By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

July 6, 2022

Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane, or DDT, is a notorious pesticide that was once considered a panacea in the United States. It was unleashed with abundance from the 1940s to the 1960s, used to fight a wide range of agricultural pests and human diseases, but its toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans soon came to light, and the chemical’s use was discontinued.

While DDT has been banned in most countries across the globe (with an exception for malaria control), for five decades, it has persisted in our environment and continues to cause disease in humans and animals. Despite that, in recent years, some have been calling for more use of DDT to fight not just malaria, but also West Nile Virus and the Zika virus.

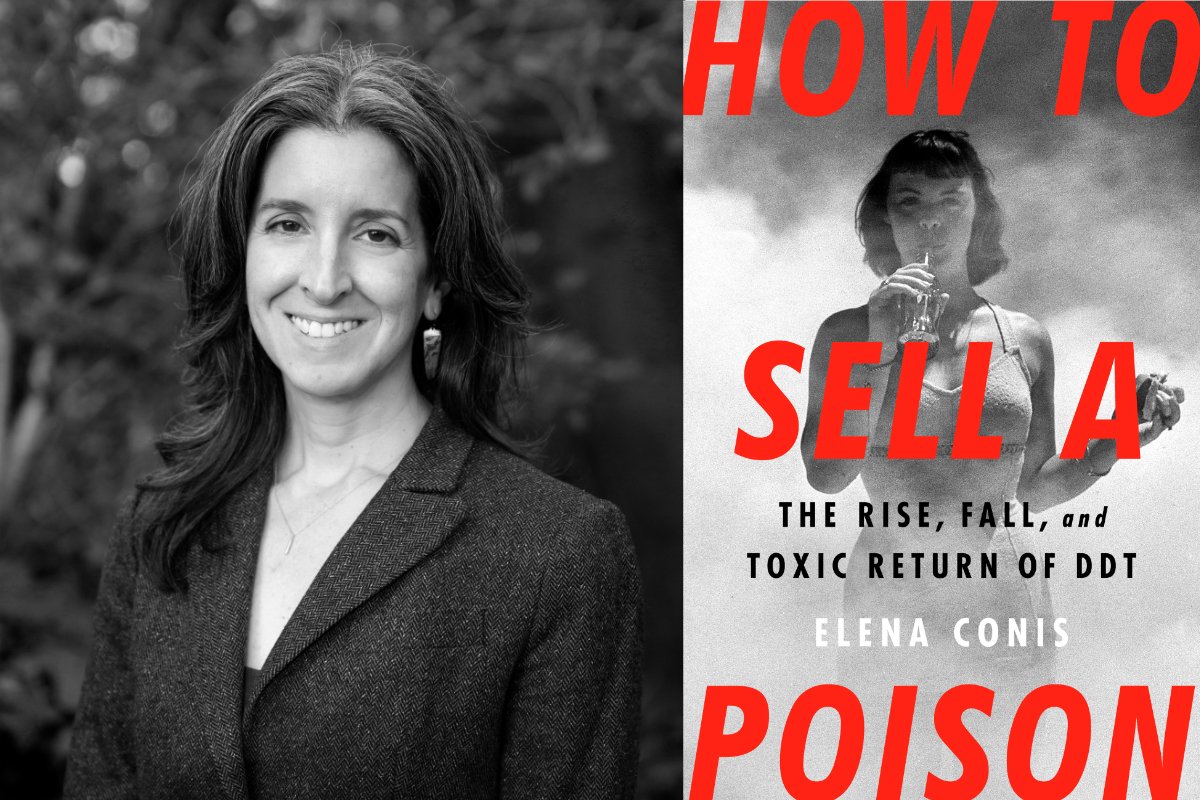

In How to Sell a Poison, historian of medicine Elena Conis traces the history of DDT, its impacts, and the implications of the shifting science. In a masterful narrative style that reads like a novel, Conis tells the stories of ordinary people and the nascent environmental movement that sought to expose the chemical’s harms. Her book offers insights about the mechanisms of science denial, disinformation campaigns, and the role of politics and other social forces in shaping a nation’s approach to regulating a toxic substance.

Civil Eats spoke with Conis about the light that DDT’s story sheds on the many other toxic chemicals used today, how social inequality, race, and environmental pollution are linked, and why the tobacco industry funded a secret campaign to bring back DDT.

Why did you decide to write a book about DDT, and why now?

I grew up in the 1980s, a decade after DDT’s ban. I knew of it as one of our most toxic chemicals. I knew that it was responsible for the loss of major numbers of bald eagles and, where I lived in New York, a loss of osprey, among other birds. Then, as a graduate student, I attended a conference where some global health experts talked about the problem of malaria getting worse, particularly in places like Sub-Saharan Africa. They all mentioned the need to bring back DDT. That alone surprised me. But what surprised me even more was that nobody else in the audience seemed to find that strange, weird, or troubling. I carried these questions around for a long time: What had happened to DDT? Had its reputation changed? Had people reconsidered how toxic it was?

Fifteen years later, I became a historian of medicine. I had been a journalist focusing on health and medicine for a while, I got my PhD in history [at the University of California, San Francisco], and found an electronic archive at UCSF that contains scanned versions of corporate documents disclosed in the mid-1990s during hearings on the tobacco industry. I stumbled upon a couple of curious documents about DDT. It turns out the tobacco industry had an expressed interest in the return of DDT. That’s when I realized the chemical had a more complicated story. It had gone from war hero to public enemy to a third act a generation later, when we completely reconsidered it. It seemed like an interesting case study for understanding how we change our minds about science, who is involved in shaping what we know, and [shaping] technology based on our scientific knowledge.

As a society, we’ve been fighting about science for the past decade or so, with many people seeming to reject accepted scientific claims. And people who believe those scientific claims feel completely frustrated when they aren’t simply accepted as a matter of fact. DDT’s story to me showed how scientific facts can change depending on the context, the questions that we ask, and the interests pursuing the answers to those questions. It seemed a helpful case study for understanding why we fight about science and what we’re actually fighting about when we do. In the story of DDT, I found that the debates about the chemical were proxy battles for struggles over gender, race, class, and the economy.

You describe in shocking detail the ubiquitous, constant, large-scale spraying of homes, fields, pets, cattle, and entire American cities with DDT. Why was this chemical so widely used?

If you could put yourself in the shoes of people who first encountered this chemical on a large scale in the ‘40s and ‘50s, you would see that the earlier generation of pesticides and insecticides—those used before DDT—were so much more toxic. They were known poisons, compounds made with lead and arsenic. It was an accepted fact that if you were going to kill insects, you would use something that was poisonous to people. DDT wasn’t toxic in the same way. Animals and people could be exposed to a lot of DDT in the very short term and they would be okay.

The fact that we had something that could kill insects and not make us sick in the short term suddenly made DDT seem like the answer to everything. People became dependent on it really quickly because they didn’t have to go to great lengths to rid their houses of ants or roaches, or their whole community of flies or mosquitoes. DDT offered a way to keep things clean, salubrious, “healthy.” At the same time, it was a way to make agriculture more profitable—because with a sweep of DDT, farmers could eliminate some of the worst pests.

Despite these benefits, other countries did not use DDT in such huge quantities. The U.S. was unique in how abundantly it sprayed the chemical, even though it had actually been developed by a Swiss chemical company. Why?

DDT’s story was woven into the story we told during and after the Second World War about how the U.S. became a superpower. Americans constantly heard about how DDT had protected our troops, prisoners of war, and refugees from malaria and other devastating diseases. The chemical, they were told, had essentially transformed the war. So, DDT was accepted as part of this bigger project of seeing ourselves as a global leader.

The big companies manufacturing DDT were also subsidized by the federal government during the war. So, they emerged bigger and more powerful than they had ever been. Combine that power with the enormous American appetite for DDT and suddenly, it was huge. It just took off.

Thousands of other chemicals have since been released on the market and the federal government regulates only a tiny percentage of them. What lessons does your book offer about the regulation of chemicals?

The first takeaway is that DDT created a set of problems that we gradually became aware of and then we thought we solved by banning the chemical [in 1972] and later through the passage of Superfund [a program of the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) established in 1980 to clean up hazardous waste dumps]. But here we are, 50 years later, and this chemical is still with us. It’s still affecting people’s health, and it’s still in wildlife, in birds, and in marine mammals, affecting their health too. It continues on in the environment, including in places we didn’t even know about or we allowed ourselves to forget about. We’ve been cleaning up DDT on land, but we recently discovered that loads of DDT were dumped into the Pacific Ocean, just off the coast of California. So, one of the big takeaways is that when we move with haste, we have no idea how long the health and environmental consequences of our technological developments are going to last.

Second, when we take steps to solve those problems, we also don’t have a good handle on the timeframe required for those solutions to be meaningful. We “solved” the problem of DDT by banning it and by cleaning up the environment. At one of the Superfund sites that I looked at, the EPA created a cleanup plan in the early ’80s that involved rerouting a river and monitoring fish over time to make sure that their DDT levels were going down. After 30 years of cleanup and monitoring, the fish had DDT levels that were considered safe [at the time], but today we don’t think that level is safe enough. The moment we create a technology or a chemical, we start running a race to understand all kinds of ways in which it’s going to reshape ourselves and our environment. We’re forever going to be playing catch up.

How did the science on DDT evolve and what are the lessons about science that this history exposed?

DDT was and still is one of the most well-studied chemicals we’ve created. It was so well-studied because it was used so extensively. During the war, men serving in the armed forces spent morning, noon, and night just spraying, spraying, spraying. They were covered in DDT all day. And everybody studied them—the manufacturers, the army—and concluded these men seemed fine. The war was over, they were discharged, and that was it. Then there were studies after the war to follow not just sprayers, but also people working in the factories that manufactured DDT. There were studies in which DDT was fed to prisoners. Typically, scientists would study a small group of men, ask a limited set of questions, and conclude that all was fine.

Then, after the war, the horse was out of the barn. Everybody knew about DDT, its formula was published, and all of the big and little manufacturers were making and selling it. There was so much research—including on DDT’s accumulation in fat tissue and in breast milk—that was published, reported, and for all intents and purposes, ignored for decades.

Over the latter half of the 20th century, we shifted from short-term toxicology studies to longer-term epidemiological studies. We also started to change the questions we asked. And we began looking at DDT’s effects in much more representative samples of the population, including women, children, the elderly, people with pre-existing conditions or diseases, and people who had been exposed to DDT in different ways and for different lengths of time. A lot of this research took place after DDT was banned, so they had to be creative about the questions that they asked. Also, the way people were exposed to DDT was shifting. During the war, people were exposed to the spray. After the war, they were mostly exposed through their diets. So, scientists had to ask entirely different questions.

We treat science as a source of concrete, unyielding, indisputable answers. But science is, in fact, a process we use for understanding ourselves and our world. And over time, that process is going to give us new kinds of information. The process itself is going to change the kinds of questions we are interested in asking, how we ask them, and how capable we are of getting certain kinds of answers. At the same time, science is social. It’s carried out by human actors. And scientists bring to this process all of their pre-existing biases, prejudices, and assumptions. If we could just acknowledge that and see it more clearly, it would help restore public trust in science.

Rachel Carson, the famed author of Silent Spring, often gets much of the credit for bringing DDT to the attention of the American public. But your book focuses on other actors, including farmworkers. How did the United Farm Workers Union (UFW) fit into the battle against DDT?

The contribution of farmworkers has not gotten nearly the amount of attention that it deserves. I came across a quote from Cesar Chavez in which he claimed responsibility for the public turn against DDT. At first, I thought, “That’s a really big claim!” But the more I read, the more I realized that farmworkers did do a lot to turn the public against DDT. There were a few instances of mass poisonings of farmworkers, and as Chavez began to organize boycotts of grapes grown in California, some of the workers asked to include pesticides on the list of demands made to growers. They publicized the fact that if you bought non-union grapes, they might have loads of pesticides on them. This was effective and got the public’s attention.

When the UFW finally got its first union win, the contract included a ban on hard pesticides, including DDT. This was one of the earliest bans of DDT in the United States. So, before the EPA banned it at a national level and before states banned it at the state level, farmworkers got DDT banned in their union contracts. This is a part of the story that has gotten lost in our focus on Silent Spring and the environmental movement.

You tell the stories of ordinary people impacted by DDT, from soldiers to housewives to farmers. Why did you choose to focus on them, as opposed to the big players?

I’ve always been interested in gaining a deeper understanding of why certain people can place their trust in science more easily than other people. We often turn to institutions and experts for answers to this question. I felt like the best way to explore it was to set the institutions aside. I made a deliberate choice to make the small farmer just as important as the chemist. It was important for me to let them all stand on level playing ground, to see their interactions more clearly and understand exactly why regular people came to the conclusions they did and took the actions they did.

Science historians sometimes point out that, years ago, science took place when people engaged in observation or experimentation right where they lived. Today, by contrast, science is far removed from where ordinary people live. As soon as DDT was released for public sale in 1945, all of these chemists got the formula and made it themselves. For example, there was a man who lived in Georgia who ran a pharmacy and he wanted to sell DDT. His daughter got the formula from a journal at the college library. She gave it to her dad, he made DDT in the lab in his garage, and then sold it in his shop. Today, this sort of thing is unthinkable [because of patenting and intellectual property rights]. This makes us dependent on experts and institutions to know what’s going on. That removal is related to the breakdown of public trust in science.

I also tried to get inside the heads of people who defended DDT. They would do things like eat DDT on camera, before a reporter on the evening news. DDT didn’t seem that toxic to them; so many other chemicals were clearly more toxic. They believed so strongly in its benefits and they thought those benefits outweighed the harms.

Your book shows how social inequity, race, and environmental pollution are inextricably linked. How were these inequalities addressed by the government, if at all?

Without a doubt, people of color were exposed to far greater amounts of DDT and for longer periods of time than white people, especially white middle-class people. So much of it was used on cotton, and in the South many of the farmers and those working in the fields were Black. But there was little attention to the implications of that fact. Studies looked at how many of the persistent pesticides were in the diets and the bodies of children and average Americans. And if you took those results and then stratified them by race, Black people had higher levels of chemicals, including DDT, in their bodies than white people. We had this evidence starting in the ’70s, completely correlated with what we knew about where and how DDT had been used for decades. And we didn’t act on it.

I tell the story of Triana, a small African American town in northern Alabama. Its mayor, Clyde Foster—who was a scientist and mathematician at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)—became aware of high DDT levels in the fish in the river running through his community. He turned to the federal government for help investigating exactly how much DDT the town’s residents had been exposed to. The results of Foster’s actions was that the company that was responsible for manufacturing the DDT reached a $24 million settlement [to compensate the town’s residents], and the EPA agreed to make Triana a Superfund site, meaning the agency would oversee DDT’s cleanup.

In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) agreed to study how much DDT was in the bodies of the people living in that town and what it was doing to them. Triana’s story revealed that we had focused on the middle class food supply. In the town of Triana, people were eating fish right out of the river because it was free. People were consuming DDT at levels that scientists hadn’t even thought were possible.

Eventually, studies investigating people’s exposure to persistent and other chemicals through the diet started to take these variables into account. They began to ask: How we can fully account for the different diets that people living in the U.S. are consuming and what that might mean for their chemical exposure? As a result several studies looked at dietary patterns of Alaska Natives, including those who ate large amounts of marine animals with high retention of DDT in their fat. We began to see different patterns of exposure decades after people had been exposed.

Subsequent studies have shown that the children and grandchildren of people exposed to DDT suffer the impacts of this chemical, so $24 million isn’t actually a very large settlement.

Yes, and it’s just one chemical. As scientists started studying people in Triana, they found that people in town also have high levels of PCBs. These are industrial chemicals used in electronics and other products. So there was something there that nobody even knew to ask about. The legacy of environmental racism is so much bigger than we imagined.

Why did the tobacco industry want to “bring back” DDT after its ban?

In the beginning, the industry studied DDT because it was used in tobacco fields. In the early ‘60s, when the Surgeon General linked smoking to cancer, smokers actually wrote the tobacco companies saying, “maybe it’s the pesticide.” Then, as European countries proposed limits on the amount of DDT on imported crops [including tobacco] . . . the tobacco industry started pressuring growers and the USDA to stop using DDT. The USDA eventually moved to ban DDT on tobacco before the full national ban.

Fast-forward to the late 1990s, when the tobacco industry started fundraising for a campaign to bring back DDT. It was a communications campaign to convince the public that DDT should never have been banned in the first place because millions of people, particularly children, were dying around the world due to malaria and DDT was a tool to fight it. Big Tobacco didn’t actually care about DDT. The industry was trying to protect the [global] market for cigarettes by undermining public support for federal regulations and for the idea that western nations should be dictating global health policy. This wasn’t a simple story of the tobacco industry being the bad guy. Conservative think tanks had approached the industry with this idea because they wanted to promote a right-wing ideology and knew the tobacco industry would fund it.

Campaigns aimed at discrediting science seem to be a threat in many current scientific debates. How do we remain vigilant in the face of those campaigns?

When it comes to some of the scientific debates today, we might not even know who’s in the game, who is behind the scenes pulling levers and determining what we hear and what we don’t hear. One of the biggest takeaways from the book is that it’s crucial for us to know who we’re hearing from and why we’re hearing from them . . . to know what their real interests are and who is giving them the power and the voice that they have. And it’s not just about interests, but also about how those interests create allies out of different people. It isn’t always as simple as looking for industry sponsorship or ties. Rather, it’s a matter of understanding the ideological bent and objectives of the people who are sharing scientific stories.

DDT’s fall from grace is touted as a major success story by the environmental movement. But we’re still awash in toxic chemicals. What has the ban accomplished?

The ban distracted us from the fact that pesticide use was only increasing and has continued to increase. We banned persistent organic pollutants, including DDT and other organochlorine pesticides, but we replaced them with organophosphates [such as chlorpyrifos], which are actually more toxic, and we use them in greater amounts. We then started to ban some of those pesticides and have replaced them with neonicotinoid pesticides and so-called systemic pesticides. We’re just repeating everything all over again, using new chemicals without understanding the full scope of their impact or their long-term effects.

We’re not reducing our reliance on pesticides at all and we’re further and further diminishing the total insect population in the U.S. and the globe. We need insects for our survival, and we haven’t even begun to grapple with where we’re headed. This is the thing that scares me more than the toxicity of a chemical like DDT. It’s the bigger questions related to our utter dependence on and over-use of such a wide array of ever-changing and insufficiently studied chemicals that are indisputably reshaping the world we live in. Probably not for the better.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.