An inside look at young producers who are starting businesses, exploring alternative models, and feeding their communities in the face of ongoing meat market consolidation.

An inside look at young producers who are starting businesses, exploring alternative models, and feeding their communities in the face of ongoing meat market consolidation.

October 25, 2023

“During the pandemic we noticed a massive uptick in demand and that definitely has continued to some extent,” said Kira Jarosz, co-owner of Black Dog Farm in Livingston, Montana. Local chicken options are few and far between in the state. With low supply and high demand, Jarosz consistently sells out of pasture-raised and farm-slaughtered chickens each week. (Photo credit: Anthony Pavkovich)

For Black Dog Farm in Livingston, Montana, the early COVID lockdowns were a boon for business.

“It’s undeniable that the pandemic had a huge positive effect on our business,” said co-owner Kira Jarosz. “We’re out of chicken every week.”

Over the last three years, Jarosz and her husband Tim Anthony have seen a massive uptick in demand for their locally raised chicken and pork. Last year, they ran out of retail chicken by December and had a gap of six months before their first slaughter date in June.

“I think the increased interest had already started, but the pandemic put fuel on the fire,” said Matt Skoglund, owner of North Bridger Bison in Wilsall, Montana. Skoglund harvested nearly a bison a week out in his pastures last year to meet consumer demand. (Photo credit: Anthony Pavkovich)

Despite the state’s $4 billion-plus agricultural economy, only 3 percent of the food Montanans eat is produced there, down from 70 percent in the 1950s, according to a 2022 report from Highland Economics. Operating within an increasingly consolidated and globalized market, most of Montana’s commodity crops—beef, wheat, barley, safflower, lentils, and chickpeas—get exported out of state.

Producers like Jarosz are working hard to change this figure by raising, slaughtering, and marketing their own meat. At the same time, they are bringing transparency to how meat is raised and brought to dinner tables throughout Montana.

“There are not many people, particularly around here, that are raising thousands of chickens,” Jarosz said. “There aren’t replicable systems for doing this.”

“When the pandemic first hit, we had a huge influx in demand,” said Jaimie Stoltzfus, owner of Cowgirl Meat Co. in McLeod, Montana. “At the same time, we hit a wall with processing.” Despite the increased demand for local food and transparency in the food system, Montana’s infrastructure limits when and where producers can harvest their animals. (Photo credit: Anthony Pavkovich)

Instead of selling to a big meat packer or corporate distributor, Black Dog Farm sells directly to consumers at farmers’ markets and several retailers, wholesale to restaurants, and through a community-supported agriculture (CSA) subscription program.

To meet the demand for local chicken, Black Dog Farm owners Kira Jarosz and Tim Anthony built their own processing facility that allows them to butcher up to 20,000 of their own birds a year.

With funding from the CARES Act administered through the Montana Department of Agriculture’s Montana Meat Processing Infrastructure grant, they are now able to process all their birds on site for local sale.

Lack of market competition in the meatpacking industry has driven the percentage that ranchers receive for every consumer dollar spent on beef in the grocery store down to 40.5 cents, according to federal data.

Four conglomerates control nearly all of the market for meat products across the United States: Cargill, Tyson Foods, JBS, and National Beef Packing. The meat processing industry has experienced significant consolidation over the last 50 years as these large conglomerates absorbed more and more small processors. In 1977, the largest four beef packing firms controlled approximately 25 percent of the market. Today, it’s around 82 percent.

While Montanans have enjoyed relatively low food prices, the consolidation of production has led to less food processing capacity in Montana; more reliance on processing outside of the state and distribution infrastructure; and a smaller portion of retail spending on food going back to the farmer or rancher.

In response, a growing number of producers in Montana are distributing their own meat. “We’ve got more local or regional processing happening so that it’s easier to get the meat into people’s hands nearby,” said Robin Kelson, the executive director of Alternative Energy Resource Organization, a nonprofit that works on sustainability and strengthening food systems in Montana. “It keeps money local, and it keeps jobs local.”

Left: Instead of trucking his bison to slaughter, Matt Skoglund drives out into the pasture and loads his rifle. Waiting for the herd to relax, he looks for the animal he’s going to harvest by reading ear tags with the animal’s age class and observing individual animals for size.

Right:”It’s definitely a bag of mixed emotions when I take animals to town,” said Jaimie Stoltzfus. “It’s never easy to drop them off knowing that I care about the animals, and they’re going to be harvested.” Stoltzfus and her family work with Pioneer Meats, 25 miles away in Big Timber, to process their beef for their own retail label that they sell to restaurants, grocery stores, and directly to consumers in their surrounding community.

However, even with more local processing options, most of the meat Montanans consume is imported to the state after being processed elsewhere, according to Highland Economics.

Montana is known for ranching. There are 2.5 million head of cattle in the state and just over 1 million people, or roughly 2.5 cattle for every person.

Jaimie Stolzfus and her husband Austin manage the P Bar Ranch in McLeod, beneath the towering Absaroka Range, a subrange of the Rocky Mountains. Instead of selling their beef through the conventional market, they started Cowgirl Meat Co. to sell directly to consumers, retailers, and restaurants to capture more of each retail dollar.

“When the pandemic hit, we had the animals outside our door [ready to slaughter], but it’s not easy calling up the processor to get some meat harvested this week or next week,” Stolzfus said. “I wasn’t the only one trying to get meat processed.”

Matt Skoglund harvested around 50 bison in 2022. Once he’s field-dressed the animal and it arrives at his processor, Amsterdam Meat Shop, Skoglund said he’s filled with contentment and satisfaction because he believes so strongly in his process. He’s proud he can give his animals a full life and a low-stress death.

The rancher takes her animals a short 25 miles to Pioneer Meats in Big Timber, where her beef is slaughtered and packaged under her own label. While she appreciates having this local option, the processor is running at nearly full capacity and squeezing in an extra animal when sales are good isn’t a guaranteed option. “We have to plan a year out,” she said.

Stolzfus said there aren’t enough processing facilities in Montana for the current demand from producers.

Not all ranchers in the state can process their meat nearby. During the early days of the pandemic, many were plagued with long wait times for processing, closed processors, and long drives to open facilities.

Left: Despite having a processor that she enjoys working with nearby, Jaimie Stoltzfus said that she has to plan a year out for harvest dates. This bottleneck in processing requires her to estimate how much meat she’ll need for the year and leads her to store meat in her company’s freezer in case she has an uptick in orders. This inflexibility is a constant source of anxiety because she can’t make quick adjustments to inventory.

Right: The butchering team with Warrior Meats can hang up to eight cows in the cooler section of its semi-trailer. Once the meat is transported back to its grocery store in Ashland, Montana, the meat will be aged, cut, packaged, and returned to the rancher. Adam Zimmer is excited to ultimately build a whole new facility that isn’t physically connected to the grocery store, which will provide more jobs on the reservation and let the staff process more animals for the community.

As a way to confront this challenge, Warrior Meat Company on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation bought a mobile meat processing trailer that can be towed from ranch to ranch on the reservation.

As part of the nonprofit Peoples Partners for Community Development (PPCD), Warrior Meat Company is providing processing to build food security for tribal members and the broader community. Associated with the recently opened Warrior Grocery in Ashland, the butchers from Warrior Meat Company process four to five animals a month for local ranchers and cut nonlocal beef for their fresh case at the grocery store.

“Ultimately, our goal is to build a whole facility that isn’t part of the grocery store and become USDA-certified,” said Adam Zimmer, PPCD’s business development specialist. “We want to provide more jobs and handle more animals.”

Left: “How many chickens can we reasonably process with our hands?” Kira Jarosz asked. To increase the amount of chicken they’re able to provide, Black Dog Farm would have to build a bigger facility and hire more staff. It’s an investment Jarosz and her husband Tim Anthony are unsure they can, or are willing to, make.

Right: “The nature of not having enough processing facilities for the demand in Montana is still an issue,” Jaimie Stoltzfus said. Though more ranchers are looking for options to harvest and sell their meat locally, less than 5 percent of cattle born in Montana are processed in the state.

USDA inspection would allow Warrior Meat Company to sell local beef in the retail case at the grocery store, guarantee an outlet for local ranchers, and keep more retail dollars circulating on the reservation.

At the base of the Bridger Mountains, north of Bozeman, in a wide expanse of grass and sagebrush, Matt Skoglund and his family raise a herd of bison for their meat business North Bridger Bison. Wanting to provide the lowest stress option to his animals, he has chosen to field-harvest his bison with a rifle out in the pasture. This way, his animals spend their entire lives on pasture and surrounded by the herd.

Left: “It’s such a rewarding feeling to personally deliver meat that we raised,” Jaimie Stoltzfus said. Besides selling online to individual customers, she sells ground beef to Town and Country, a grocery store in Livingston, Montana, for resale in their freezer section.

Center: Sixty percent of the meat Matt Skoglund has processed stays locally in his community. Due to Skoglund’s field harvesting process, he is only allowed to sell directly to his customers and not through retail outlets like grocery stores or to restaurants.

Right: “Jaimie’s beef flies off our shelf,” said Richard Good, who works behind the meat counter at Town and Country, a grocery store in Livingston, Montana. He’s seen a growing demand from customers for locally sourced meat.

“I experience a range of emotions leading up to the shot,” Skoglund said. “I have a lot of adrenaline and nervous energy, which I consider a good thing.”

“Every day I’m just so grateful for the people that show up at the markets or place online orders,” said Kira Jarosz. “We feel so supported.” Jarosz looks forward to continuing to grow her business and provide more meat to her community.

Out in the field, he kills, cleans, documents with photos, and loads each bison onto his flatbed truck so that he can deliver the animal for further processing at a licensed facility. Last year, he averaged a harvest of nearly one bison per week.

Around 60 percent of the meat Skoglund has processed stays in his community and he’s proud to deliver orders directly to his customers. He says this process builds long-term relationships with his customers that keep his business thriving, and it allows people to ask him questions about his methods, the meat industry, and how to prepare bison.

“Ultimately, it just feels wonderful to meet in person and deliver the meat,” he said. “I always drive away feeling really, really good.”

September 4, 2024

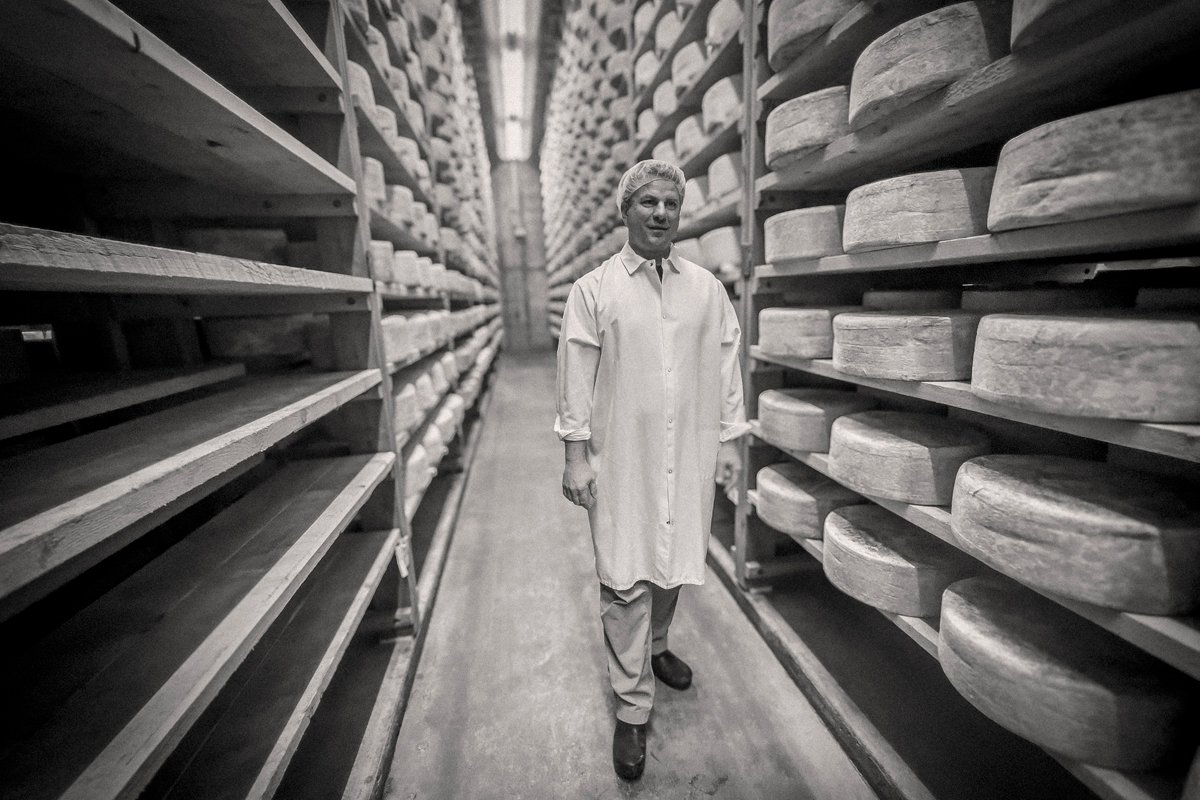

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.