Marcus Weaver-Hightower explains in his new book how understanding political motivations can lead to better school meal policies, and why pizza is considered a vegetable.

Marcus Weaver-Hightower explains in his new book how understanding political motivations can lead to better school meal policies, and why pizza is considered a vegetable.

September 26, 2022

An excerpt of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only email newsletter. Become a member today to get the next issue in your inbox.

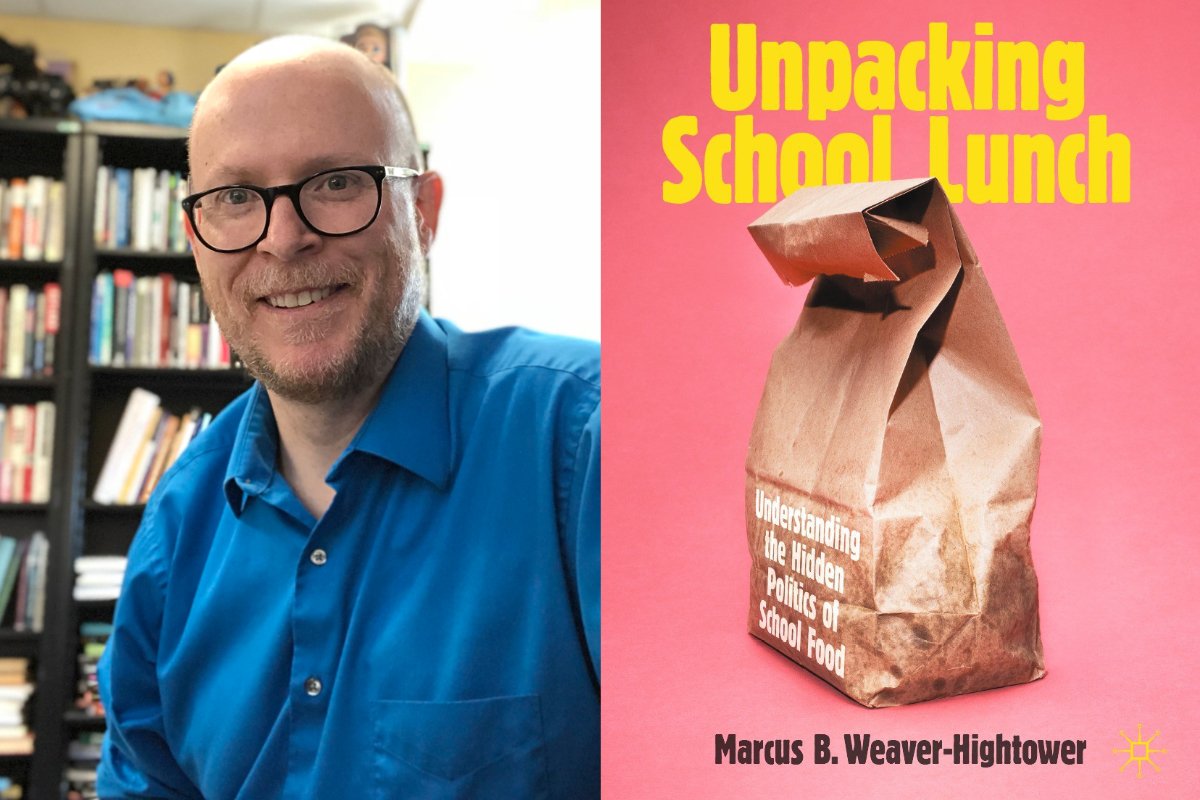

In his new book, Unpacking School Lunch: Understanding the Hidden Politics of School Food, Marcus Weaver-Hightower explores how the politics of school food shape the reality on the ground—from the kinds of meals served to children to where they’re prepared, and how much they cost. Weaver-Hightower, a professor of education at Virginia Tech, has spent the last 15 years researching school food politics and policies in the U.S., England, Australia, and beyond.

As a self-identified progressive, Weaver-Hightower makes a focused effort to describe in detail the various efforts taken up by conservatives to block improvements to school food, and details how addressing those efforts could lead toward a truly progressive vision for healthy school meals for all.

Civil Eats recently spoke with Weaver-Hightower about what the new school year has brought for school meals, pizza as a vegetable, and how more of us can advocate for better school food.

Can you tell us about the genesis of the book? It sounds like you’ve been working on it for a very long time.

I’ve always thought a lot about food; I was born into a family that had lots of farming in their background, so food was important and cooking was always a ritual. And then school food was anxiety-producing, because there were all those social distinctions that happened in the cafeteria. And I always felt like I was not amongst the “elite eaters,” if you will. My parents didn’t pack me lunch, and if they did, I didn’t have the “right kind” of peanut butter and stuff like that. So, I was always aware of it in my own life.

When I went back for my Ph.D. in education, I studied social inequality. And it occurred to me that so much of my experience in school was related to food—those were some of the best memories, but also some of the worst. So, while I did my dissertation work on boys’ education issues—masculinity, politics, and schools—school food was always on my mind, and I really started down the track in 2007.

Your children started going to school while you were researching this book. How did that change your interest in and understanding of the issues?

In the first chapter of the book, I talk about my son [who was born in 2007] going to school, and that was a great entrée for me into how those politics work on an individual basis. Before that, I was really focused on cafeterias and public policymakers, but when it gets down to the level of actual kids going to actual schools, it becomes much more complicated.

“It’s a fine line to walk between having a deep respect for the possibilities [of school meals], but also understanding that there are some deeply troubling aspects, too. How do we advocate for something that has so many problems?”

I have two kids, and one or the other is always in the hate portion of their love-hate relationship with school food. So, it becomes ethically complex for me to look at them and say, “I really deeply believe in school food and the possibilities that it has for social good and educational good,” and then have them come home and say, “Lunch was super gross today, can I please pack my lunch tomorrow?”

In some ways, seeing my kids go through school, it makes me a little bit more understanding of people who do have real, serious problems with quality and presentation and the environment in which kids are eating. It’s a fine line to walk between having a deep respect for the possibilities, but also an understanding that there are some deeply troubling aspects, too. How do we advocate for something that has so many problems, but also offers such possibility?

Your book is narrowly focused on the politics of school food and how those politics inform or explain the policies that school foods operate under, rather than also exploring nutrition, or health, or environment. What are the benefits of that approach?

There are a couple of different benefits. One is, I have a vested interest in thinking about educational politics writ large. And because I’m an education professor I can’t talk as well to many of those kinds of issues. But I can see the ways in which there’s an almost seamless throughline from school food, to school politics, to broader politics.

Most people think that government can’t do anything right—because it’s government food, and they’re making these decisions for us. But it’s only a small slice of government that is saying, “We need to spend as little as possible, only give these meals to kids who absolutely can’t afford it otherwise, and get by on the bare minimums of nutrition.”

“It’s important for folks who are interested in making the system better to understand these politics so they can participate in them, write their congressman, vote, or however they want to make a difference.”

That same small group [of conservatives] also fights really hard to make sure that the definitions we have of food, or water, or vegetables come to mean something in industries’ interest much more so than in kids’ interest.

It’s important for folks who are interested in making the system better to understand these politics so they can participate in them, write their congressman, vote, or however they want to make a difference. There are lots of progressive examples one can look to for inspiration; I include a few of those at the end of the book. For me, the main thing is using this lens as a springboard toward understanding how these policies come to be.

In the book you discuss the idea of ketchup as a vegetable, and pizza as a vegetable, but can you spell that out a bit more?

There are a number of them; for instance, water is something that was fought over for a while. The Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act (HHFKA) [passed in 2010] required water to be available for kids, and then people fought over well, what does that mean? Does it have to be just water coming out of the tap? Or can it be those, like, water-based beverages that have extra electrolytes and stuff—what counts as water?

When the Department of Agriculture was making the rules to implement the HHFKA, one of the things that they wanted to say was that two tablespoons of pizza sauce would no longer count as a vegetable serving. What followed was this legalistic word-gamesmanship, as well as industry lobbying, in order to allow pizza sauce to be considered a vegetable. In the end, the lobbyists got their way.

The result was great for the [companies] putting pizzas into schools, because it is a staple of the menu. And because it would cause a lot of disruptions for cafeterias, you saw groups like the School Nutrition Association coming out against the pizza as a vegetable change, because it would disrupt the normal pattern of school feeding, which includes pizzas, enhanced corndogs, reformulated French fries, and other foods that don’t doesn’t necessarily fit our colloquial definition, or the dictionary definition even, of what we would call food. It gets loosened up to suit the manufacturers, instead.

We often hear from school food advocates that small changes are better than nothing. But then over the last two and a half years we’ve seen a sea change in attitudes and practice toward universal free meals during the pandemic. What do you think about the results of an incremental approach?

In some ways, the structure of how we reauthorize school food every five years, rather than write a new bill each time, helps that process along. I understand the amount of time and effort it would take to fundamentally rethink policies, but at the same time, when you have gigantic health problems that are caused in large part by our food habits, something has to be done.

There are a couple of things that I think are good about incrementalist change; partly because the scale of school food is so massive—billions of dollars and millions of workers and a supply chain that we’ve all come to know is very complicated. So, those incremental changes help school food providers be able to cope with making changes to the program; it would be really disruptive for them to have to do a 180.

“Incrementalism has us stuck in a cycle of technical changes. The HHFKA was in a lot of ways revolutionary, but some of the ways that it made changes were susceptible to conservative backsliding.”

England [underwent] a pretty big sea change, with lots of rule changes, after Jamie Oliver did his school dinners series in 2005. It made a huge difference, but it was really disruptive for a lot of nutritional staff. They weren’t getting enough training or enough staff to be able to making these from-scratch dinners. And they were also in this precarious situation because Jamie Oliver had so convinced people that school food was terrible, so there was also this sudden decrease in people wanting to eat it.

Those kinds of moments can be very difficult to manage. At the same time though, incrementalism has us stuck in a cycle of technical changes. The HHFKA was in a lot of ways revolutionary, but some of the ways that it made changes were susceptible to conservative backsliding. As soon as Trump came into office, he was out to get the changes [that had been made] to school food. Part of that was the personal antipathy that many conservatives have toward Michelle Obama, and she had become the face of those changes. And because some of those changes were so incremental, the nutrition specialists and the people working in cafeterias, who needed them to be incremental, also said, “You know, we can’t really make these changes. And they were able to get their congressmen, people at the USDA, and people at the School Nutrition Association to push back because even the incremental changes are hard.

I personally think if you just rip the band-aid off and deal with the consequences, then folks will adapt eventually. And that’s exactly what has happened with the HHFKA; cafeterias have been adapting, and they’ve been meeting standards. It hasn’t happened quickly, but it has come to pass that school meals are much more healthy than they were before.

Was the pandemic that kind of rip-the-band-aid off approach?

I just wrote a piece that was published in the History News Network that covers that exactly: We missed a huge opportunity to renew school meals as free.

When big changes had to be made, we didn’t have time to think about the nuances, but we found our way toward getting meals out to kids for free. We were able to pay for it—we spent a little more than we might normally have, sure, but there are just so many more reasons to keep it going. If there is any silver lining to the pandemic, it’s that. We uncovered so many problems in our social safety net that people didn’t realize were in such bad shape.

“When big changes had to be made, we didn’t have time to think about the nuances, but we found our way toward getting meals out to kids for free.”

We have had two “blissful” years of not having to think about lunch shaming, paperwork, and schools and districts struggling with debt. And now a lot of that reprieve is gone, partly because of long-standing conservative antipathy to school lunches as only a form of welfare.

During this latest attempt to reauthorize universal free lunches, the House approved a bill that would have eliminated reduced-price meals [and provided more students with free meals instead], but [Kentucky Republican Senator] Rand Paul threatened to filibuster the bill unless the reduced-price meal was reinstated.

You’ve said a little about the changes Jamie Oliver prompted in England. What else did you learn about how England has managed their school food programs?

They have tracked, for many years, the same kind of politics over food that we have here. When Reagan was trying to dismantle school food in the U.S. in the ‘80s, Margaret Thatcher was doing the same exact thing in England, and actually succeeded. So England almost gives us a chance to see what would have happened here? But their turning it around is, I think, a really good model of how to take a gigantic food system and make some really drastic changes to it.

I visited a couple of different cafeterias in England, and they didn’t have freezers. They had one little one, like you’d have in your home, but everything else got prepared fresh. It did cause some difficulties for them, as I said earlier, but they were able to adapt and figure out how to do it better. But the warning is that even really good reforms don’t always last, especially if, as in their case, conservative politicians decide that they don’t want to pay for these programs, or if they have an antipathy toward or an ideological problem with spending tax resources on food. They can quite quickly roll back big changes. So that’s something that we need to be concerned about [in the U.S.].

What do you hope readers will take away from reading this book?

I hope they get an appreciation for the ways in which you can speak to people on their own political or ideological level. The middle of the book is focused on detailing the conservative positions and arguments around school food. I [hope readers] develop new ways of addressing their concerns, and countering misinformation. For instance, I think about how to reframe school lunches as not just about welfare, but there are many big, complicated questions that need to be answered.

I want readers to ask: what is it we actually want? Because it can’t be that we want 200 grams less sodium. I’m hoping to encourage people to think bigger and to think more disruptively, and less incrementally about what progressive school food means.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.