse communities when the resources of poor countries are used to feed rich ones.

Despite Walmart’s success in shaping the narrative of sustainability, Walmart’s seafood policy demonstrated the limits of stateless corporate governance. Twenty years later, Walmart may be discovering what other observers believed from the start: Markets have not shown themselves singlehandedly capable of enforcing sustainable fishing. Only governments can enforce the compliance that certifications generally call for.

So, while for decades, Walmart, the Walton Family Foundation, and its partner, the MSC, advocated for market-based environmentalism, all have since had to turn to traditional governing bodies to meet their sustainability commitments and call for more action from regulators. In an interview with me in 2021, Teresa Ish, Walton Family Foundation’s oceans initiative lead and senior environment program officer, said, “It is kind of ironic that it all comes back to that management side, but that’s where we are now.”

“For decades, Walmart, the Walton Family Foundation, and its partner, the MSC, advocated for market-based environmentalism, all have since had to turn to traditional governing bodies to meet their sustainability commitments and call for more action from regulators.”

What this means in practice is that MSC and the Walton Family Foundation, both historic advocates for free-market environmentalism and limited regulation, have recently been in the position of “asking” the governments of countries where Walmart buys fish to bolster their fishery management and regulatory efforts.

This can take the form of open letters like the one signed by Walmart, Carrefour, Nestlé, Publix, and Tesco in May 2020 calling on governments to allow electronic monitoring of tuna vessels during the COVID-19 pandemic so that the retailers could still meet their product commitments while the human observers who keep tuna fishing sustainable were off-duty for safety reasons.

Or devising fishery improvement plans (FIPs)—in which certifiers or industry or others call for a rearrangement of fishery management in exchange for funding—which the Walton Family Foundation’s own consultants have found “must compel governments to adopt changes” in order to succeed and often still result in adverse outcomes for local communities.

For its part, MSC has announced, “Governments must cooperate to seize the opportunities of a blue revolution.” This while its Ocean Stewardship Fund is providing research for international fishery management agencies and hoping to influence multinational fishery management regulations—important work, but not easily classifiable as market-based environmentalism.

“It’s just a definition of sustainability compatible with late-stage capitalism, unlikely to be compatible with complex ecosystems, unpredictable population fluctuations, and a changing climate.”

In some ways, we have come full circle, back to traditional environmental strategies like government regulations that use lawsuits to enforce them. And yet Walmart’s corporate governance strategies have allowed it to rely on MSC’s debatable sustainability criteria in such a way that, combined with charitable giving from the Walton Family Foundation and other philanthropic partners, Walmart can achieve its sustainability goals without fundamentally changing its business model.

This reformulated sustainability doesn’t solve the problems associated with producing low-cost disposable goods and shipping them across the world, or relying on the continued, predictable harvest of wild animals with naturally fluctuating population dynamics. It’s just a definition of sustainability compatible with late-stage capitalism, unlikely to be compatible with complex ecosystems, unpredictable population fluctuations, and a changing climate.

This contradiction at the heart of a sustainable Walmart is elided by the company’s rhetoric. By declaring that MSC certification means a fishery is sustainable, Walmart is shifting the burden of proof onto anyone who says their products are not sustainable, or who has a different, perhaps more rigorous, definition of sustainability. Walmart is relying on both certification itself and whatever ecological results it has as positive environmental outcomes—as sustainable. This is an important aspect of corporate greenwashing: moving the goalposts.

Now, this mismatch between reality and rhetoric could get even more problematic: In 2020, Walmart President Doug McMillan announced that Walmart aims to become “a regenerative company—one that works to restore, renew, and replenish in addition to preserving our planet.” But how can a company whose business model depends on moving cheap goods and extracted resources be, on net, ecologically regenerative?

Barring a substantial shift in that business model, which may entail higher prices on consumer goods, it seems more likely that regenerative, like sustainable, will become a word whose meaning is determined by Walmart.

For additional reading on this subject:

Charles Fishman, The Wal-Mart Effect: How the World’s Most Powerful Company Really Works and How It’s Transforming the American Economy (New York: Penguin Press, 2006); Nick Copeland and Christine Labuski, The World of Wal-Mart: Discounting the American Dream, (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013); Anthony Bianco, The Bully of Bentonville: How the High Cost of Wal-Mart’s Everyday Low Prices Is Hurting America (New York: 2006); Carolina Bank Muñoz, Bridget Kenny, and Antonio Stecher, Walmart in the Global South: Workplace Culture, Labor Politics, and Supply Chains (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018); Gary Gereffi and Michelle Christian, “The Impacts of Wal-Mart: The Rise and Consequences of the World’s Dominant Retailer,” Annual Review of Sociology 35, no. 1 (2009): 573–91; Adam Levy, “Walmart’s Lead in Groceries Could Get Even Bigger,” The Motley Fool, October 11, 2018; Nelson Lichtenstein, ed., Wal-Mart: The Face of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism, 2006; Bethany Moreton, To Serve God and Wal-Mart: The Making of Christian Free Enterprise, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010); Sandra Mottner and S. Smith, “Wal-Mart: Supplier Performance and Market Power,” Journal of Business Research 62, no. 5 (2009): 535–41; Bob Ortega, In Sam We Trust: The Untold Story of Sam Walton and How Wal-Mart Is Devouring America, 1st ed. (New York: Times Business, 1998).

September 4, 2024

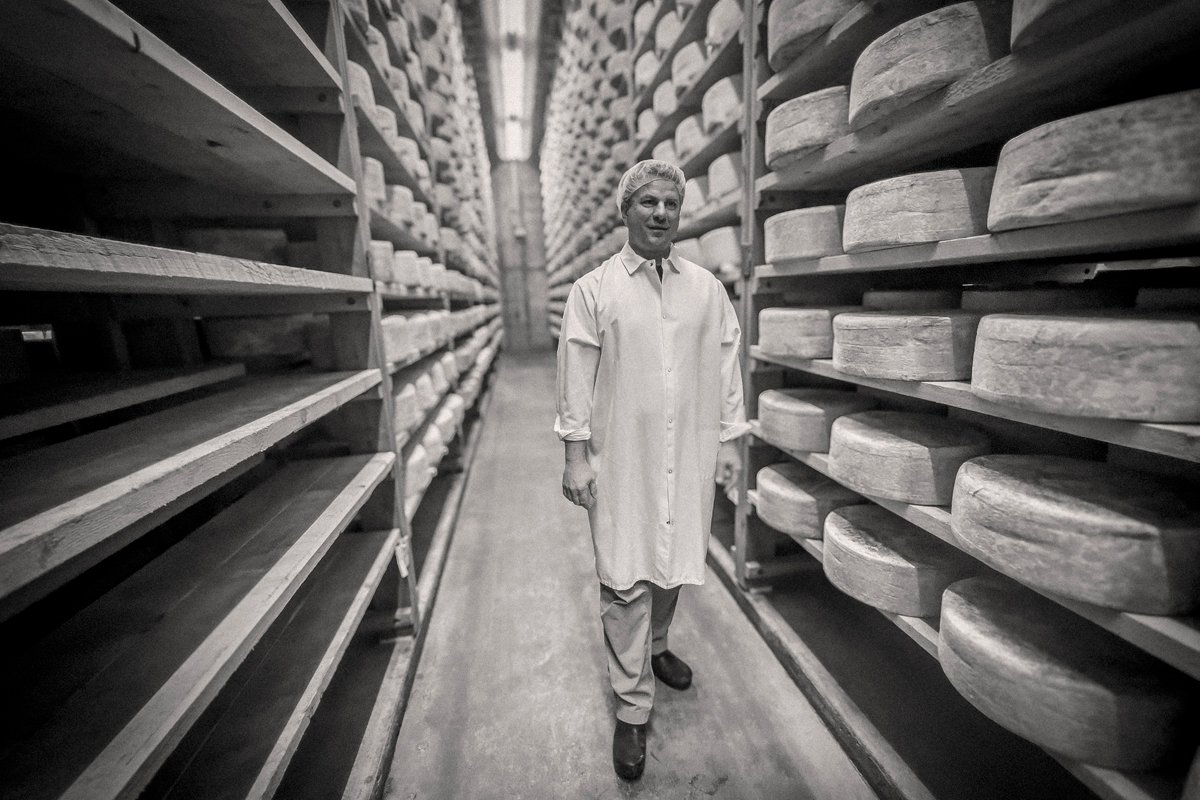

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.