Emelyn Rude's new book, Tastes Like Chicken, provides insight into how the bird’s surprising past can inform the future of the industry.

Emelyn Rude's new book, Tastes Like Chicken, provides insight into how the bird’s surprising past can inform the future of the industry.

September 14, 2016

So far, Donald Trump has stayed mostly silent on food policy issues, but one of his forbearers, Herbert Hoover, was elected in 1928 after the Republican National Committee promised his presidency would lead to “a chicken in every pot.”

Today, that campaign promise would have to be very different, muses Emelyn Rude, the author of the recently published book Tastes Like Chicken: A History of America’s Favorite Bird. “I don’t know,” she says. “Maybe, ‘No more chicken every night’?”

The updated slogan Rude proposes is just one tiny example of the modern questions that arise out of the surprisingly riveting historical narrative of our clucking feathered friends. In the Depression era, and for most of American history prior to it, the birds were a scarce, expensive commodity that produced little meat in proportion to the labor required to grow and process them. Today, the modern chicken is a technological marvel that Rude calls “the most efficient meat-making machine on the planet.”

According to Tastes Like Chicken, Americans today eat 160 million servings of cheap, convenient chicken every day, and as of 2015, the global industry sold more than 59.2 million tons of chicken meat “conservatively worth hundreds of billions of dollars.” By 2023, in fact, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development predicts chicken will overtake pork as the world’s most consumed meat.

Of course, the many innovations that allowed for the mass production of affordable, packaged, boneless chicken breasts—from the first egg incubators to “Chicken of Tomorrow” breeding contests to the introduction of antibiotics in feed—also led to a system rife with serious social and environmental issues.

The industry has been associated with antibiotic resistance, low wages, and dangerous working conditions for poultry slaughterhouse workers, low wages and unfair practices for contract growers, endless animal welfare concerns, salmonella outbreaks, and environmental damage like runoff that contaminates waterways, killing fish and shellfish.

But is it possible to return to an era when only heritage chickens roamed? We asked Rude to share insights from her research to inform the coops of tomorrow.

You say in the introduction that you don’t even like to eat chicken. How did you end up writing an entire book about it?

Well, I’ve always loved food. In college, I took a class called “The History of the Human Diet,” and I went into this professor’s office, and he made this off-hand comment, “The chicken is an incredible piece of technology.” I thought that was such an interesting perspective. I looked into it, and it grew from there.

Writing the book didn’t change your taste at all?

I mean, fried chicken is tasty, but I think that’s more the fried attribute than the chicken. It made me more sympathetic to the chicken, this little bird that is actually amazing in and of itself. What we’ve been able to do with it, to transform it, it’s really incredible. I just have a bigger appreciation for the bird, I think.

Those technological transformations are a huge part of the book, and there are so many—from incubators to chicken genetics. Is there a single turning point when chicken went from being expensive and unavailable to the staple it is today?

I wouldn’t say there’s one single thing. If you ask the poultry scientists, they’d say the discovery of vitamin D. We couldn’t do any of the mass producing we do, all inside, all of this stuff, without that. There are so many other developments. The discovery that antibiotics are basically chicken Miracle-Gro, regardless of how you feel about that, made chicken cheap. The fact that you could add something to their feed and they grew three times as fast changed everything.

Of course that, like a lot of the other innovations, came with major consequences later on. Are there lessons from the history that can help us fix some of the issues with today’s chicken industry?

I definitely think there is a way that we can take into account all the factors—animal welfare, the environmental issues. Changes in the industry now are definitely moving towards organic, free range, etc. in reaction to consumer demand. But the consumer needs to know you can’t have five-cent chicken breasts anymore when the industry has to make those changes.

When commercial broilers came out in the ‘40s and ‘50s, people loved them because it was a completely new texture. It was like a pork chop—a juicy, fat food. It’s all about consumer preferences. You hear a lot about heritage breeds now. Some people say they have better flavor, but the non-commercial birds have a very different texture. You can’t get the huge, fat breasts most people love unless you raise the birds in a specific way.

The chicken industry developed the way it did because the only way the industry has been profitable has been by pumping out chickens in massive amounts. The farmers have to be taken into account, their livelihood. It’s very hard to make money raising chickens. It definitely has to be a balance.

What’s next for the chicken industry?

The thing I know for sure is that chicken as we grow it, our model, is definitely going to increase abroad. In the future, the whole world will become big chicken eaters [like] we are. Going through all the cookbooks, you go back 100 years and recipes used to be so diverse. Now it’s 60 percent cut chicken breasts—that’s the only thing people know how to cook anymore. It’s one of my weird fears, that it will take over the world, and there will be nothing left but boneless, skinless chicken breasts.

September 4, 2024

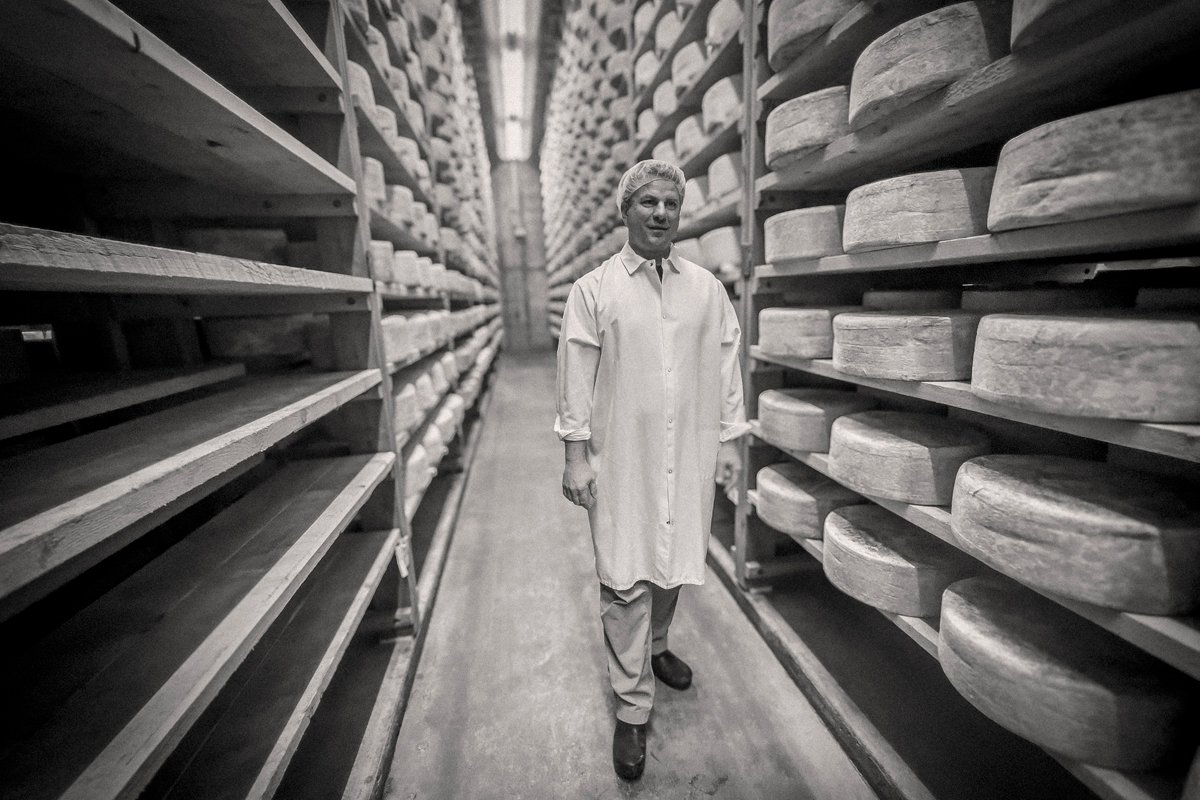

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.