Despite its enormous budget, experts and former service members say the U.S. military is failing to ensure soldiers can feed their families.

Despite its enormous budget, experts and former service members say the U.S. military is failing to ensure soldiers can feed their families.

July 10, 2023

San Diego hosted a food distribution at Pechanga Arena last June. (Photo credit: Victoria Pearce, Feeding San Diego)

Raising four growing boys while serving in the U.S. Army was a daunting assignment for Roteshia Adams, who enlisted in 2007 and rose to the rank of E-4 specialist while stationed at the nation’s largest active-duty armored post in Fort Cavazos, Texas. Her spouse of 14 years, Duvuri Sanders, is also in the Army, and together they have often found it difficult keeping enough food on the table.

“Being dual-military, that was a struggle,” said Adams, who explained their earnings were too much to receive SNAP benefits, but not enough to buy the groceries they needed to feed a family of six.

Adams, who retired from the reserves last year, said each unit had an assigned financial officer that soldiers were able to consult for support whenever they faced nutritional hardships. That person would advise service members to visit their on-base chapel to peruse the food pantry or give them gift cards to use at the commissary. In other words, food insecurity has become a normal part of military life.

The Fort Hood metro, located 60 miles north of Austin, is home to almost 42,000 stationed active-duty service members in addition to more than 48,000 family members who live with them. Sixteen percent of residents inside Fort Cavazos, formerly known as Fort Hood, struggle with poverty and many face food insecurity, but recent inflation has made it worse—in Fort Hood and elsewhere around the nation.

Even the Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA)—the entity in charge of stocking groceries for service members—has seen the impacts of inflation affecting staple foods on military bases and installations scattered across the country.

The military reduced grocery prices at military bases last fall, to an average of 22 percent less than in civilian grocery stores. Bill Moore, director and CEO at DeCA, said the savings for military families should exceed 25 percent for the current fiscal year.

“Part of the challenge is the culture of pride in the military. We made a strategic decision to host the food distribution events off-base to remove as many barriers to entry as humanly possible.”

Despite the cuts, many active-duty service members struggle to feed their families. A recent RAND Corporation report found that more than 15 percent of all active-duty military personnel are food insecure.

Food insecurity is a glaring problem, said Adams, who has been tracking the problem more closely since receiving her recent honorable discharge. She has been helping redress its harms at the Fort Hood Spouses Club, a nonprofit that supports military spouses through community outreach, by organizing monthly food distributions in her own backyard.

“I began to see it more not only in my home, but within our community,” said Adams. “I was listening to my neighbors and the ladies in the spouses’ club. They were forced to stretch meals, get loans, or visit the food pantry. The BAS isn’t enough.”

The Basic Allowance for Subsistence, or BAS, is a tax-free monthly stipend provided by the Department of Defense to offset the cost of meals. The food cost index, published by USDA, is utilized to adjust the BAS benefits annually.

Currently, officers receive $311 to spend on food a month, while enlistees—who receive less pay—get $452 a month. Enlistees didn’t gain full access to the allowance until 2002. Yet the Defense Department still required them to pay for their on-base meals.

BAS has risen by 28 percent in the last decade, but accessing healthy and affordable food is still difficult for soldiers, both financially and socially. And while the House and Senate have been debating the limitations of BAS and other military quality-of-life concerns recently, they have yet to make any significant changes. In the meantime, philanthropic charities have been stepping up to respond to the daily needs of military families.

Fort Cavazos has one of the nation’s highest levels of food insecurity among military service members and their families. Virginia’s Hampton Roads, where the Norfolk Naval Station is located, the U.S. Army’s Fort Liberty in North Carolina, and Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington, are three other notable military communities coping with its crippling effects.

Shannon Razsadin, the wife of an active-duty Navy spouse who sits as one of three civilian advisors to the Military Family Readiness Council for the Secretary of Defense, is also the executive director at the Military Families Advisory Network (MFAN).

She explained that the organization determined through national polling that these are four locations where residents need the most help accessing food. This polling motivated MFAN to respond to this national problem by delivering more than 2 million meals to over 10,000 military families at 18 food distributions since May 2021.

Active-duty service members weren’t the only members of the military community who benefited from their charitable acts. No one was turned away, so veterans and reservists also received support from these disbursements. However, none of their events have ever occurred on military bases.

“Part of the challenge is the culture of pride in the military,” said Razsadin. “We made a strategic decision to host the food distribution events off-base to remove as many barriers to entry as humanly possible.”

Not all nonprofit groups have made that choice. Food distribution events overseen by outside providers are considered non-federal entities, according to U.S. Navy Commander Nicole Schwegman, a Defense Department spokesperson.

Schwegman told Civil Eats that installation commanders may determine whether services provided by organizations like MFAN and Feeding America “conflict with or detract from local DoD programs.” These same commanding officers can ultimately approve or deny access to charitable organizations, including MFAN.

Lack of access to bases is a direct barrier to feeding military families. The events are often out of sight and mind for many active-duty members, ultimately limiting the reach, visibility, and impact of their donations.

“I honestly think that if the installation took on that [on-base] approach, we would see a lot more families not facing food insecurity. We can reach a lot more people,” said Adams. “That could get more people out . . . and the stigma wouldn’t be so much attached to it, because of the camaraderie in the military community, especially amongst spouses.”

An internal survey conducted by Feeding America found that more than a third of its affiliated food banks had a military installation or base located within their service area in 2021.

Vince Hall, the former CEO at Feeding San Diego, said he was surprised by the scale of military food insecurity in Southern California when he started working in that role and began visiting military installations throughout the region.

“It was shocking to me that solving hunger for the families of active-duty military service members was going to be a part of my work,” Hall admitted. “I had no knowledge of the severity of this issue and was embarrassed that our country has stationed so many military families here but is not paying them enough to live in San Diego.”

The Economic Policy Institute (EPI), a nonpartisan nonprofit think tank, reported that the San Diego-Carlsbad metro area ranks 11th for the highest cost of living among the top 100 largest metro areas in the nation.

Hall, who now works as the chief government relations officer at Feeding America, helped steward the founding of Feeding Heroes, a local initiative to assist one of the nation’s largest concentrations of military personnel in San Diego.

An estimated 120,000 active-duty service members call San Diego County their home, a combined figure of 403,000 when including their families. Feeding San Diego distributed more than 3.9 million pounds of food through that program in partnership with 12 nonprofits and four schools located near military installations in 2022.

Housing is another expensive hurdle. Hall said the Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH) isn’t enough for active-duty service members in that housing market, which often forces families to choose between buying food or paying rent.

Although BAH is nontaxable, the benefit is counted against active-duty service members who apply for SNAP, causing many to be denied. Households that received SNAP benefits included 22,000 active-duty service members in 2019 alone.

“It’s a complex issue and we understand that, but we also believe that families should not be in a situation where they are struggling with this very basic need,” said MFAN’s Razsadin. “Removing the Basic Allowance for Housing from that equation would be a huge step in the right direction.”

Charitable entities like Feeding America and MFAN are aiding military families and filling a much-needed gap in real time, but their leaders realize that their resources are strained and finite.

“It’s not a sustainable model. We can’t host a food distribution event every day,” said Razsadin. “Policy-related changes are going to be required to fix this issue, but military families do not have the luxury of waiting.”

Hall said the military’s decision for MFAN to operate food assistance services off-base is ultimately an optics issue for the Defense Department, as high-level Pentagon officials are “not wanting to have this issue see the light of day.”

“One of the biggest barriers for military families is the desire to never embarrass the chain of command, and to avoid any stigma associated with seeking assistance,” Hall added.

Beth Asch, the lead author of the RAND report commissioned by the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act, agreed. “The culture is not conducive to saying, ‘I need help,’” she said. Her team’s research found that early- to mid-career active-duty enlisted personnel are the most susceptible to food insecurity. Single military parents with children as well as racial and ethnic minorities are also more likely to struggle.

“One of the biggest barriers for military families is the desire to never embarrass the chain of command, and to avoid any stigma associated with seeking assistance.”

These families face unique challenges that put them at greater risk of periodically lapsing in and out of food insecurity. While most military families move every two and three years, more than 400,000 service members undergo a permanent change of station (PCS) annually. MFAN once estimated that families spend an average of $1,913 in unreimbursed out-of-pocket expenses each time they move.

Caitlin Welsh, director of the Global Food Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), said civilian spouses often forfeit their jobs during these demanding moves. A loss of secondary income further intensifies financial hardship, thus raising the risk of food insecurity.

“Military families experience a lot of the same challenges that all families experience,” said Razsadin, “but there are nuances that make it a little bit harder.”

A staggering 26 percent wage gap between military spouses and their civilian counterparts intensifies financial inequities and is often the result of frequent relocations.

That disparity in wage potential among military spouses is expected to rise to 38 percent due to the pandemic, according to a survey conducted by Hiring Our Heroes in collaboration with Syracuse University’s D’Aniello Institute for Veterans and Military Families.

Blue Star Families estimated that unemployment, underemployment, and reduced labor force participation among military spouses cost the U.S. economy nearly $1 billion annually. An absence of affordable childcare creates additional constraints for many families.

“Those moves are definitely hard on families,” said Adams. “Childcare, spousal employment, all of it plays into that pot of food insecurity.”

On top of that, promotions pave the path for enlistees to earn more, but those with unpaid debt and other personal finance challenges have difficulty gaining the national security clearances that correspond with raises.

The Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency, which approves national security clearances for civilian and military personnel, has denied or revoked at least 745 clearances so far during the 2023 fiscal year. Nearly 90 percent were cited due to financial considerations, according to Cindy McGovern, deputy of DCSA’s Office of Communications and Congressional Affairs.

“A soldier who doesn’t know how to manage their budget is a liability, and [that] can be used to penalize you,” said Josh Protas, vice president of public policy at MAZON, a Jewish faith-based anti-hunger nonprofit. “There’s a paternalistic aspect that I think adds to that level of shame and embarrassment.”

“Part of the issue is that people cycle in and out of it. They have a sudden medical expense or a car repair that throws their world upside down,” Protas added. “Well, you don’t expect them to sell all of their kids’ toys to put food on the table.”

He sees the military stigma against families struggling to make ends meet as “the military version of the ‘welfare queen’ [stereotype],” which is essentially “blaming the individuals for the situation that they’re in.”

Protas added that those who attempt to ask for help face the fear of retaliation by intrusive commanding officers. Often, that means simply being overlooked for a promotion.

The Defense Department declined to comment on perceived attitudes toward food-insecure service members who ask for support, but advised those who may feel targeted to file an official complaint.

“I want to make clear that taking care of our people is a top priority for the Department, and we continue to focus and look [at] ways to take even better care of our service members and their families,” Schwegan told Civil Eats in a statement.

Hall added that “pointing a finger of blame at service members and accusing them of a lack of financial competency is deeply hurtful.”

These problems come at a time when the number of Americans enlisting for the all-volunteer force, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, is at an all-time low. And experts said that increasing access to SNAP on top of BAS would help military families lead happier and healthier lives—and make them more prepared to serve their country—but that won’t do it alone.

“Fixing other challenges across military life could also have benefits for food security, and they should be recognized as such,” said Welsh. However, unlike SNAP, which is shaped by the farm bill, military quality-of-life issues fall to the Defense Department. As a result, members of Congress have looked to the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) to address the active-duty food insecurity dilemma in the armed forces.

House Democrats from the Armed Services and Agriculture committees sent Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin a letter last March, urging him to ensure that the Basic Needs Allowance is “as effective as possible in combatting food and financial insecurity for low-income servicemembers.”

One of their recommendations includes creating an exemption for the Basic Allowance for Housing stipend when determining eligibility for the Basic Needs Allowance. This policy provision failed to gain momentum in the previous NDAA.

Representative Jim Costa, a Democrat from California whose district encompasses the city of Fresno and surrounding communities outside of Modesto and San Jose, was among the letter’s authors. He told Civil Eats that those “conversations have continued.”

“This should be a team sport, an American endeavor to work for and support our military. It’s unacceptable, and we’re gonna fix it.”

“I can’t tell you that we have a consensus,” said Costa. “At the end of the day, I think we have to have a meeting of the minds, as to where the deficiencies are and how we address those—whether it’s in the farm bill or some other vehicle.”

Democrats hope to expand SNAP funding across the board in what could be the first trillion-dollar farm bill in U.S. history, but increasing food stamp benefits for junior enlistees is “just gonna put a Band-Aid on the problem,” said Representative Don Bacon (R-Nebraska), who served as the former ranking member for the nutrition subcommittee.

“I don’t think there’s a Republican that would say they could live with the fact that a junior enlistee is on SNAP right now,” added Bacon. “This should be a team sport, an American endeavor to work for and support our military. It’s unacceptable, and we’re gonna fix it.”

Last week, members of the Republican-led House Armed Services Committee, including Bacon, brought renewed attention to the issue after passing a proposed budget for the 2024 fiscal year that removes the Basic Allowance for Housing from the Basic Needs Allowance eligibility.

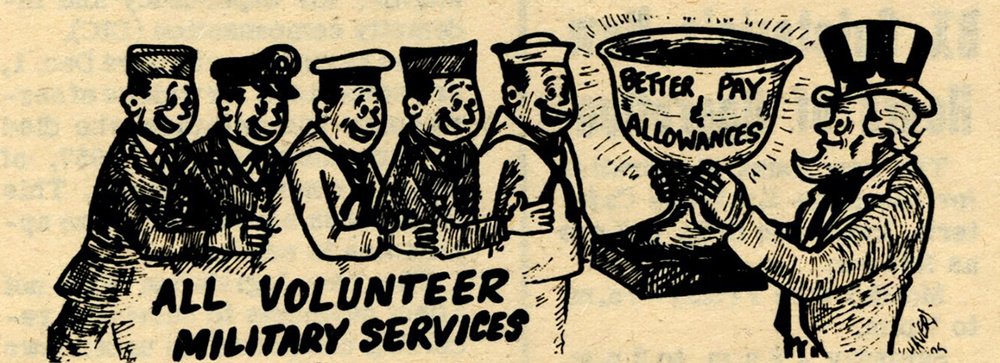

A 1969 cartoon appearing in the “Bolling Beam” military newspaper at the Bolling Air Force Base, in Washington, D.C., brings attention to the prospects of an all-volunteer force and the possible benefits that come with it. (Illustration courtesy of the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service)

“Now it is critical that the Senate Armed Services Committee to follow this lead and take action to eliminate the barrier that prevents the vast majority of military families struggling with food insecurity from qualifying for the Basic Needs Allowance,” said Protas at MAZON.

Earlier this year, Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-Illinois) reintroduced the bipartisan Military Family Nutrition Access Act, a bill designed to exclude military housing allowances from income when determining SNAP eligibility. She hopes to get this piece of legislation added to the upcoming farm bill.

“As someone whose family relied on these nutrition programs after my father lost his job, and who served in the uniform for most of my adult life, I’m proud I reintroduced this bipartisan legislation,” Duckworth told Civil Eats in a statement.

Republicans like Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Glenn “GT” Thompson (R-Pennsylvania), chairman of the House Agriculture Committee, also told Civil Eats that they believe the Basic Housing Allowance should not count towards SNAP.

Service members are supposed to “get housing, three squares, and what they need,” Thompson said, while speaking about his son, who served in Afghanistan alongside many troopers that struggled with food insecurity. “I do believe wholeheartedly that the way to do that is to not count basic housing allowances. Let’s get it done whenever we can.”

Increasing salaries for junior- and mid-enlisted service members has been another top priority among Republicans who now control the House chamber. The military personnel subcommittee has created a new special panel that will be chaired by Bacon later this summer and aim to explore possible policy remedies, including pay raises.

“In order for the military to be successful, we’re going to have to help them make a living wage and take care of their families,” Senator John Boozman (R-Arkansas) told Civil Eats. “If not, then recruiting is going to be even more difficult than it is now.”

Protas called pay raises the “ultimate solution” but acknowledged that they may not be politically feasible. “Even if you were to do it in a targeted way just for junior enlistees, there's still a big price tag on that,” he said.

Republicans sitting on the House Armed Services Committee also proposed to increase the paychecks of all service members by 5.2 percent.

For Roteshia Adams and her husband, a pay raise would have made a big difference while they were raising their children, who are now but all grown up. But it can still make a difference for many. Feeding America’s Hall said it’s clear that something has to change for the sake of service members and their families, now and in generations to come.

“A portion of their mental energy is devoted to wondering if their kids back in Norfolk or San Diego have enough to eat that day,” said Hall. “When we put people in harm’s way, we want to give them all of the resources they need to focus on the job and not have to worry about the security of their families.”

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

August 12, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.