Most American farms consume massive amounts of oil and gas. As the climate crisis intensifies, lawmakers must start regulating the industry and holding it accountable for its impact on the air and water.

Most American farms consume massive amounts of oil and gas. As the climate crisis intensifies, lawmakers must start regulating the industry and holding it accountable for its impact on the air and water.

September 14, 2023

Most of America’s farms are dependent on prodigious amounts of fossil fuels at every stage of production. Powerful PR firms have worked overtime in recent years to craft a narrative that highlight farms’ potential role in mitigating climate change, but the truth is that agriculture consumes 6 percent of the world’s fossil fuel energy, and the oil and gas industries rely on industrial agriculture for one of its largest and most lucrative markets.

From planting to harvest, farm machinery such as tractors and combines burn diesel fuel to churn out the raw materials for our food system. The freight trucks, locomotives, and inland barges that transport bulk harvested commodity crops and livestock significantly add to agriculture’s CO2 emissions. Because farm machinery is often built to last, progress to electrify those vehicles is slow even though it holds huge untapped potential to reduce agriculture’s emissions.

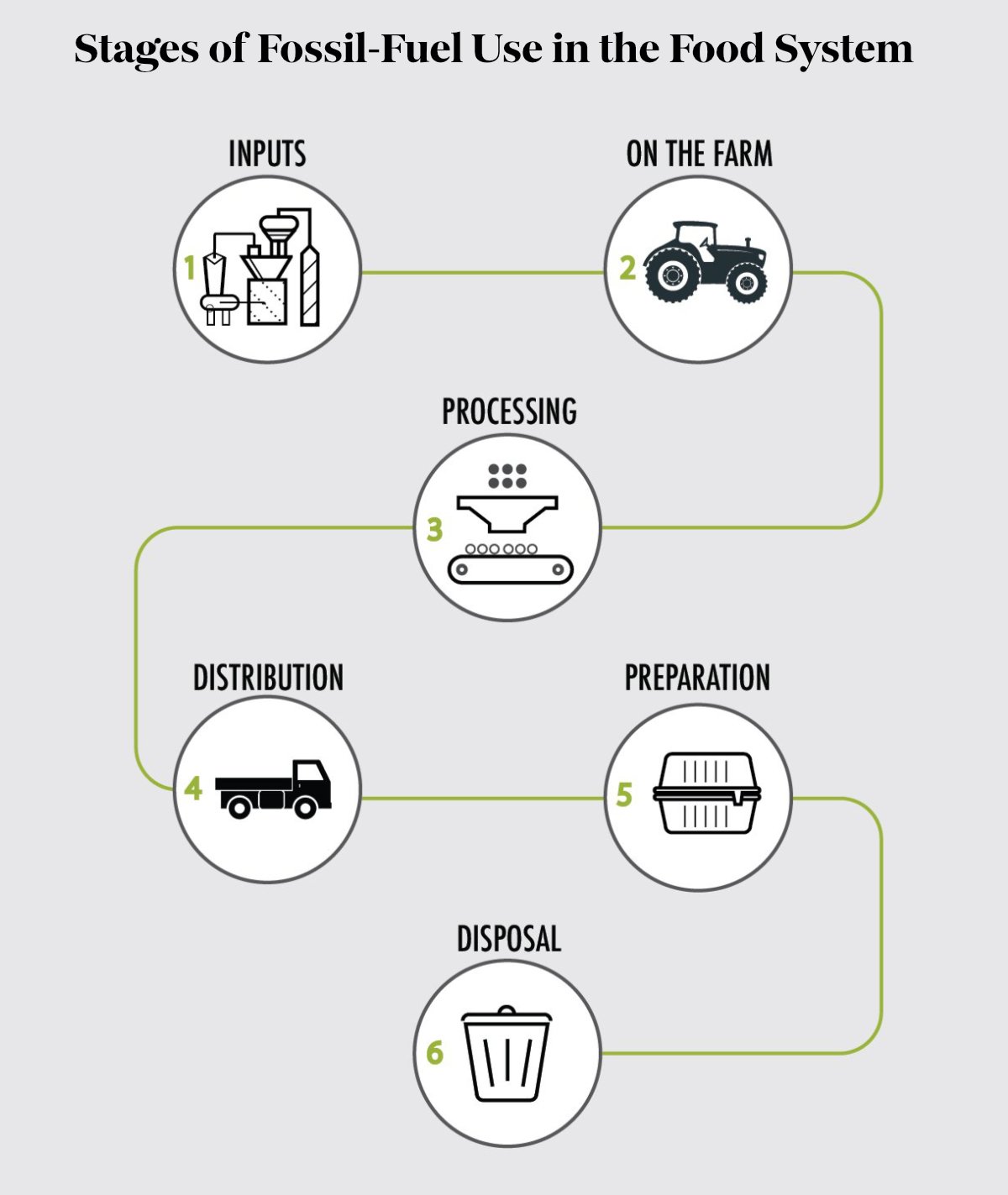

(1) Agrochemical production consumes fossil fuels to generate pesticides, fertilizers, and other inputs. Approximately 3–5 percent of the world’s fossil gas production is used for synthesizing ammonia. (2) On croplands and grazing lands and at industrial farming operations, equipment used to clear and prepare land, produce crops and house, feed and slaughter animals rely on fossil fuel inputs. (3) The use of fossil fuels to produce the foods and beverages consumed by Americans in 2007 accounted for about 14 percent of economywide CO2 emissions from fossil fuels. (4) Transport accounts for about 19% of total food-system emissions. (5) Food preparation and plastic packaging relies on fossil fuels and petrochemicals. (6) Finally, food waste processing can result in additional fossil fuel use.

On-farm activities like irrigation rigs also require a lot of generated power. At large livestock facilities specifically, the lighting, cooling, heating, and pumping of water and waste consume a huge amount of electricity. Eventually, agriculture’s electrical use could become a climate bright spot through the widespread adoption of truly renewable sources like wind and solar. But rural America still relies on electrical co-ops, which depend mostly on fossil fuels. (There is some hope for change, though. The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act directed $9.7 billion to electric cooperatives to transition to renewables.)

“In 2016, a third of America’s 1,500 farming co-ops sold $17 billion in diesel and other petroleum products.”

In addition, pesticides and fertilizers are derived from fossil fuels. American agriculture is awash in a mix of both, as farms use about a billion pounds of pesticides and 21 million tons of synthetic fertilizer every year. The fossil fuel industry views these as the uses with greatest potential for petrochemical growth. Since 1960, global value of pesticide exports has increased 15,000 percent while synthetic fertilizer use has increased ninefold.

These pesticides and fertilizers are harmful to both human health and the climate. For example, chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxic pesticide in the organophosphates class of chemicals that were first developed by the Nazis for chemical warfare, is acutely toxic. Although the EPA has banned the use of chlorpyrifos in food, it is still widely used in U.S. agriculture on cotton, corn used for ethanol, Christmas trees, and golf courses despite the fact that is associated with neurodevelopmental harms in children.

Nitrate fertilizer, which is widely used on conventional farms, is made with huge amounts of methane gas. In fact, the gas industry and the American Legislative Exchange Council (a far-right “limited government” legislative policy group) boast that agriculture is dependent on fossil fuel gas. The gas industry points out that 30 percent of all global energy is used for food production and distribution, while agriculture consumes almost 15 percent of U.S. commercial and industrial fossil fuel gas. Fertilizer production accounts for about a third of the total energy used in crop production.

Agriculture’s willful dependence on fossil fuels is not entirely surprising. While it’s important to have a food safety net, the government subsidized crop insurance program and regular federal disaster payments insulate producers from risk and create few incentives to employ practices that regenerate the soil and hold more moisture and organic matter in the ground in a way that minimizes climate risk. Instead, most producers pour on more (subsidized) fossil fuels.

Although they receive subsidies for using fossil fuels and face an onslaught of climate disasters—from drought to floods to intense heat waves—many commodity farmers are still skeptical of the proven science behind global warming. For instance, an Iowa State University survey found that in 2020 a scant 18 percent of farmers in the agriculture bellwether state believed human activity was mostly responsible for climate change.

“As the climate crisis intensifies, it’s time to see agriculture for what it is: an industry that produces needed goods and requires oversight.”

Much of farmers’ climate skepticism can be traced to the largest and most powerful agriculture trade group in the country, the American Farm Bureau Federation. The Farm Bureau has long been close allies of the fossil fuel industry and fights all climate legislation that might slow fossil fuel use. The Farm Bureau also enjoys considerable financial rewards from fossil fuels.

Farm Bureau Oil Company was formed in 1930 and grew to own 1,200 oil wells, a pipeline network, and refineries by the 1960s. In 2016, a third of America’s 1,500 farming co-ops sold $17 billion in diesel and other petroleum products. Closer to agrochemical companies than actual farmers, the Farm Bureau has long promoted policies aimed at codifying an industrial agriculture system dominated by fossil fuel dependent megafarms.

As the climate crisis intensifies, it’s time to see agriculture for what it is: an industry that, like many others, produces needed goods and requires oversight. As the first step, we must put an end to the many exemptions in the laws regulating industrial agriculture’s impacts on our air and water.

Legislators and the public recognize that the fossil fuel industry cannot be left to its own devices and they have imposed strict air and water pollution limits. Lawmakers must do the same for industrial agriculture. Moreover, in the 2023 Farm Bill, legislators must support and drive transformative change toward climate-friendly practices and products.

September 4, 2024

By paying top dollar for milk and sourcing within 15 miles of its creamery, Jasper Hill supports an entire community.

September 3, 2024

August 27, 2024

August 26, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.