The pandemic has wreaked havoc in school districts nationwide. Could feeding all students free meals be the solution?

The pandemic has wreaked havoc in school districts nationwide. Could feeding all students free meals be the solution?

June 29, 2020

October 9, 2020 update: The USDA today announced that it would extend waivers for free school meals through the 2020-21 school year, allowing school districts to provide meals to any student for free, regardless of their ability to qualify for subsidized meal programs.

When Metro Nashville Public Schools (MNPS) served its last meals in cafeterias on March 11, the district was already reeling from violent tornadoes that had caused widespread destruction and killed 25 people a week earlier. Then, with COVID-19 infections rising, school nutrition director Spencer Taylor was tasked with figuring out how to keep feeding students—at home.

Taylor quickly set up three production facilities and 15 distribution sites linked to 40 bus routes. Soon, MNPS was distributing thousands of meals per day to children who needed them; at the program’s peak, it served between 9,000 and 10,000.

But that’s a far cry from the 82,000 meals the district serves daily during a normal school year. More than three months later, it’s averaging about 6,000, less than 10 percent of the meals served when schools were in session, and Taylor expects those numbers to drop even further over the summer. That means MNPS has lost 90 percent of its reimbursement income and has had to tap into its financial reserves to stay afloat.

With a few exceptions, the vast majority of districts—from Kentucky to Florida to Northern California—are in the same situation: Their fixed costs are remaining, or rising, and their incomes have been slashed. Now, they’re facing the uncertainty of the fall semester while managing massive financial shortfalls.

“You’re talking about programs that are completely built around how many meals were served and how much money we’re able to save,” he said. “COVID has wreaked havoc on our reserve balances, and we’re generating a fraction of the income . . . and we just don’t know if kids are going to come back.”

Like many other aspects of the food system impacted by the pandemic, school food advocates and experts say that the effects of the virus have laid bare the longstanding issues with public school meal programs—from a reimbursement rate that barely covers the cost of ingredients, to requiring students prove their low-income status in order to qualify for meals. And they’re using this moment to call for policy fixes that would help districts feed children through the crisis and beyond, from short-term waiver extensions to a renewed long-term rallying cry for universal school meals.

And while the numbers look dire for the districts he works with, Dan Giusti, a chef and founder of Brigaid, a for-profit school meal company based in New London, Connecticut, said more people are suddenly paying attention. “I’ve never heard so many conversations, in general and at a higher administrative level in school districts, about food service,” he said.

Unlike other departments that are allocated money through district budgets, school nutrition directors are typically tasked with running meal programs as self-sustaining businesses, and keeping the balance sheet in the black is a massive challenge. Many districts depend heavily on federal reimbursements for students that qualify for free and reduced-price meals. The reimbursement rate for each free lunch is about $3.50, which may barely cover the cost of ingredients, and handling reimbursements while meeting other federal standards like nutrition requirements requires time-consuming administrative work.

“For a lot of federal programs, they give you the money up front, but school meals aren’t like that,” explained Morgan McGhee, the director of school nutrition leadership at FoodCorps. “You have to serve the meals, do tons of paperwork, and then get reimbursed—and all of that on a timeline.”

“When schools closed, every school meal program off the bat lost all of their support funding. It was an immediate slash in revenue for schools across the board.”

Schools also make money by selling snacks, catering, and selling meals to students who don’t qualify for aid.

“This is where you run into the problem with COVID,” said Diane Pratt-Heavner, director of media relations for the School Nutrition Association (SNA). “When schools closed, every school meal program lost all of their support funding—all of the à la carte sales, any catering program that they had, and their paid meals. So, it was an immediate slash in revenue.”

Despite that loss, 95 percent of school nutrition professionals who responded to an SNA survey in early May reported mobilizing to feed emergency meals to students at home. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) waivers allowed them to continue to be reimbursed for meals distributed, but like MNPS, most distributed far fewer meals than normal, meaning reimbursement dollars dropped.

Meanwhile, many districts continued to pay staff members who weren’t working, and social distancing restrictions and the labor involved in packing meals made operations less efficient. “We’ve heard from our members that . . . the number of meals that they could prepare with their staff per hour went way down,” Pratt-Heavner said. Schools also had to buy personal protective equipment, sanitizing supplies, and packaging materials, as well as additional infrastructure such as refrigerated trucks.

Brigaid’s Giusti said food costs also increased for many districts due to the suspension of the “offer versus serve” provision. In school cafeterias, kids are only required to choose three out of five meal components. When packing meals to go home, however, districts had to provide all five in every meal.

“All of that added up very quickly,” said Katie Wilson, the executive director of the Urban School Food Alliance (USFA), which represents 12 of the largest districts in the country. Collectively, those districts estimated meal program losses of $38.9 million per week during the school year.

In the SNA survey, close to 70 percent of respondents anticipated financial losses due to COVID feeding programs, with a median loss of $200,000 per district. In larger districts, however, that loss was $2.4 million.

In 2019, according to the USDA, close to 22 million students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. Districts rushed to set up emergency feeding programs with the understanding that many children from low-income families already depend on those daily meals. But since the start of the pandemic, each week, more than a million Americans have filed for unemployment for the first time, and food banks around the country have faced unprecedented demand.

With the new school year right around the corner, school districts are grappling with how to stay solvent. “We know that millions more children are going to be eligible [for free or reduced school meals] and trying to make sure that all of those kids are enrolled in the program is going to be an enormous task,” said Pratt-Heavner.

Processing individual applications every year often involves hiring temporary staff and hustling to get applications in and approved before school starts. “Can you imagine . . . how many more families are going to be applying?” McGhee said. “How does that fall on the districts? Do they have the staffing? The administrative burden is a real thing.”

Some districts, like MNPS, are able to avoid this process by participating in the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), which allows districts to serve free meals to all students if at last 40 percent of the students are from low-income families. However, the USDA uses enrollment in programs like SNAP (not unemployment benefits) to determine eligibility for the program.

Taylor and others said there are likely going to be many families that would qualify for free or reduced-price lunches based on income, but have not applied for SNAP and therefore won’t be counted in the data yet. “There are going to be new people who are acutely affected who aren’t used to being in this situation and may be hesitant to apply for those services,” Taylor said.

And for districts that just meet the CEP criteria, making up the cost of providing free meals to the rest of the district is still a challenge, likely exacerbated in this moment by depleted cash reserves.

“You only get a percentage of that money back. It’s no charge to the child, but the district is responsible for some of that cost,” Wilson explained. In other words, while the program allows schools to serve free meals to all students, if just 40 percent of them meet the qualifications, it doesn’t completely cover the cost of providing meals to the remaining students. Instead, it uses a formula to determine how much the district receives in reimbursement. “In most cases, they have to have 65 percent [of students] qualifying to make it work financially,” Wilson said.

To address all these challenges, advocates have called on the USDA to allow emergency feeding programs to continue through the 2020-2021 school year. House Democrats also included a provision in the HEROES Act that would reimburse school food authorities for a portion of the operational costs of providing emergency meals during the pandemic, but the Senate has yet to take up the legislation.

“You’re asking our most vulnerable students to jump through hoops and prove that they’re hungry. And we know that they are.”

And yet, most advocates say these small fixes don’t do enough to get at the root of the problem—that figuring out which students qualify for free meals is going to be more complicated than ever, potentially adding to the financial devastation district meal programs face, increasing lunch shaming, and making it more difficult to feed students while maintaining minimal contact.

With the current system, they’re “asking our most vulnerable students to jump through hoops and prove that they’re hungry. And we know that they are,” said McGhee.

As a result, advocates are issuing a renewed call for universal school meals. On June 4, the SNA sent a letter to USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue asking the agency to “provide all students school meals at no charge to guarantee they are nourished and ready to learn.”

The USFA is in the process of launching a major campaign in support of the policy. “Everybody’s been pushing for universal free meals, and I think if we could just get it for the 2021 school year, it would first of all help the school districts financially, and it will help every family that’s in crisis,” said Wilson.

Just as the pandemic has illuminated risks faced by other vulnerable populations in the food system, such as meatpacking workers, and caused many to look toward larger systemic solutions, McGhee noted that the moment presents an opportunity to tackle inequalities that persist in school meal programs.

“A lot of districts are going to feel the effects for years to come,” she said. “This moment is exacerbating inequalities. The question is: How do we address them?”

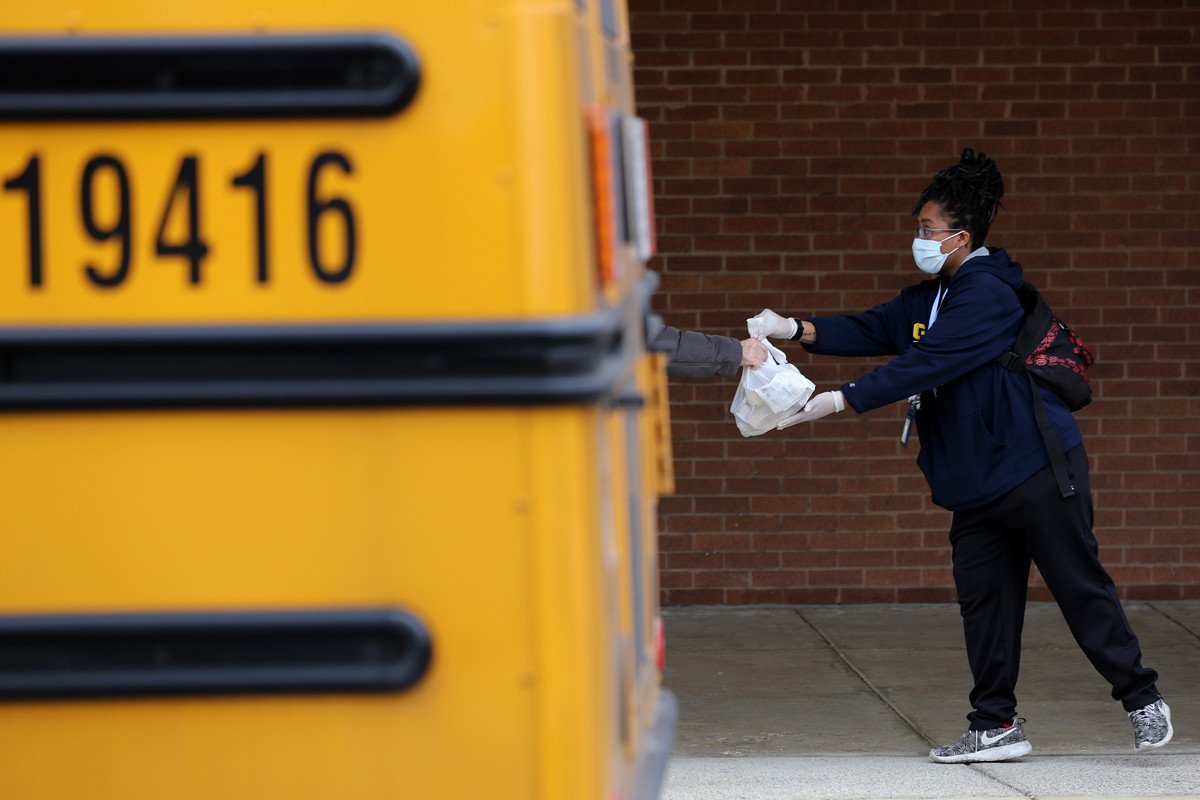

Top photo: A Montgomery County (Maryland) Public Schools worker helps distribute bags of donated food as part of a program to feed children while schools are closed due to the coronavirus. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

It appears by inference to the previously noted process steps above that feeding ALL children “Free Lunches” is a good objective, thus removing these current process costs. This would provide the means for all federal, state, county, and local agencies responsible for feeding our children to achieve the goal of feeding children more efficiently.

The net affect of well intentioned legislation, leading to government regulation, which leads to agency process controls, combined with time (years of policy growth), mixed with conflicting multiple agency internal policies and missions (aka. funding budget battles) has created a “Rube Goldberg” like children feeding solution. Its time to put all our combined meal production assets, kitchens and meal preparation staff, to work more efficiently and provide world class solutions to child hunger.