Soil-health pioneers David Montgomery & Anne Biklé discuss the nutrient benefits of regenerative practices, and how they may also be a solution to drought in the West.

Soil-health pioneers David Montgomery & Anne Biklé discuss the nutrient benefits of regenerative practices, and how they may also be a solution to drought in the West.

December 1, 2022

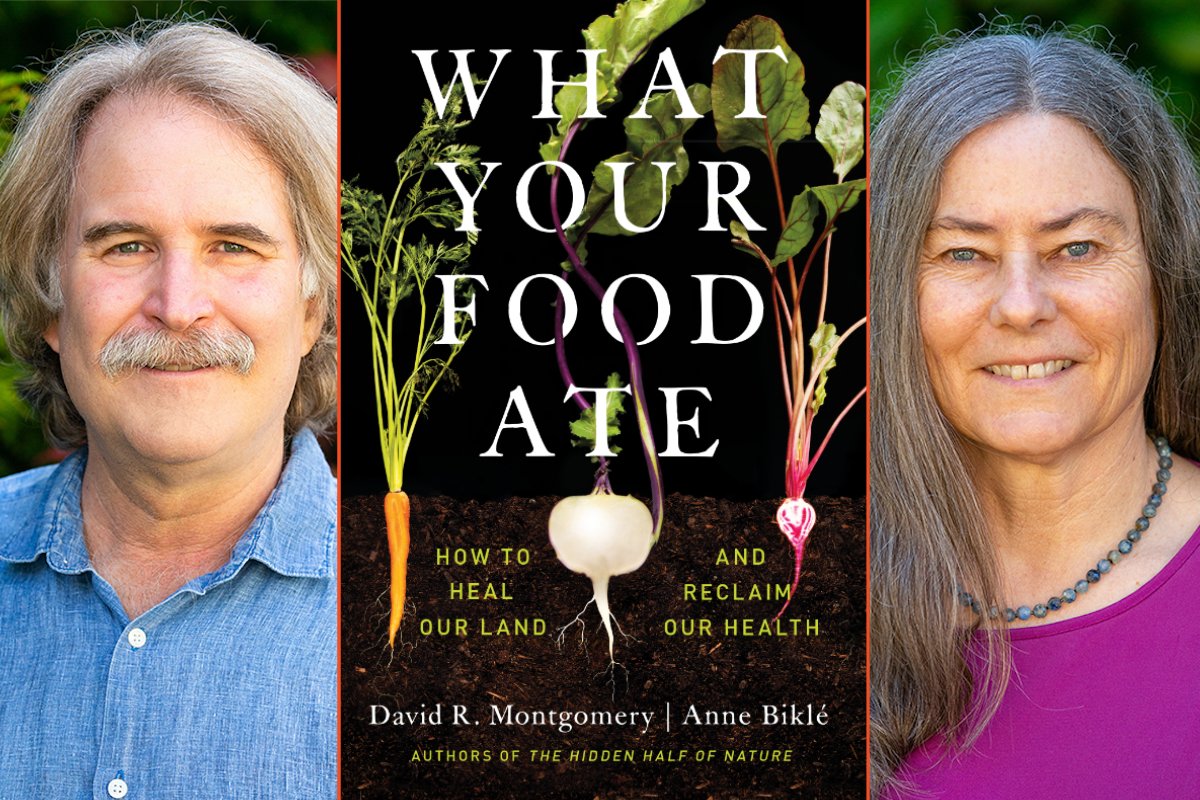

Author photos by Cooper Reid.

A version of this interview originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our award-winning newsletter for Civil Eats supporters. Become a member today and get the next issue in your inbox!

In their new book, What Your Food Ate: How to Restore Our Land and Reclaim Our Health, geologist David R. Montgomery and biologist Anne Biklé make a compelling argument that regenerative farming practices result in healthier soil and higher nutrient density in food.

In the book, the husband-and-wife team share the results of their own extensive research and the existing literature on soil health. Conventional farming practices, including tillage and commercial fertilizers, disrupt the necessary, healthy symbiosis between plants and the soil, they write, noting, “We traded away quality in pursuit of quantity as modernized farming chased higher yields, overlooking a farmer’s natural allies in the soil.”

We spoke with them recently about the nutrients that set food grown with regenerative practices apart, and why they believe those practices, including the no-till method’s greater capacity for holding water and preventing soil erosion, could be a key solution to drought in the West.

Fifteen years ago, when you wrote Dirt, there were very few people talking about soil health or about changing farming practices. How have things changed in that time?

David Montgomery: I’m impressed by how things have changed over the last 15 years. It has been very interesting to see the growing interest, not just among people who are interested in reforming the food system, but among farmers looking to farm better and to be more profitable. And there are all kinds of interests that have come together in the last 15 years that give me a lot of hope for continued momentum.

Anne Biklé: Farmers are definitely beginning to change their practices. Initially, a lot of the no-till movement was among conventional farmers. And I’m heartened to see that it has also crept out into the organic world. It’s really important that all farmers are seeing that the less we physically or chemically disrupt the soil, the better off the health of that soil is and then that can ripple out through their operations and pocketbooks. I hope that continues to catch on. I don’t think we’ve run into anybody who said, “I’m against soil health.”

Montgomery: There has been a lot of interest from farmers, consumers, and even companies, in terms of thinking about how they want to position themselves in the marketplace. We’ve spent a lot of time in the last 100 years worrying about growing enough food to feed everybody—and that’s a legitimate concern. But we took our eye off the ball collectively about the way that farming practices influenced the quality of food. It’s heartening to see a growing interest in that because I think we firmly believe we can harvest an abundance of very nutritious food to nourish the world. And if we can set our sights on that, as farmers, as consumers, as companies, and as governments, that can really help reform and change agriculture over the next few decades. Soil health is being talked about at COP 27, and there’s talk about support for regenerative agriculture in the farm bill. People are starting to pay attention.

“We’ve spent a lot of time in the last 100 years worrying about growing enough food to feed everybody. . . . But we took our eye off the ball collectively about the way that farming practices influenced the quality of food.”

You note that how we treat the soil affects how many important compounds are getting into our food supply. Can you say more about that?

Montgomery: We found that there are very clear effects on mineral micronutrients, phytochemicals, and the fat profile of meat and dairy, all of which have been connected to impacts on human health, not just in terms of how we survive, but whether we thrive. We can investigate the medical literature for what they do for us, but you have to look into the botanical and microbiology literature to understand why and how plants take up minerals in the first place. They’re not taking minerals from the soil so that we can be healthy; they’re doing it for their own purposes.

And the way that we farm influences how they’re able to do that. For example, getting atoms of the element zinc out of soil particles and into crops is mediated through partnerships with soil life. And the big player in those partnerships are mycorrhizal fungi, which facilitate the mineral uptake of crops. And there’s very clear literature that shows that plowing and the overuse of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers really impact how well plants are able to take up mineral micronutrients.

You ran an experiment where you looked at 10 regenerative farms that had converted worn-out soil over the course of a decade or two, and you paired those farms with adjacent conventional farms where regenerative practices had not been used over the same time period. In order to give us an idea of the difference in soil health, can you share the story of the wheat farmer who treated adjacent fields differently?

Montgomery: We had the opportunity to conduct two fairly limited but interesting and illustrative experiments. The first one was an informal experiment done by a wheat farmer in northern Oregon who was very interested in whether or not he could grow comparable wheat yields using cover crops and no-till instead of the glyphosate [the herbicide found in Roundup] fallow rotation typically used in his area. He was looking to see: Could he harvest about the same amount, or would the harvest go down?

He found that after two years, his yields were very comparable, and he offered us the opportunity to test the wheat. What we found is that most of the nutrients were higher in the more regeneratively grown crop. The biggest difference was zinc; it was more than 50 percent higher in the regeneratively grown crop. Zinc deficiency is a major micronutrient problem around the world, because we’ve bred modern varieties of wheat, to have high yields in nitrogen-rich environments, but that compromises their ability to partner with mycorrhizal fungi. So, they don’t take up as much zinc, and it doesn’t get into people who eat the wheat.

We hypothesized that the big difference we saw in this one example was due to changes in soil life, and we then went on to do a 10-farm comparison across the U.S. What we found was that, on average, the regenerative farms had about twice as much carbon in their topsoil, and their soil health scores were three times those of the conventional farms.

In terms of what was in their food, the biggest differences we saw were in phytochemicals and in certain vitamins. The phytochemicals were, on average, 20 to 25 percent higher, and certain vitamins were 14 to 35 percent higher on regenerative farms. In terms of minerals, it was all over the map given the geological variability of the continental U.S.

Biklé: One of the interesting things about this research—and something that I hope readers and eaters will think about more—is about things coming literally out of the soil. One of the chapters in the book is called “Rocks Become You,” because we’re trying to get the point across that rocks may be dead, but they are the source for all of these minerals: zinc, calcium, magnesium.

One part of the puzzle is plant health and plant nutrition. But it’s the biological interactions between a crop and its microbiome that is biologically mediated and the engine and the driver on the phytochemicals. And then we’ve got the soil health score, which is a reflection of biological activity. And that, in combination with purely sucking stuff up out of the soil, is the relationship between soil health, plant health, animal health, and human health. It’s all got to be intact and functioning.

I’d really like it if people thought about soil health and asked about its biological integrity, like: What level is that at? Is it low, and sort of limping along with crutches? Or have we got fully functioning robust relationships happening there?

What about the fact many of the current efforts to improve soil regeneratively in the West are being stymied by historic drought?

Biklé: A lot of soils in the West are not in good shape. There’s huge room for improvement there. Because when we start getting more life in the soil, more plants in the soil, you start to retain that No. 1 gold out in the West, which is water. The writing on the wall for drought in the West has been there for a long time. And now it’s really time to respond.

I think that if we can get agricultural regions and soils in better shape, then we’re going to be able to hang on to what water does fall. And that is going to be key—especially in California, the fruit and vegetable breadbasket of our country. And if we don’t get soil turned around in that state, it’s not going to be a good picture at all.

“When we start getting more life in the soil, more plants in the soil, you start to retain that number-one gold out in the West, which is water. . . . If we can get agricultural regions and soils in better shape, then we’re going to be able to hang on to what water does fall.”

Montgomery: The more soil organic matter you have, the higher the water-holding capacity of the soil. And the more water that falls as rain onto a field, it will sink into the ground where it could get to a plant root where a farmer wants it to end up rather than running off over the surface carrying away topsoil, fertilizer, and seeds.

That’s one of the real myths around tillage; a lot of people think that if you till the soil and you break it up, you’ll let more water sink into the ground, but the reality is that by pulverizing the soil surface, you basically create a crust. And then when that next drop of rain hits that crust, it runs off over the surface. The more life you have in the soil, the more [natural] holes that makes in the soil, and the more holes there are in the soil, the more water sinks into it.

If we want to make our farms more resilient to droughts, we would go whole hog into soil-building practices that enable the land to absorb and hold more of whatever water it gets, because the farmer can’t change the rain, but they can change their soil.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.