A scientist, farmer, journalist, biologist, and community organizer reflect on the power and ongoing impact of Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book, and the work that remains to be done.

A scientist, farmer, journalist, biologist, and community organizer reflect on the power and ongoing impact of Rachel Carson’s groundbreaking book, and the work that remains to be done.

October 19, 2022

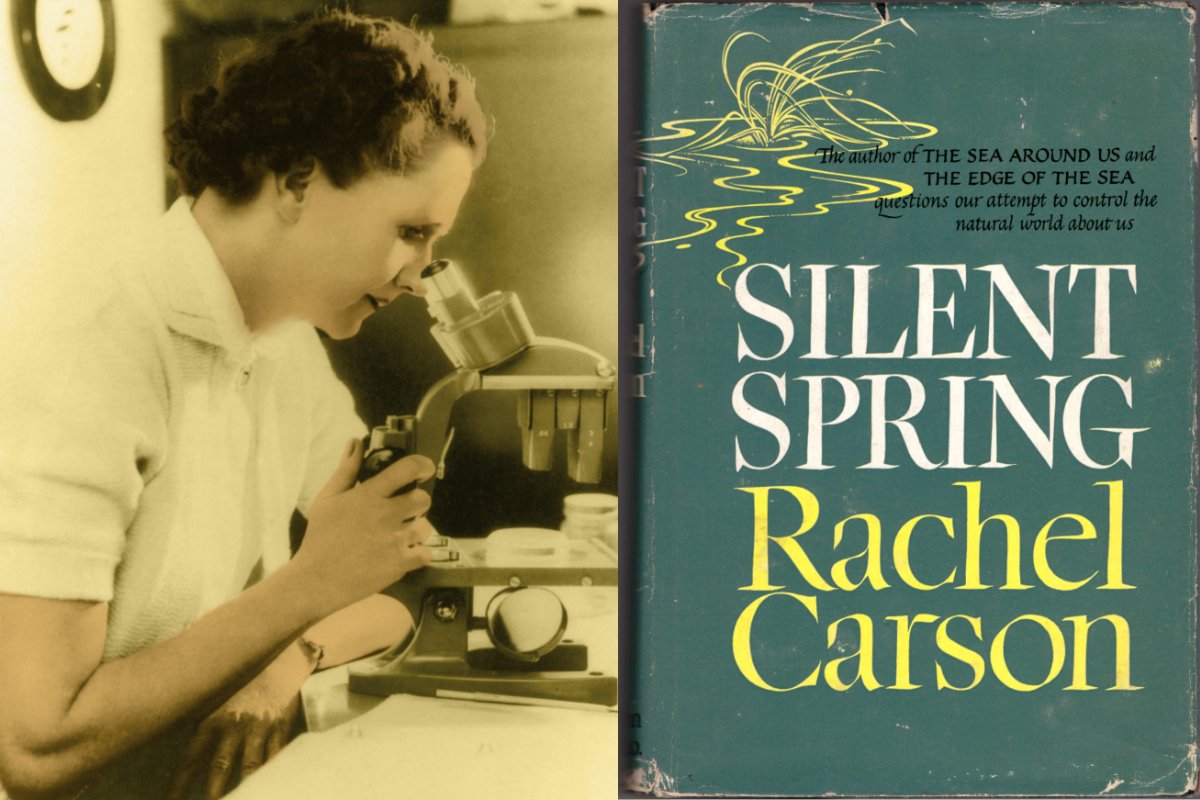

Rachel Carson photo credit: Science History Images / Alamy

In late September, California released a sobering report on the amount of pesticide residue found on produce sold in the state: Sixty-five percent had detectable levels, the highest level since the state began monitoring pesticides on food in 2012.

These findings are just the latest reminder of how prevalent these chemicals are in our food system, and they’re especially pertinent six decades after the publication of Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s seminal book about the dangers of pesticides.

“It had a radical message at the time: raising the alarm about the devastating impact of chemical pesticides and connecting those dots to the profit motive of the corporations behind them.”

Despite her warnings—and all we have learned since—pesticide use is up 81 percent in the past 35 years, with some regions of the world spiking considerably. South America, for instance, has seen an almost 500 percent jump in use during that period.

With pesticides still so rampant, what is the legacy of Silent Spring? How far have we come and how much farther do we have to go to realize the human right to healthy food, and to protect the rights of the farmers and farmworkers growing that food?

To explore these questions, Civil Eats hosted a roundtable with some of the field’s leading voices. They include Mas Masumoto, a California organic peach farmer and author; his forthcoming memoir Secret Harvests is a tale of family farms and a history of secrets. Marcia Ishii is Senior Scientist at Pesticide Action Network of North America, where she has worked for 26 years as a senior scientist. Anne Frederick is a community organizer in Hawaii, working with communities impacted by agrochemical companies’ expansion. Sharon Lerner is an investigative journalist who has reported on pesticides, chemical regulation, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Sandra Steingraber is a biologist and author, who blends her gifts as a writer, storyteller, and scientist with advocacy.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did Silent Spring and Rachel Carson’s work touch your life?

Mas Masumoto: The book touched my life directly: I grew up on a farm, in a farm community. My grandparents were farmworkers. For me, her book was a lens into the human condition that is a part of farming: It’s not just growing and producing something—it’s about what’s happening to the people on the land, too.

Marcia Ishii: I started this work many years ago, working in Thailand with farmers who were being directly exposed to chemical pesticides and witnessing the extremely aggressive marketing of pesticides by corporations and agricultural extensionists. When I read Silent Spring, I saw that Rachel Carson was connecting so many of the dots that I had seen firsthand.

It had a radical message at the time: raising the alarm about the devastating impact of chemical pesticides and connecting those dots to the profit motive of the corporations behind them.

By providing well-documented research and beautifully written compelling narratives, she raised the alarm, galvanized public outrage, and forced people to actively and vocally question the agenda behind the pesticide industry’s campaigns. In that sense, Carson played a pivotal role in igniting the environmental movement, with many connections to the issues I was seeing in Thailand, and that Pesticide Action Network activists decades later are still documenting and mobilizing around at the global level.

Sandra, you edited a Library of America volume of Silent Spring, including letters that Carson wrote to her fellow scientists at the time she was working on her manuscript. What did that project teach you about the book’s insights?

Sandra Steingraber: You can see her mind working in those letters. She’s trying to put this jigsaw puzzle together of all the scattered pieces of evidence showing the risks and harms of pesticides—and especially the class of today’s chemicals we call organochlorines, known now to siphon their way up the food chain, concentrating as they go, as hormone-mimicking chemicals linked to cancer. Back then, without a cancer data registry or pesticide registry, Carson was blind to a lot of data we have now. Yet by piecing together all these different studies, she was able to see the harm and mechanisms by which the harm was created.

“Carson is definitely a scientist, but she’s also an amazing reporter, someone who stuck her neck out. And it always strikes me reading Silent Spring how much she cares about what she’s writing about—it bursts out of her. She’s angry.”

She was really interested in the fact that most of the crop dusters had been military planes in World War II—pesticides were products of the war as well. DDT came home as a war hero. It stopped typhus and malaria epidemics and saved the lives of our troops, and the chemical companies were contracted to make great quantities. When we dropped the atom bomb on Japan, ending the war more quickly than we thought, the stockpile of chemicals remained. Madison Avenue was put to work developing ad campaigns to turn these poisons—for which there was no advanced safety testing because it was done under wartime secrecy—into pesticides and broadcast spraying them.

Carson looked at emerging data showing high rates of diabetes among crop dusters, and then looked at what was happening to roosters who were exposed to DDT: The combs on their head were becoming more feminized. From those little bits of data, she was able to correctly deduce that DDT and other organochlorines were what we would call today endocrine disruptors. They were having an effect on the endocrine system—and she was absolutely right.

Anne, from your vantage point in Hawaii, what are you seeing in terms of the pesticide impacts Carson warned us about?

Anne Frederick: My way into this work has been through the stories of folks living on the west side of Kauai, the island where I live. It was in the 1990s and 2000s as the last sugar and pineapple plantations were moving overseas, and agrichemical test fields were being planted in their place. There had been more than a century of scraping away the biodiversity in Hawaii to make way for endless seas of sugar and pineapple, so it was easy for the agrichemical industry to step into the footprint left behind [and grow crops that were genetically modified to withstand large quantities of pesticides]. These fields were adjacent to schools, homes, and the largest concentration of Native Hawaiian residents on island. I started hearing stories from communities living near these test fields, like that of a dear friend who lived 100 feet from one; she and her daughters started developing asthma, other illnesses. Stories like hers drew me in.

I didn’t have a history of working on pesticides, but as a community organizer I wanted to apply my skills to this work. We started by asking for basic transparency and policies like buffer zones between test fields and schools and hospitals. It has taken us decades to win even some of the most basic protections for these communities. When I look at this book from 60 years ago, and all the data that’s followed since, I’m still struck by what an uphill battle it is to get even modest protections and transparency. Part of the reason is because of the hold industry has on our local government. Realizing that has informed our approach of political power building and identifying how we can address regulatory capture and corporate influence in our local government—and seeing that as a root cause that has allowed this harm to go on for so many years before it was addressed.

Sharon, as an investigative journalist, can you share an example from your reporting of how you’ve seen the industry shirk the kind of regulation that might have protected us more?

Sharon Lerner: Yes, I come to Rachel Carson as a fellow reporter. Carson is definitely a scientist, but she’s also an amazing reporter, someone who stuck her neck out. And it always strikes me reading Silent Spring how much she cares about what she’s writing about—it bursts out of her. She’s angry. There’s this idea that as a journalist you are balanced and unbiased, but I don’t believe we are ever not biased. I believe I do have a bias and that my bias is toward not having toxic chemicals in nature and in our bodies. I readily admit to that bias.

I have also always been struck by how much she was attacked in response to this book. Monsanto came out with its own takedown and was really awful. I’m also struck that she died of cancer, and so have many of the people I talked to as I’ve done this kind of reporting.

As a journalist, I’ve focused on pesticides, and particularly the pesticide paraquat. With a reporter from Le Monde, we looked through hundreds of internal documents mostly from Syngenta and its predecessor companies. Our story focused on an additive to paraquat that was supposed to ensure that people didn’t get poisoned with it—and it didn’t work.

In reading through those documents, you saw the evolution of the dialogue internally about pesticide regulation in the U.S. over time. When you look at some of the early documents, you can see that the executives are extremely worried about what the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] will do to them. Over time, the attitude toward the EPA changes.

“Carson articulated really important concepts in Silent Spring, including the concept of chemical trespass against our bodies, land, water, and air.”

I ended up writing a piece that tried to answer the question of what happened between 1970 (i.e., the founding of the EPA) and today, when we have 16,800 pesticide products on the market. The EPA is [now] not so much a regulator to be feared, but a partner in the production of thousands of pesticides—there has been a real joining forces between industry and EPA. Part of that is the revolving door with regulators going into the pesticide industry. One of the things I showed was that, since 1974, all the directors of EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs who continued work after holding that office went on to work for the pesticide industry in one way or another. That’s part of the problem.

That paraquat story was chilling. Paraquat is one of the most highly toxic pesticides—a teaspoon of it will kill you, right?

Lerner: Yes, and for that reason, it’s banned in many countries but still in use in the United States. It’s also believed to be linked to Parkinson’s [disease]. There’s litigation now about that—and whether folks can prove in a courtroom that it causes Parkinson’s.

Masumoto: I think part of the power of Silent Spring is the legacy it leaves behind. When I first came back to the farm, I started farming organically, but we were still using some chemicals on part of the farm, and my dad broke out in a rash. He went to the doctor, and his answer was simply: “Stay out of the fields.” You don’t tell a farmer to stay out of his fields. It made me rethink how we were doing things and question how we farmed. It made me realize there’s a human impact of how we do our work—the idea that we take farming practices personally.

Where have we seen the most progress since Silent Spring?

Lerner: There is greater awareness of how important it is to eat foods that weren’t grown with pesticides: organic food. In the seven, eight years I’ve been reporting on this, there’s a change in how people receive this and a greater level of interest. I cannot provide any cheer on the regulatory side.

Steingraber: I appreciate everything that Sharon said. I would never want to bright-side this: We’re in a world of serious harm here. These institutions remain, though some are vestiges of their former selves. But their persistence is because Carson’s words also fomented a populist environmental movement.

Narrowly speaking, Silent Spring is about the toxicological properties of 19 pesticides, yet it was written in such a way that it rocketed to the top of the best-seller list when it was published in September 1962.

This was at the beginning of the Kennedy administration. It caught his attention, which caught the attention of the press and emboldened the media to stand up against the disinformation campaign that the chemical industry almost immediately—even before the book was published—started churning out [responses]. The New Yorker serialized her work. [The magazine] was threatened by the chemical industry, but it just shrugged off the threats of a lawsuit and published it anyway; so did Houghton Mifflin.

Kennedy commissioned an advisory group that wrote a report vindicating her book, which triggered a public hearing where she testified before the Senate. It opened a space in the culture, then all kinds of things happened, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, all these monumental pieces of legislation. The least well-known but maybe the most important was NEPA [the National Environmental Policy Act], the federal statute that requires that any time a government proposes to do something with environmental consequences, the public gets to weigh in, stakeholders have to be consulted, and the government has to take into account what they say.

Recently, we’ve seen this amazing thing happen in Washington, D.C., which is a direct legacy of Rachel Carson: There was this attempt to do so-called “permitting reform” and weaken these regulations for being too cumbersome. Led by Senator [Joe] Manchin [D-West Virginia], with his connections to the fossil-fuel industry, the idea was to throw key provisions of NEPA out the window. The consequence almost surely would be more pipelines built faster, environmental justice would go out the window, public health of communities would be impacted, as well as the climate consequences. But there was strong enough outcry, led by communities of color and people on the ground in Appalachia, where the Mountain Valley Pipeline was supposed to run through, that permitting reform got thrown out. This political power, which prevented Chuck Schumer from moving forward with Joe Manchin and throwing out this really important regulatory framework, is a direct result of Silent Spring. I consider it a kind of indirect victory for Rachel Carson.

Ishii: Carson articulated really important concepts in Silent Spring, including the concept of chemical trespass against our bodies, land, water, and air. She articulated this important concept of the public’s right to know, and not only in biological and scientific terms, but also what’s going on politically behind closed doors. Connecting that and looking at past decades of global pesticide activism and advocacy, we do see a tremendous amount of progress since PAN was founded 30 years ago in Malaysia at a gathering of activists looking at health and environmental harms and injustices of the global pesticide trade.

“It has become politically untenable to spray pesticides next to schools and homes in our community, which is a huge shift.”

We’ve fought for and won a 1,000 percent increase in bans of the worst pesticides. But more than just banning individual pesticides, we have been able to push on the public’s right to know not only what toxins we’re being exposed to, but also governments’ right to know about and refuse the importation of pesticides that have been banned or restricted elsewhere. After 20 years of advocacy, we got the Rotterdam Convention on prior informed consent that provides the right of country importing pesticides to know and then decide to refuse the import. That’s a huge success.

We also got the Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants established to phase out chemicals, including a number of pesticides that persist in the environment, that travel far beyond where they’re used, committing chemical trespass along the way. Both of these conventions have been ratified by over 170 countries.

Just this year, after much advocacy by our partner, PAN Germany, the German government publicly committed to prohibit the exporting of pesticides banned at home. This legal action will come into force next year. A lot is happening, and I attribute it to the power of community mobilizing and coalition organizing, challenging corporate lies and false solutions with scientific and empirical evidence, and lifting up the voices of directly affected communities.

Implementation is always an issue. You get these laws, policies, and agreements, and they’re not always implemented on the ground. It’s not only the USDA and EPA that have been captured by corporate influence, but the United Nations, too. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) a couple years back announced its intention to formalize a partnership with Crop Life International, the pesticide industry trade group. After mobilizing hundreds of thousands of voices of opposition, the FAO said they are not moving forward with the partnership, but they’re also not really canceling it; it’s just sort of sitting there behind a curtain.

I also have to say despite all this amazing work, pesticide use, profits, and poisonings are all increasing. This is a huge problem. PAN recently investigated pesticide poisonings globally and found that over 385 million people are poisoned from acute unintentional poisonings every year. That’s 44 percent of the 850 million people involved in agriculture. This is a big jump from the often-cited 1990 figure of 25 million.

The problem hasn’t gone away. We can’t just ban, restrict, and phase out. We must do that, especially highly hazard pesticides, but we need to build solutions on the ground. That’s where I’m so excited by local agroecology movements, the work of farmers like Mas who are creating viable, resilient systems on the ground, who are building bridges between rural and urban communities.

Anne, can you speak to how much you’ve been able to accomplish in Hawaii and how much are you’re still up against?

Frederick: I think about my friend who lived 100 feet from test fields—her, her daughters, and community are safer these days. It has become politically untenable to spray pesticides next to schools and homes in our community, which is a huge shift. I see tangible improvements to people’s lives. The banning of chlorpyrifos is another [win], especially because it was so heavily used, particularly on the west side of our island.

“Reframing—that’s what good stories do. Stories reframe things, rewrite things, and allow people to reflect. Suddenly the foods that they eat, it’s like, ‘What are we consuming?'”

One thing that gives me hope in our movement is the groundswell of activism that started around the acute exposure incidents in schools, when teachers and students were hospitalized, and that it has really evolved. There’s still very much a grassroots movement in the streets, but there’s also a political savvy that has evolved, too. A lot of the folks who first mobilized around these basic protections have gotten involved in local politics. For example, the Maui County Council is majority progressive for the first time in the political history of Hawaii. They’ve been able to pass the most stringent organic public land management ordinance. There’s a lot of great news at our local level, which we know is also threatened by preemption at the federal level.

Mas, are farmers more open to the lessons of Silent Spring? What do you see as its legacy for farmers?

Masumoto: Farmers are obviously close to working with nature and understanding things like climate change. What Silent Spring showed was the power of stories, and Carson captured the story of pesticides for a broader public, but it penetrated rural sectors and farmers, too. Out of the book was this idea that there are new directions we have to start taking. I’m seeing more and more farmers talking about and looking at soil life and biology. Dirt isn’t just dirt and lifeless. They’re starting to look at it through a different lens—that’s a quantum leap. That’s very important, because suddenly you see life in the soils, you see life around us, we’re growing life! With that comes this idea that our goal as farmers is not to kill what we don’t see and don’t know.

I also think a younger generation is seeing food through the lens of how it is grown and who grows it. For an older generation, it’s looking at food as medicine and realizing it’s not just a matter of taking another pill—it’s about the foods we eat.

Reframing—that’s what good stories do. Stories reframe things, rewrite things, and allow people to reflect. Suddenly the foods that they eat, it’s like, “What are we consuming?” Boy, that’s a huge leap to start thinking, “Who grows it, how do they grow it, what ways do they grow it, and what goes into the food?”

The public is beginning to see, feel, and taste the environment in the foods we eat. And that’s a huge shift as opposed to the old model—you just go to the grocery store and you don’t care where it comes from. That makes me very, very optimistic.

What’s the biggest takeaway you want people to hold from Silent Spring?

Steingraber: The human rights approach. Carson was clear that people affected by pesticides and other harmful chemicals have the right to know and take action—and the government needs to be responsive.

Lerner: She was already onto the concern about regrettable substitutions: DDT itself was a substitute, and she was looking ahead, unfortunately, to what would be an ongoing cycle.

Frederick: The example of the courage of speaking out against a powerful industry, even when it’s uncomfortable. They’re always going to try to marginalize this work, but we need to persevere. We owe it to our communities and our planet.

Ishii: Yes to all of this. I would add Carson’s passion, joy, and love. As we organize and come together as social movements, we’re fighting the bad, but we’re also building beautiful, loving systems of mutual care and healing. This collectivist, community approach is at the heart of what we need to do going forward.

Masumoto: For me, it’s about what we can and should demand to control.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.