Ana Rosa Villegas López points to the scattered images of her son on the walls of the Mecca Public Library in Southern California. In one, he stares straight at the camera, his sleeplessness etched into the dark circles under his eyes. The walls are covered with photos of children playing on a small square of artificial turf, dust-coated door mats, and the children’s inflamed, rashy arms, runny noses, inhalers, and humidifiers.

Building on findings from a recent study documenting the health impacts of poor air quality around the Salton Sea, California’s largest inland lake, López was one of 15 mothers who subsequently agreed to photograph their children and their environments. Three-quarters of the 36 caregivers in the study identified as Hispanic or Latino, and 24 percent identified as Purepecha, an Indigenous group from the Mexican state of Michoacan. Over half of them are farmworkers, as is common in the small, unincorporated communities that surround the sea.

On bad air quality days, López keeps her 8-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter inside to protect them from a cascade of symptoms that she says worsen with outdoor exposure, including congestion, skin allergies, and shallow, labored breathing that makes sleep elusive. A 2019 survey found that 22 percent of children have asthma in the region, almost three times the national rate of 8.3 percent.

“We watched as fish died by the millions and dozens of bird species disappeared. I always wondered, ‘What about us?’ We have been ignored.”

“The park in Salton City is covered in dust,” explains Nancy Del Castillo, one of the promotoras, or community health workers, who recruited caregivers to take pictures of their children. “It’s an undignified life,” she said at a recent event at the Mecca Library designed to share the findings to the community.

López’s family moved to Salton City from Arizona in 2018 when her then-husband got a job working in greenhouses in the Imperial Valley, south of the sea. Imperial Valley grows an estimated two-thirds of the country’s winter vegetables, as well as alfalfa for animal feed—but cattle has remained the No. 1 commodity for the last 64 years. Date palm plantations and orchards cover the eastern Coachella Valley to the north. Agricultural runoff from both valleys is the primary input into the Salton Sea, and with that runoff comes pesticides and nutrients such as phosphorous and nitrogen.

The Salton Sea is a complicated, dynamic ecosystem on the decline. At 240 feet below sea level, it has filled with water and dried many times over the centuries. In 1905, Colorado River floodwaters breached an irrigation canal and filled the depression with water. Since then, the sea has served as the dumping ground for decades of pollution from farming as well as legacy bomb-testing material.

In 2002, U.S. Geological Survey conducted sediment sampling from 73 locations and concluded that “the agricultural runoff that keeps the sea alive is loaded with salts, pesticides, selenium, and other metals.”

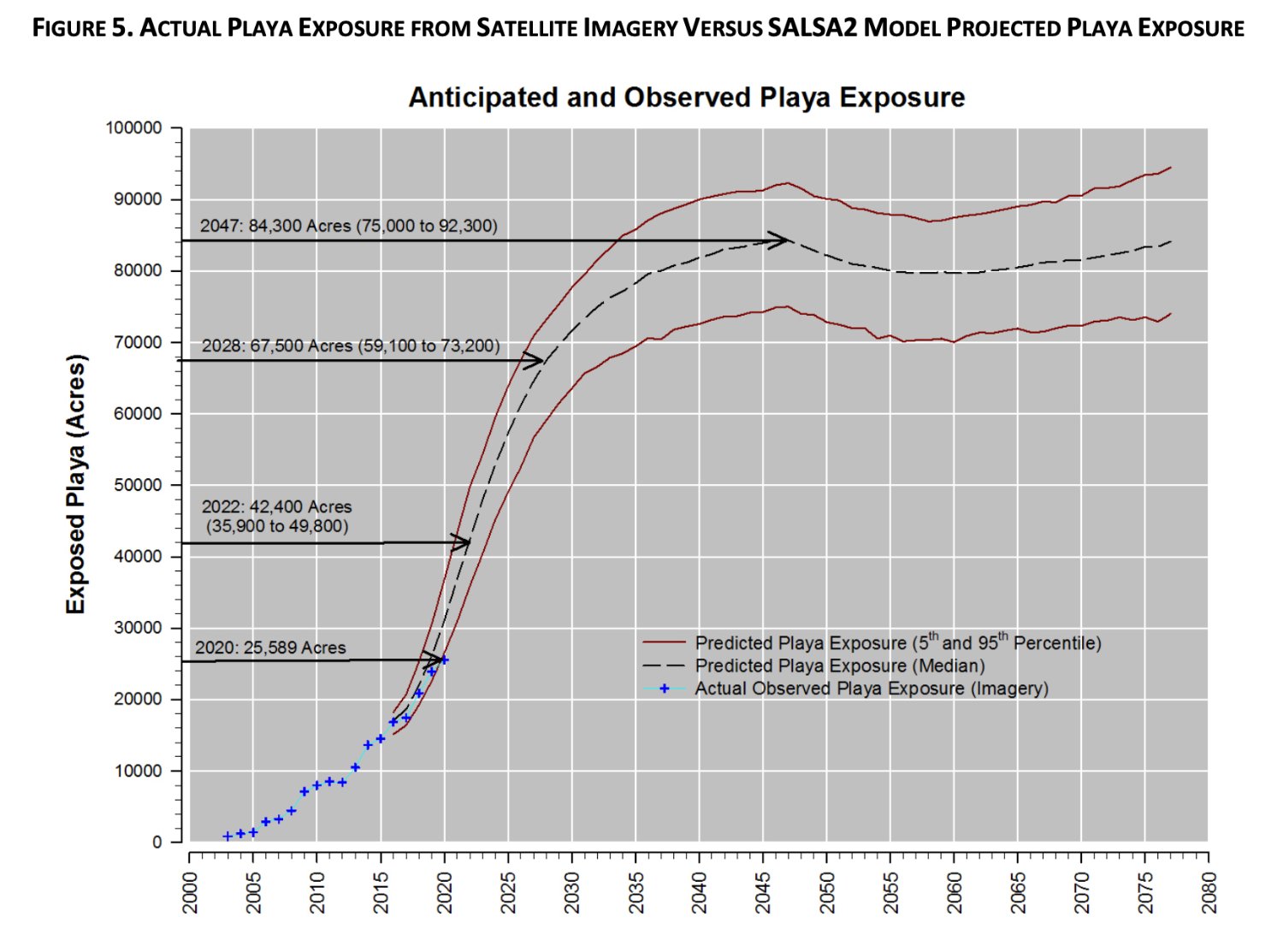

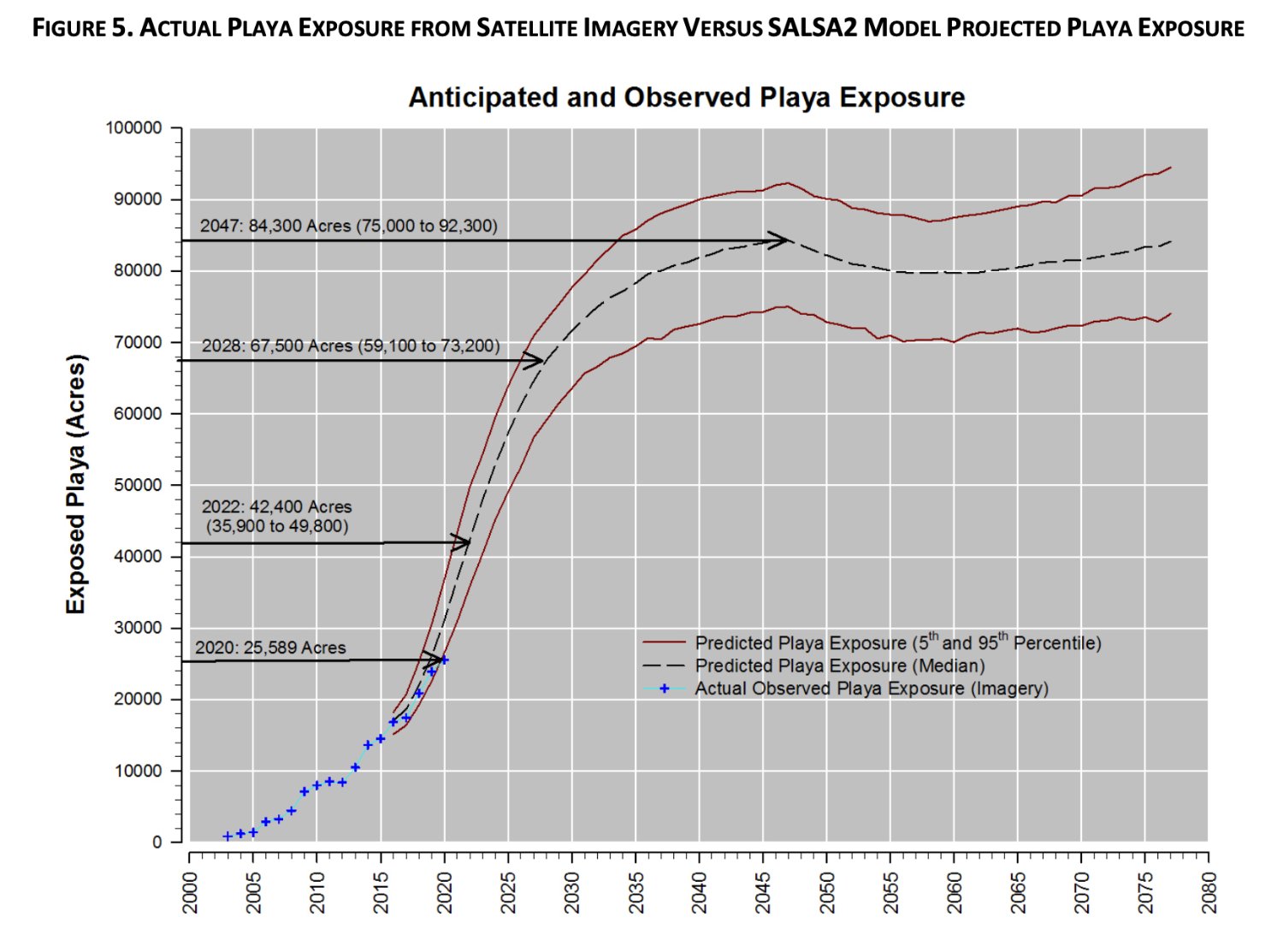

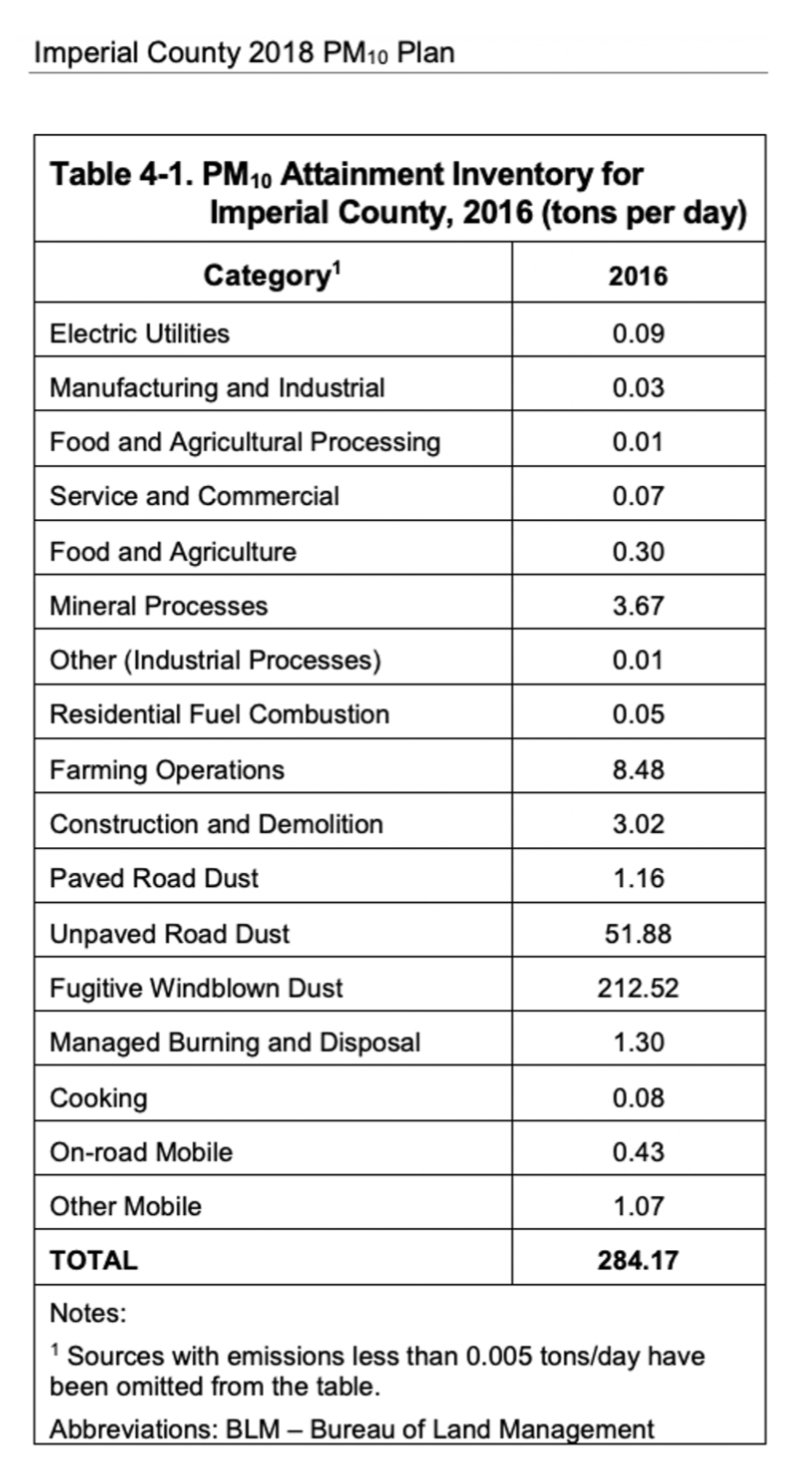

But a drought and reduced agricultural runoff have helped to shrink the shallow sea in the last two decades. Over that time, only a handful of smaller-scale research projects have attempted to document current sediment contaminants on what is now almost 20,000 acres of exposed playa that is adding dust to the region’s already poor air quality.

Chart source: The June 2022 Salton Sea Emissions Monitoring Program report by Formation Environmental for the Imperial Irrigation District.

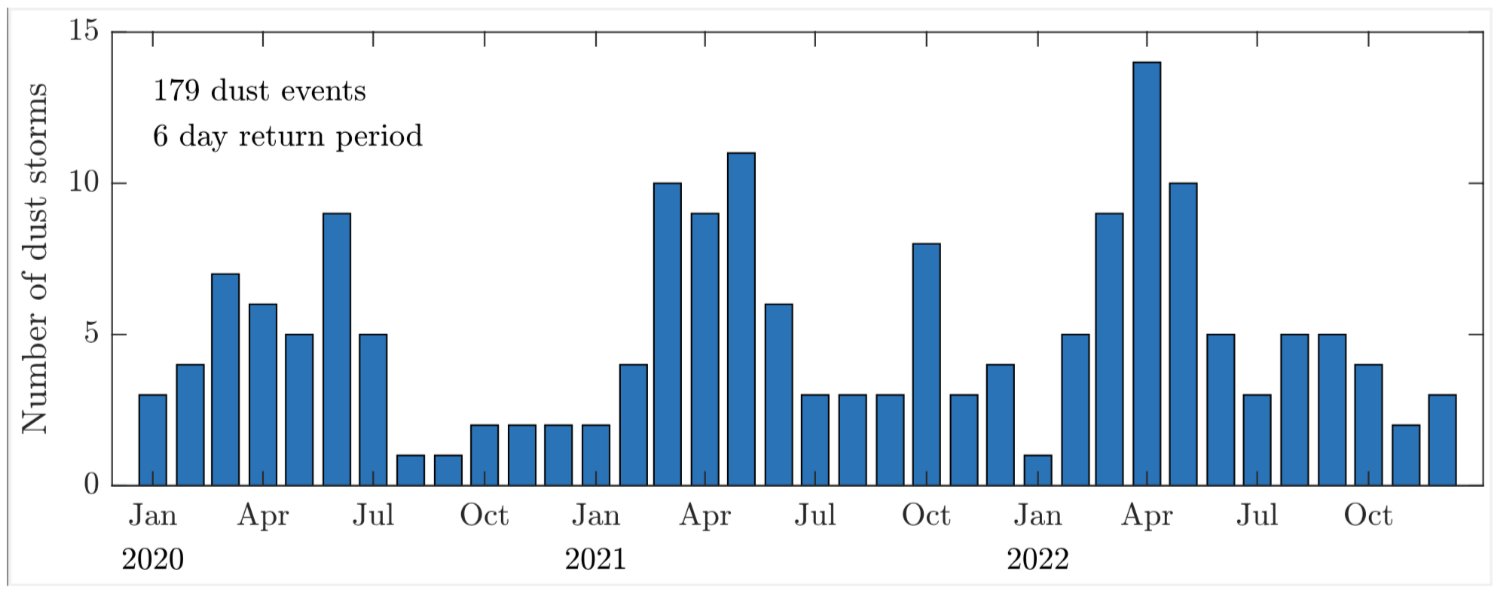

The air quality in the Salton Sea region is among the worst in the nation. Imperial Valley routinely gets a failing grade for particulate matter and ozone from the American Lung Association’s annual State of the Air report. Imperial Valley has already been out of compliance with national air quality standards since 2014—due to a host of factors, including the Salton Sea, industrial farming in a desert, a well-trafficked border crossing, and factory emissions from Mexicali.

Imperial County residents were exposed to over 1,200 pounds of pesticides—via the air, water, and on the plants themselves—per square mile from 2017-2019. That exposure rate is over 90 percent higher than the rest of California. On top of that, the region is the hottest in the state—with over 117 days over 100 degrees, according to a 2022 Hazardous Heat report.

Farmers around the Salton Sea have worked to use water more efficiently and reduce field burning. But they also use intensive, conventional practices that rely on chemical inputs. And there is little if any conversation about changing those practices for the good of the Salton Sea or the area’s residents.

In the last few years, the long-neglected region has been dubbed Lithium Valley as it has received unprecedented attention due to its precious lithium reserves needed to fuel the state’s clean energy economy. But residents, scientists, and public health advocates worry that this new gold rush will further an extractive dynamic without adequately addressing community health. And new science about the connection between water pollution and air quality suggests more investment is needed.

Health Impacts a Growing Cause for Concern

Like most of the roughly 100,000 residents who live within 10 miles of the sea, López describes the environment as “toxic.” Experts have identified layers of environmental insults in the region—including sulfuric odors, arsenic and selenium, dust storms, airborne pesticide residue, and smoke from agricultural burning—which are all possible contributors to the children’s chronic health conditions, including respiratory illnesses such as asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia, as well as chronic nosebleeds. Yet little research has focused on the cumulative public health impacts.

The shore of the Salton Sea. (Photo credit: Virginia Gewin)

Sandra Ramirez, a community advocate and former farmworker who picked grapes and lemons in Coachella Valley between 1995 and 2002, attended the presentation in Mecca. “We watched as fish died by the millions and dozens of bird species disappeared,” she said afterward. “I always wondered, ‘What about us?’ We have been ignored.”

Over the last 10 years, the state’s natural resource, water, and wildlife agencies crafted the Salton Sea Management Program (SSMP) to “improve air quality and provide critical environmental habitat.” But the effort is woefully behind schedule. The goal is to create wetland wildlife habitat and plant vegetation to suppress dust on 30,000 of the 60,000 acres expected to be exposed by 2028. As of March 2023, only 290 had been completed.

“The community’s public health issues have not been addressed, regardless of the amount of funding being allocated for the past two to three decades.”

The state of California has committed $583 million to the 10-year SSMP. But separate state funding designated to address the human impacts of air pollution in the region more directly is only a fraction of that number. Under Assembly Bill 617, the California Air Resources Board established the Community Air Protection Program to address and reduce air pollution health impacts in environmental justice communities. To date, however, only roughly $30 million of the total AB617 funding has gone to Imperial County, which currently has two of the state’s 19 designated communities—one was named earlier this year. And AB617’s ability to improve air quality has come under scrutiny.

Yet politicians claim that residents’ health concerns are front and center. “Lithium Valley will serve as a model for how we can protect our community’s health while we advance these [mining] objectives,” Representative Raul Ruiz (D-California) said at a March press conference.

Lillian Garcia, a Coachella Valley-based advocate with United for Justice Inc., bristles at that characterization. “The community’s public health issues have not been addressed, regardless of the amount of funding being allocated [to the wider region] for the past two to three decades,” she says. Since 2018, Garcia has been a consistent presence at public forums, requesting—unsuccessfully, so far—indoor air purifiers, public health research on exposure to contaminants, and improved medical access. Currently, there is only one clinic to serve communities nearest the northern shore of Salton Sea.

Many residents who do have access to transportation cross the border in search of prescriptions or medical care—which makes it difficult to track public health impacts. “Roughly one-third of our participant families seek medical attention in Mexico rather than locally,” says Ann Cheney, co-author of the Salton Sea children’s respiration study and a public health researcher at the University of California, Riverside.

Tracking Dust

Ruben Partida, a 41-year-old farmworker sprayed pesticides from a backpack in Imperial County for a decade. He says he routinely worked in unsafe conditions, without adequate protective equipment, and in extreme heat and poor air quality. In 2021, roughly 5 million and 3 million pounds of pesticides were applied in Imperial and Riverside counties, respectively, making them the 12th and 15th highest-pesticide application counties in California.

“We always work, whether there are dust storms or not,” says Partida, who stopped spraying when he was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2016, and is now working in irrigation. He added that the farm owners and contractors tend to view farmworkers, especially undocumented workers, as “disposable.” To protect workers from wildfire smoke, the state’s division of occupational safety and health (OSHA) implemented a Wildfire Standard that is triggered where the current Air Quality Index (AQI) for PM2.5 is 151 or greater. But, Partida and other farmworkers interviewed often work when the AQI around the Salton Sea is at 151 or higher without wildfires.

Partida says helicopters spray pesticides even when it is windy. As a result, the chemicals drift. Partida uses an inhaler and believes the air quality in the region has worsened over time—not just from dust storms and pesticides, but also due to particle emissions from farm animals and manure.

Like the story?

Join the conversation.