Project 2025 and the Republican Study Committee budget both propose major changes to how the government supports commodity farmers. They might face strong opposition from ag groups and their farm constituents.

Project 2025 and the Republican Study Committee budget both propose major changes to how the government supports commodity farmers. They might face strong opposition from ag groups and their farm constituents.

July 22, 2024

A drone photograph of a corn field in Madison County, Ohio, with a grain silo in the background. (Photo credit: Hal Bergman, Getty Images)

David Andrews’ farm is about nine miles away from the small, aptly named Iowa town of State Center. The 160-acre farm has been in his family since 1865, and Andrews grew up there.

Despite the landscape’s signature flatness, his land “rolls a little bit,” he said. So, 30 years ago, he decided to plant 60- to 100-foot strips of tall grasses within and along the edges of fields to prevent erosion. To pay for it, he enrolled a total of 14 acres, made up of those strips, in the federal government’s Conservation Reserve Program (CRP).

Through CRP, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) pays farmers not to farm on less-productive parcels of land, often in areas that are corn and soy fields as far as the eye can see, to be left alone to reduce runoff, improve biodiversity, and hold carbon. “It’s a great program, and a lot of these farms have some marginal ground on them that would be better off in CRP than growing crops,” Andrews said.

Project 2025 proposes eliminating CRP. The Republican Study Committee proposes ending enrollments in the program, as well.

As of March 2024, the most recent month for which data is available, more than 301,000 farms had close to 25 million acres enrolled in CRP; that’s a lot of acreage, but it represents less than 3 percent of U.S. farmland.

Project 2025, a conservative Republican presidential transition blueprint spearheaded by the Heritage Foundation, proposes eliminating CRP. The Republican Study Committee (RSC), an influential caucus of House conservatives, proposes ending enrollments in the program, as well.

It’s just one of several cuts to federal programs serving commodity farmers that Republican operatives and lawmakers have recently proposed in policy documents. Project 2025 also proposes reducing crop insurance subsidies and “ideally” eliminating commodity payments altogether. The RSC’s budget, meanwhile, proposes putting new limits on commodity payments, reducing crop insurance subsidies, and ending enrollment in another popular conservation program called the Conservation Stewardship Program.

While cutting government spending may seem like a run-of-the-mill party goal, many of these programs have long been politically sacred in farm states. If implemented, the plans could transform the nation’s safety net for farmers growing corn, soy, and other row crops.

Most Washington insiders say that’s unlikely to happen and point to the RSC-heavy House Agriculture Committee’s recent farm bill draft, which puts more money than ever into commodity programs and leaves crop insurance intact. Plus, the most powerful groups representing commodity crop interests—the American Farm Bureau and the National Farmers Union—both typically lobby hard to keep farm payments flowing.

But while conservative advocacy groups and far-right Republicans have unsuccessfully proposed similar cuts in the past, Republican politics have shifted further right in the age of Trump, and fiscal conservatives wield increasing power within the party. More than 83 percent of House Republicans are now members of the RSC, compared to about 70 percent in 2015. Former RSC chair Mike Johnson (R-Louisiana) is still a member—and is now the Speaker of the House. On a 2018 panel, he said the RSC is “now mainstream.”

“I don’t think we’re going to go to a ‘no government intervention in agriculture’ approach. It’s just not likely, but it’s certainly the dream of every conservative agriculture prognosticator.”

In early July, Trump attempted to distance himself from Project 2025, but many of its architects are former Trump administration officials and have worked on the party’s 2024 platform. The Heritage Foundation claims that during Trump’s last term, he embraced two-thirds of their policy proposals within his first year in office. A spokesperson for the Heritage Foundation declined a request for an interview on Project 2025.

“I think it’s more likely that [elected Republicans will] just do what the commodity groups and Farm Bureau want,” said Ferd Hoefner, a policy expert who has worked on nine previous farm bills and is now a consultant for farm groups. “I don’t think we’re going to go to a ‘no government intervention in agriculture’ approach. It’s just not likely, but it’s certainly the dream of every conservative agriculture prognosticator.”

With so many competing interests at play, the party’s true plans for agriculture are as muddy as an unplanted field in spring. And with Trump leading in the polls after a shocking few weeks of politics, anything now seems possible.

Andrews got out of farming in 1999. His own operation had been diversified, with cows, pigs, and various grains and alfalfa grown in rotation. But when he hung up his hat, he rented the land to a farmer who was—for better or worse—following the crowd.

“He put it all in corn and soybeans, which is natural. That’s what everybody does nowadays,” Andrews said. But CRP had worked so well for him in creating the erosion control strips, he decided to enroll nearly all of his acres for a time. “When I moved back to the area, I told him that I thought the farm needed a rest, because continuous corn and soybeans is very hard on the organic matter. I told him I was going to put it in CRP, and he said he didn’t blame me. That’s what I ended up doing.”

CRP enabled Andrews to preserve the land, restore its fertility, and sequester carbon, because instead of a farmer paying him to rent the cropland, the government paid him—less, but enough—to fallow it. But the program has long been a target of conservatives as an example of wasteful spending. Project 2025 proposes eliminating it entirely, while the RSC would prohibit new enrollments in both CRP and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP).

CSP pays farmers to implement conservation practices on land they are actively farming. The program is so popular that even after the Biden administration added money to the pot through the Inflation Reduction Act, only 40 percent of applications were funded in 2022.

Jonathan Coppess, the director of the Gardner Agriculture Policy Program at University of Illinois, said that while he doubted Republican lawmakers would be able to eliminate CRP altogether, they could slowly gut the program in the same way that some have weakened CSP over the last decade. Initially, CSP was capped based on acres, and lawmakers began cutting the acreage cap. Then, they changed the structure to a funding cap, which further shrank enrollment. The changes effectively cut funding for the program in half between 2008 and 2023.

Most conversations about conservation funding right now are focused on Republicans’ efforts to strip the focus on climate-friendly practices from extra conservation money provided by the Inflation Reduction Act.

“It can be kind of a death spiral type thing, where fewer farmers can get the funds, so the Congressional Budget Office projects less spending, so the baseline shrinks,” said Coppess, who previously worked on federal farm policy as a Senate legislative assistant and as administrator of the Farm Service Agency at the USDA. “Eventually that becomes self-defeating for the program, because farmers are angry because they spend all this time signing up and they don’t get in. So, the farmers turn on it and you can slowly kill off the program over time that way, because it loses its political support.”

The current House draft of the farm bill includes some small tweaks to CRP, but it’s unclear what the impacts of those changes would be. Instead, most conversations about conservation funding right now are focused on Republicans’ efforts to strip the focus on climate-friendly practices from extra conservation money provided by President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act.

The Republican plans to cut environmental funding—especially for climate projects—are to be expected. But nowhere is the tug-of-war between fiscal conservatism and farm support more apparent than in their proposals for the future of commodity programs, which essentially pay crop farmers when prices fall beneath a certain level. Those programs primarily benefit growers of corn, soy, wheat, cotton, and a few other commodity crops. But because so much acreage is devoted to those crops, the groups that represent their interests, like the National Corn Growers Association and the National Association of Wheat Growers, hold considerable sway in D.C. And most Republicans (and Democrats), especially in farm states, generally try to court them.

However, over the past few decades, progressive Democrats and farm groups such as the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, Farm Action, and the Environmental Working Group (EWG) have called attention to the fact that the largest, wealthiest farms have received close to 80 percent of the nearly $500 billion paid out between 1995 and 2021. As a result, they’ve fought for payment caps within the programs as a way to limit spending and distribute funds more fairly.

Surprisingly, the RSC budget does something similar by proposing that only farms with an adjusted gross income below $500,000 receive payments. “This was a policy proposed in the FY 2021 Trump Budget and would ensure that commodity support payments are going to smaller farms that may struggle obtaining capital from private lenders,” the RSC budget reads. Project 2025 goes even further and proposes “ideally” eliminating commodity programs altogether.

But when House Republicans released their latest farm bill draft, it included increases to commodity payments, at a projected cost of an additional $50 billion. In other words, they veered in the exact opposite direction.

In response, the Heritage Foundation has been pushing back on the spending bump, in conjunction with other conservative think tanks, as well as the progressive EWG.

The unlikely policy alignment is politically convenient on this one point, but in the end, the two sides have differing goals. The progressive groups want policymakers to shift funding away from commodity programs into more funding for conservation, research, local food, and specialty crops; the conservative groups just want to cut spending, period.

“Every farm bill, hope springs eternal that there will be a left-right coalition that can win some major changes,” Hoefner said. “There have certainly been many tries at that,” he added—and they haven’t stuck yet.

Another issue that’s kept those groups far apart is ethanol, which many progressive groups see as a false climate solution. Traditional farm groups, on the other hand, fight like hell to keep in place the Renewable Fuel Standard—the policy that sets a minimum amount of ethanol required in gas and other fuels. The RSC budget proposes eliminating the standard altogether.

“There’s way more interest in that issue among commodity groups than what happens in the farm bill,” Hoefner said. It’s been a sticky issue for Republicans in the past. Florida Republican Ron DeSantis once supported eliminating the standard, until he tried to run for president. Trump boasts often of his support for ethanol, but his administration exempted more than 30 oil refineries from the standard, allowing them to avoid selling ethanol, angering commodity groups.

Some of the disconnect between Republican ideals that point toward farm program cuts and what gets into policy may simply be attributable to the reality of politics, Coppess said.

“There’s the cognitive dissonance kind of challenge that we see with any heavy focus on budget issues,” he said. “So, we wanna cut spending, we wanna balance the budget . . . and that always is easy to say and sounds good, but it is really difficult to do in practice, because every one of those items has a constituency. It is a difficult governing reality.”

As the weather has become more unpredictable due to climate change, for example, crop insurance has become a bigger political priority for farm groups and also the most expensive farm program, outpacing commodity spending.

During farm visits, Johnson said, “the most common thing we heard from producers was, ‘Don’t screw up crop insurance.’”

Both Project 2025 and the RSC budget propose reducing the portion of premiums paid by the federal government so that farmers shoulder more of the cost, while the RSC budget proposes a crop insurance subsidy cap of $40,000 per farmer. Project 2025 says farmers should not be allowed to get commodity payments if they get crop insurance subsidies.

All of those cuts are at direct odds with the powerful National Farmers Union’s 2024 policy book.

And at a panel on the National Mall hosted by the Association of Equipment Manufacturers in May, House Ag Committee members Dusty Johnson (R-South Dakota) and David Rouzer (R-North Carolina) both seemed to be reading from that policy book, despite the fact that both are members of the RSC.

During farm visits, Johnson said, “the most common thing we heard from producers was, ‘Don’t screw up crop insurance.’” Rouzer described crop insurance as one piece of a strong farm safety net. “If you want to preserve green space and rural areas, [then you need to] have a good, strong, safety net in place so that our farm families can continue to make ends meet and continue to do what they do best, and that’s feed and clothe the world,” he said.

Neither Dusty Johnson nor David Rouzer’s offices responded to requests for interviews.

Time will tell if elected Republicans will act on the farm program cuts proposed by the most conservative members of their party. While some of the dynamics of farm-state politics are longstanding, others are changing.

Hoefner points out that in the 1980s and 1990s, Democrats and Republicans both represented many districts with commodity interests. Today, it’s nearly all Republicans. But rural areas are also being hollowed out as farms disappear or get bigger, which could one day shift power away from those farm states.

Consolidation in seeds, pesticides, grain trading, and meat (which most commodity crops funnel into) has also shifted power to commodity groups. These, in some ways, represent row-crop farmers, but they are also dominated by the ag industry. As a result, some conservative lawmakers from farm states have told Civil Eats they hear from industry, not farmers.

That’s one reason both Coppess and Hoefner said what will likely happen is what usually happens: Lawmakers will put out budgets and proposals that bolster their fiscal conservative credentials but then will govern in a way that bucks those policies to keep the support of ag industry players with deep pockets. “They would never dream of saying any of those things when they’re meeting with their farm constituents,” Coppess said.

In Rep. Dusty Johnson’s case, when asked about conservation programs at the May equipment manufacturers’ panel, he answered with political dexterity, praising conservation programs but indicating he may in fact be on board with the RSC proposal to eliminate CRP.

“Conservation is critically important,” he said. “I think this farm bill is gonna acknowledge the importance of working lands conservation even more than past farm bills have. That’s not to say there’s never a role in idling acres, but, listen, we can do some incredible things with soil health, water quality, habitat, while working those lands.”

Back in the middle of Iowa, one of the outcomes Andrews is most excited about when it comes to how CRP has impacted his farm is that its effects didn’t end at the borders of his fallow fields. On his own farm, he’s reduced soil loss, built organic matter, and watched wildlife return. But it’s also improved the sustainability of the surrounding farm landscape, where most farmers are doing plenty of planting and harvesting.

“I’ve got two or three farms that their water drains onto my farm, and some of that water is carrying chemicals and nitrogen, and my land is really cleaning up their water,” he said. “I think it’s a great program . . . but there’s not as many CRP acres around as what there used to be.”

If the conservative budget hawks get their way, there could be even fewer.

September 4, 2024

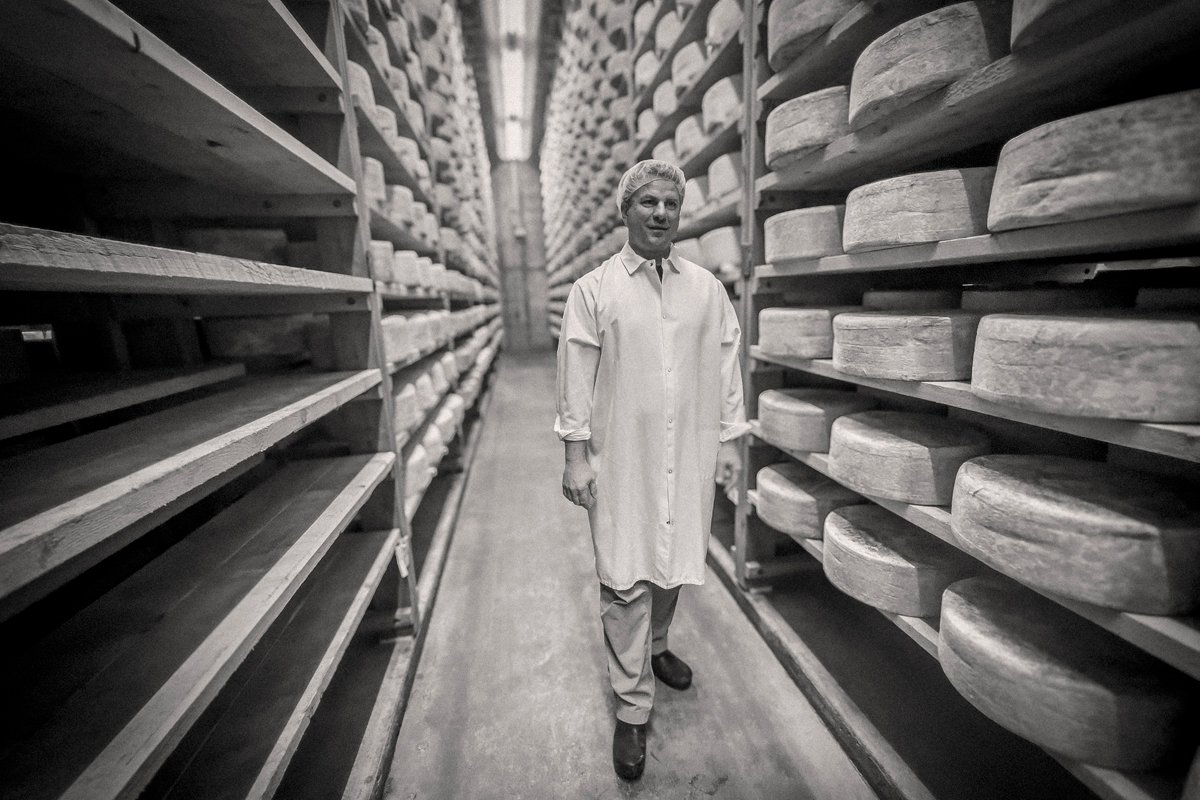

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

August 20, 2024

August 13, 2024

August 12, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.