Robyn Metcalfe, the producer of a new, award-winning documentary, explores economics, biology, and mortality in an attempt to understand why people are so devoted to making cheese.

Robyn Metcalfe, the producer of a new, award-winning documentary, explores economics, biology, and mortality in an attempt to understand why people are so devoted to making cheese.

July 30, 2024

A woman in Egypt demonstrates a traditional cheesemaking practice using a wooden tripod and goat skin. (Photo courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films)

“Milk is one of the simplest things in nature,” says Jim Stillwagon, an eccentric cheesemaker standing in his cluttered kitchen somewhere in the Pyrenees. “When a child vomits on your shoulder, those are the earliest vestiges of cheese.”

Stillwagon’s strange philosophical musings on curd set the tone for Shelf Life, a new documentary about the parallels between cheese aging and human aging. Produced by Robyn Metcalfe and directed by Ian Cheney (whose films include King Corn and The Search for General Tso), Shelf Life premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in June, where it won the award for Best Cinematography in a Documentary Feature.

Filmed in more than six countries over three years, Shelf Life takes us inside the work spaces of artisan cheesemakers and specialists to observe them at their craft: through the halls of underground cheese vaults in Vermont. Under the microscope with a cheese microbiologist in California. Behind the scenes of the World Cheese Awards in Wales. Into a children’s classroom in Japan for a cheese-making lesson. And to the cheese-laden dining-room table of an award-winning cheesemonger in Chicago (see “Five Questions for Alisha Norris Jones,” below).

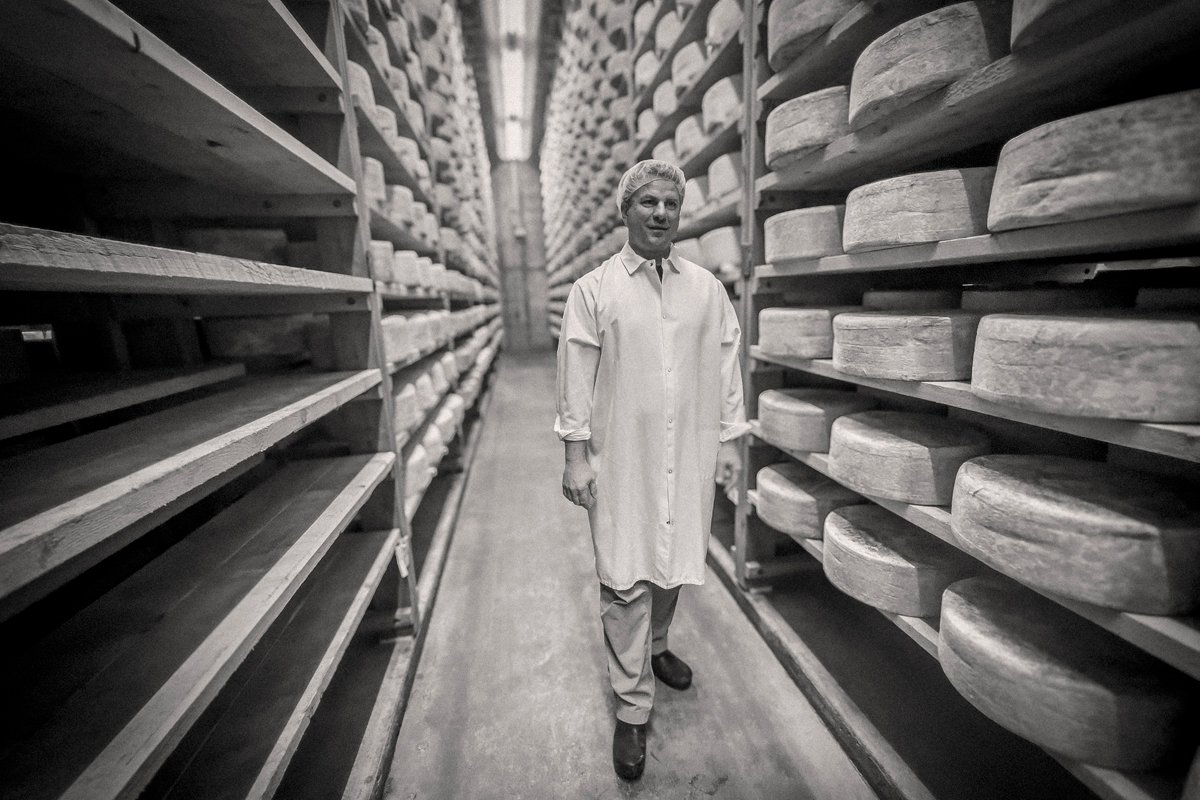

Cheesemaker Jim Stillwagon in his kitchen somewhere in the Pyrenees. (Photo courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films)

Wonderfully diverse in scope, we even get to visit an archeologist’s dig site in Egypt to learn about cheese in the afterlife, observe a traditional hand-pulled cheese practice in Tbilisi, Georgia, and descend into the shadowy basement stacks of a cheese librarian in Switzerland. Metcalfe calls this remarkable cast of characters “the poets of the cheese business.”

Shelf Life captures the vast and complex universe of cheese, acknowledging its place in the food system without getting into its politics—even when there’s a lot to say: The global cheese market is estimated at around $187 billion, according to one report, but this monetary worth comes with a sizable carbon footprint. According to a joint study by the Environmental Working Group and the firm Clean Metrics, dairy-based cheese is the third-highest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, trailing behind beef and lamb.

Some have advocated for vegan cheese as a potential solution to environmental troubles. But dairy-based cheeses play an important role in local economies and culinary traditions worldwide, enriching people’s stories and ways of life—something Shelf Life celebrates.

Although film is a relatively new medium for Metcalfe, her connection to the food industry goes back to her grandfather, Roy Diem, who worked with entrepreneur Bob Wian to build the first Bob’s Big Boy. Metcalfe grew up spending time at the restaurant, famous for its double-decker hamburger. She went on to study historical food systems at Boston University, where she earned her Ph.D., and taught modern European food history at the University of Texas, Austin. At one time, she conserved rare breeds of livestock in Maine.

Metcalfe has authored several books on the food supply chain, including Food Routes: Growing Bananas in Iceland and Other Tales from the Logistics of Eating (featured in Civil Eats’ 2019 summer book guide). She also founded Food+City, a nonprofit storytelling platform that delves into how cities are fed, and the Food+City Challenge Prize, a pitch competition funding food-tech startups around the world.

We spoke with Metcalfe recently about why she made the documentary, the future of vegan cheese, and how aging builds character both in cheeses and humans.

What inspired you to make a documentary about cheese—and why now?

The first urge to pursue this subject came from an unanswered question I had as I finished a book called Humans in Our Food. My interest in food, oddly, is not so much about the food; it’s about the systems that bring the food to the table. Often, they feel industrial and disconnected from humans.

One of my curiosities was, what are the food stories we’re not hearing? Who’s missing and unseen? I sensed that it was the people building pallets, working in food service, driving trucks, packing, and all of that stuff. I wondered if what we imagine about them is true—for example, that they’d all rather be doing something else. Or that they’re working for very little money, are pretty much exploited, kind of a sad picture, and not very smart. Some people think, “Well, if you were really smart, you would not be doing that work.”

What I did [for the book] was travel all over the world and look at a really simple dish, like a slice of pizza in New York or a rice ball in Japan. Then, I went to see who brought those things together. In doing so, the answer I got was, these unseen people are aspirational. For many immigrants in particular, it’s the way they get in and up and move onward. Some of them, surprisingly, love their jobs. Not all of them, but the assumption was so much one way, and I discovered it’s much more nuanced. One group I was really curious about was affineurs, people who work in caves. [You] might be familiar with going through a winery and seeing people who age wine, but not many people know who’s in caves aging cheese.

The second thing is that, in becoming older, I was really put off by the conversations that people wanted to have with me even a decade ago, which were, “Oh, are you still doing X?” It was all about decline and being careful and not taking any risks and certainly not building up, but designing down. It was disturbing to me. This is not what anyone wants to hear. And how much of it is a self-fulfilling prophecy, after all?

So, I’m holding this thought about how cheese ages and I thought, “I wonder if we can learn something about aging a cheese, which gets better over time or transforms [and becomes] what it wants to be in terms of character. Might we push back on this human conversation of decline?” Those two things are why I chose this subject. It wasn’t because I was a cheese lover who wanted to make a film about cheese and found a way.

Did making ‘Shelf Life’ turn you into a cheese lover?

At one point, I got a cheese certificate at Boston University because that’s how you learn about things. But if someone said to me, “Robyn, what’s the difference between these two blues?” or asked me to tease out all the different flavor molecules, I would be absolutely helpless. [But cheese is] a wonderful lens to look at life.

A cheese expert feels the rind that develops during the aging process. (Photo courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films)

What were some challenges you faced when filming?

It was a challenge getting [the cheesemakers] to talk about aging. I mean, how many people do you know who like to talk about aging? People, especially younger generations, want to be relatable and supportive, and they’re curious about being older, but it’s an awkward conversation.

(Instead,) everyone wanted to share their cheese [process]. We would get responses like, “Thank you for contacting us. This is how we make our cheese.” But we weren’t actually that interested in the how but more the why. That was very hard, because people are over the moon about cheese and want to talk about it. So, we spent more time getting to know our characters before they felt they had told us their story about cheese and would speak to us about other things.

Did you learn anything new or surprising from the conversations about cheese and aging?

Absolutely. There were a lot of really fun little paradoxes. Initially, we talked to a cheese-making nun who was featured in a New Yorker article [but didn’t make it into the film]. She had a very interesting spiritual approach to what’s going on with cheese. I was really surprised to see how you could draw a metaphor about cheese as a body. Generations of microbes transform the cheese. They eat the cheese, then they die, and leave it for the next generation of microbes . . . changing the landscape of that cheese as it develops into its character.

Also, I appreciated cheesemaker Mary Quicke’s comments about multiple peaking. People talk a lot about how I’ve “passed my peak,” “I’m not in my prime,” or “Are these the sunset years of my life?” I was surprised by her clarity and understanding that you have a lot of peaks, and you’ll have more peaks. There’s not a limited supply of peaks; it’s just a limited imagination.

Were any of the people you interviewed for the film concerned about climate change?

Some people were attaching sustainability to their farming practices—for example, Jasper Hill, in Vermont. But some of the cheese companies and cheesemakers we spoke to are so small-scale that, in most cases, climate concerns never came up. Jasper Hill uses milk from, shall we say, a largish dairy and sort of sits on the edge of artisanal and scale. That’s the conundrum, isn’t it? If you want to have good food available at a low cost to as many people as possible, then you have to get bigger. In Shelf Life, you can see that Jasper Hill already has a robot flipping cheese.

A quality control group in the underground cellars at Jasper Hill Farm in Vermont. (Photo courtesy of Wicked Delicate Films)

As a historian, were there specific experiences or people you encountered while filming that stuck with you more than others—for instance, the notion that cheese, for Egyptians, was a food they envisioned in the afterlife?

I could relate to the archeologist in Egypt trying to read artifacts and divine a story from them. Historians often don’t have the actual pieces of things and are always groping and learning how to tell the story. I was surprised to hear about the Egyptians’ concept of cheese, because you don’t read much about that.

I was fascinated by the use of old historic buildings being used to age cheese, like old breweries, for example, and some of the bunkers in Europe. Or weird places like subway halls. These repurposed spaces bring up a terroir sort of conversation about the minerals, the humidity, the bacteria, and all of that. I’m not in the cheese business, but all these moves for new sanitation standards—removing the bacteria and original wooden shelves where cheese has aged—are disheartening, because often it’s that magic elixir of all those things that make cheese special.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.