Pesticide labels are designed to help prevent dangerous exposure, but the EPA doesn’t ensure most farmworkers can read them—an oversight that has serious implications for their health, and the environment.

Pesticide labels are designed to help prevent dangerous exposure, but the EPA doesn’t ensure most farmworkers can read them—an oversight that has serious implications for their health, and the environment.

August 30, 2022

Photo CC-licensed by Seersa Abaza, IWMI.

Update: In December 2022, the Pesticide Registration Improvement Act of 2022, which included bilingual labeling requirements, was included in the larger the appropriations act and signed into law. On June 15, 2023 the EPA is hosting a webinar asking for input on how to make bilingual pesticide labeling accessible to farmworkers.

Pesticide labels are more like long technical manuals, sometimes totaling 30-plus pages. The intent of all that information is to minimize the risk of handling the highly toxic chemicals. And there are a lot of risks: Depending on the strength of the pesticide and exposure, farmworkers who come into contact with pesticides can land in a hospital with headaches, rashes, vomiting, and nausea, not to mention the potential for serious long-term health consequences like cancer.

While Spanish is the dominant language for 62 percent of farmworkers in the U.S., pesticide labels are typically only printed in English. “We’ve been fighting for bilingual pesticide labels for 15 or 20 years,” says Jeannie Economos, pesticide safety and environmental health project coordinator with the Farmworker Association of Florida. “It’s very frustrating.”

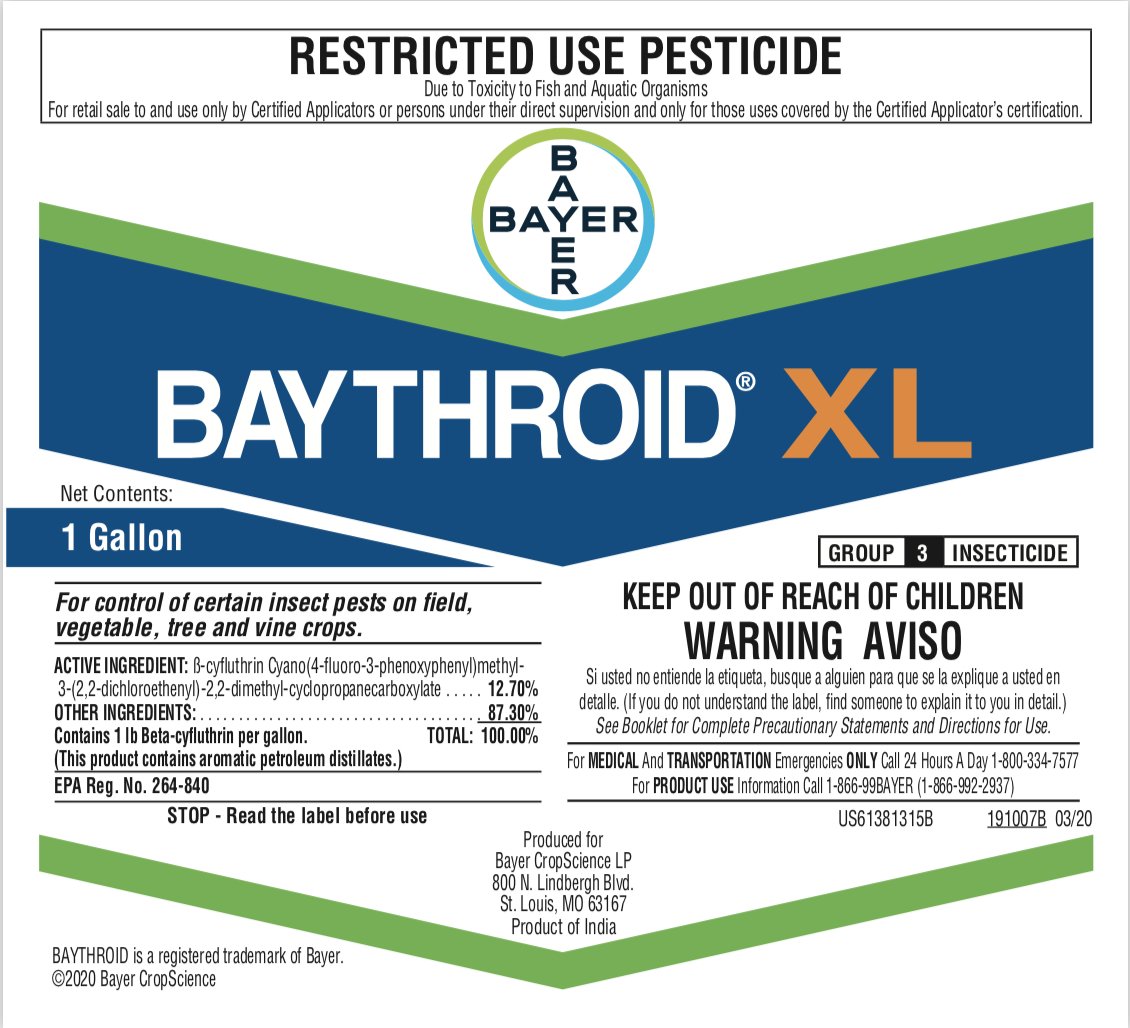

Some of the more powerful pesticides used in agriculture may come with one small message written in Spanish. Under the Spanish words advertencia or aviso, which mean “warning,” the labels typically include one sentence that reads: “If you do not understand the label, find someone to explain it to you in detail.”

Page 1 of the 40-page label for Baythroid, a widely used pyrethroid. Of the entire document, only the “Aviso” here and on page 40 provide any information for non-English readers.

But advocates say the chances that a worker will find someone to translate these labels before they apply the pesticides are low. And farmworkers are often under immense pressure to work quickly.

In the last few decades, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has taken steps to better protect farmworkers from pesticides, but Economos says when it comes to bilingual labeling, advocates have “gotten nowhere.”

Now, change may be on the horizon. A recent petition from the Center for Biological Diversity urging bilingual labels reignited the issue, although one of the primary arguments against bilingual labels has been the fact that printed labels are already too long. Technology, however, can address that. “Farmworkers may not have a decent place to live or transportation, but they have smart phones,” Economos says. “They could scan a QR code and see the important parts of the label in Spanish.”

This precaution could ensure Spanish-speaking workers have access to safety precautions, and information about what protective gear is best and what to do if something goes wrong. And while agricultural chemicals also come with safety data sheets, which are also sometimes translated into Spanish,

About a year ago, the Farmworker Association of Florida helped a woman who experienced a sudden blurring of vision and patchy, irritated skin after spraying a pesticide at her job in a central Florida nursery. A native Spanish-speaker, the woman couldn’t read the label to find out whether her symptoms aligned with those listed. She took a photo of the label, and with Economos’ help, confirmed her symptoms. A year later, her eyes still aren’t fully healed.

“Two-thirds of the people who are exposed to pesticides and suffering the health effects can’t understand the informational label so they can’t take the precautions they need to take.”

A recent study showed that people of color are more likely to suffer harm from pesticides than their white counterparts. According to the research, 90 percent of pesticide use in the U.S. comes from agriculture, endangering the majority-Latinx workforce. The study cites English labels as one reason for this disproportionate risk. While the “EPA approves pesticides assuming that all pesticide label directions can and will be followed,” the study reads, the agency doesn’t ensure the label is in a “language the user can understand.”

Though it’s difficult to link harmful pesticide exposure directly to a worker’s inability to read the label, research conducted in Washington state analyzed public health data between 2010 to 2017 and found that 79 percent of 630 farmworkers with pesticide-related illnesses drew a connection to either a lack of access to the chemical’s label or a lack of understanding of what it said.

“This is an environmental justice issue,” says Mayra Reiter, project director of occupational safety and health at Farmworker Justice. “Two-thirds of the people who are exposed to pesticides and suffering the health effects can’t understand the informational label so they can’t take the precautions they need to take.”

Advocates are urging the EPA to use its Label Improvement Program (LIP) to mandate bilingual labels. “We’re not asking them to do all the (pesticide) labels at the same time,” Reiter says. “We would eventually like all pesticides to have Spanish and English, but we’d like to prioritize the things that are most toxic.”

In theory, that’s what the LIP is for. Established in 1980, the program was created to require pesticide registrants to revise their labels to keep health and safety information as robust as possible. If the registrant didn’t comply within a specific time frame, its product could be withdrawn under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIRFA), the law that controls the approval, sale, and distribution of pesticides.

In 1984, LIP required several changes to 16 fumigant product labels, including a Spanish warning statement on the front panel and statements about flammability. J.W. Glass, an EPA policy specialist with the Center for Biological Diversity, says that initially the EPA proposed codifying LIP into its existing regulations, but by the late ‘80s, he says, “industry groups objected to the codification of the program,” and LIP’s potential power fizzled.

The program remains, but Glass says it’s rarely utilized and was last used in 1994 to amend labels for rat bait. The Center for Biological Diversity’s petition for bilingual labeling is also requesting the codification of LIP to lock in a more established, orderly process for label improvements that could better protect both people and endangered species.

Reiter says that starting around the late ‘90s, as Mexican and Central American immigrants began comprising the majority of the farmworker population, advocates realized that pesticide labeling had not caught up. “There has been 20 years of conversations around this,” she says.

In 2009, the Migrant Clinicians Network and other farmworker interest groups petitioned the EPA to require all pesticide labels be printed in both English and Spanish, and in 2011, the agency opened the proposal to public comment. Advocacy groups filed their support, as did the Arizona Department of Agriculture, the ambassador to Mexico, several doctors, and multiple public health agencies. Pesticide manufacturers and some agricultural trade groups resisted the change, citing extra cost and lengthy approval times for the updated labels at both the federal and state level.

Syngenta, a global pesticide giant, was an outlier. It supported the translation of key portions of the label, including personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements, first aid, precautionary statements, and other safety instructions. (Civil Eats contacted Syngenta and Bayer, another large pesticide manufacturer, for this story; neither company responded to questions.)

In the years that followed, the EPA took some steps to better protect farmworkers from dangerous chemicals. In 2015, the agency improved its Agricultural Worker Protection Standard (WPS), increasing the frequency of pesticide safety trainings for fieldworkers and pesticide handlers and mandating that they are offered in languages workers can understand, placing age limits on who could apply pesticides, as well as other measures, such as educating workers on ways to protect family members from pesticide residue.

Spanish-language labels for restricted-use pesticides are already available in Puerto Rico; in Canada, pesticide labels have required both French and English language for over a decade.

For instance, they recommended that workers leave their work boots outside their homes. (According to the study looking at pesticide harm in communities of color, agricultural operations are rarely monitored for WPS violations.)

In 2019, the EPA also released a Spanish Translation Guide for pesticide registrants that want to display labels in Spanish. Margaret Reeves, senior scientist at the Pesticide Action Network (PAN), says now that that guide is in place, requiring bilingual labels is the logical next move. “Spanish language labels [for restricted-use pesticides] are already available in Puerto Rico,” she says. In Canada, pesticide labels have required both French and English language for over a decade.

But in December 2020, in the final days of the Trump administration, the EPA decided not to propose a rule that would mandate bilingual labels.

The EPA leaves it up to pesticide manufacturers to decide if they want to provide a Spanish language label in addition to one in English. In an email, an agency spokesperson pointed out that for some highly toxic pesticides, including pyrethroids, the EPA requires a small portion of instructions in Spanish, including a warning not to pour products down the drain, keeping the chemicals out of water treatment facilities. The spokesperson also pointed to their updated Worker Protection Standard and Spanish Translation Guide as evidence of their efforts.

“EPA recognizes the need to provide agricultural workers and pesticide handlers, including Spanish-speaking individuals, with the information they need to protect their health and safety in a clear and understandable manner,” said the spokesperson.

For 10 years, Lisa Blecker worked as the pesticide safety educator with University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources (UCANR). She recently relocated to Colorado for a similar position, but during her time in California she says that while she saw pesticide safety training improve, she still sees labels as a critical, missing piece of the puzzle.

California’s trainings, she says, go beyond what is federally mandated. Pesticide handlers in California also must be trained on the specific pesticides they’re going to use. But, Blecker says, those trainings typically occur in one day, and may take place months before the pesticides are actually used.

“I guarantee that if you train someone on the safety elements of a label in February and you don’t apply it until May, they’re not going to remember everything,” she says. “What if they forget a specific glove type because there’s eight different types of chemical-resistant gloves? Sometimes the PPE is technical so it would be really great if someone had the opportunity to refer back to the label.”

“I guarantee that if you train someone on the safety elements of a label in February and you don’t apply it until May, they’re not going to remember everything. What if they forget a specific glove type because there’s eight different types of chemical-resistant gloves?”

Furthermore, according to the most recent National Agricultural Workers Survey, when roughly 2,170 farmworkers were asked whether, at any time in the prior year, their current employer provided them with training or instruction in the safe use of pesticides, about one-third said no.

Agricultural workers, like everyone who works near hazardous chemicals, should see what’s known as a safety data sheet on site that provides details about what chemicals are being used, the environmental and health hazards, and clean up instructions. Whether they arrive at 4 a.m. or in the middle of the night, they’ll find these sheets posted, typically at the edge of fields.

Blecker says those sheets do occasionally come in Spanish, but she estimates that “95 percent of the time” they’re printed in English. Furthermore, she says, the sheets are a requirement of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and are not as thorough as EPA-approved pesticide labels, which instruct workers how to prevent drift and keep chemicals out of water. Also, Blecker says, the PPE listed on the safety data sheets are recommendations intended to prevent illness or injury from exposure to chemicals in general. But labels outline specific PPE required for those applying or mixing pesticides, and her own research has shown that pesticide handlers in California who report illness often lacked the proper PPE. “If you’re going to translate [the data sheets],” she says, “translate the label.”

Reeves, with PAN, says Biden’s EPA seems open to either regulatory or legislative action requiring bilingual labels. “We are hopeful we will finally get movement on this,” she says, though she and other advocates know that, even if it happens, it won’t be a cure-all change.

For one, bilingual labels wouldn’t help the roughly 10 percent of farmworkers who are Indigenous and don’t speak or read Spanish fluently. And ultimately, Economos says, an environment free of toxic chemicals offers better protection than bilingual labels.

“Farmworkers are the most vulnerable and the most exposed, so they get top priority in my book,” she says. “The reality is we really need an alternative to pesticides.”

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

They will spray and we will eat and breathe the deadly poison.

The assumption here is that all farm workers are literate in Spanish.